Members of elite unit gather to discuss Ashley’s War

By Jim Moriarty

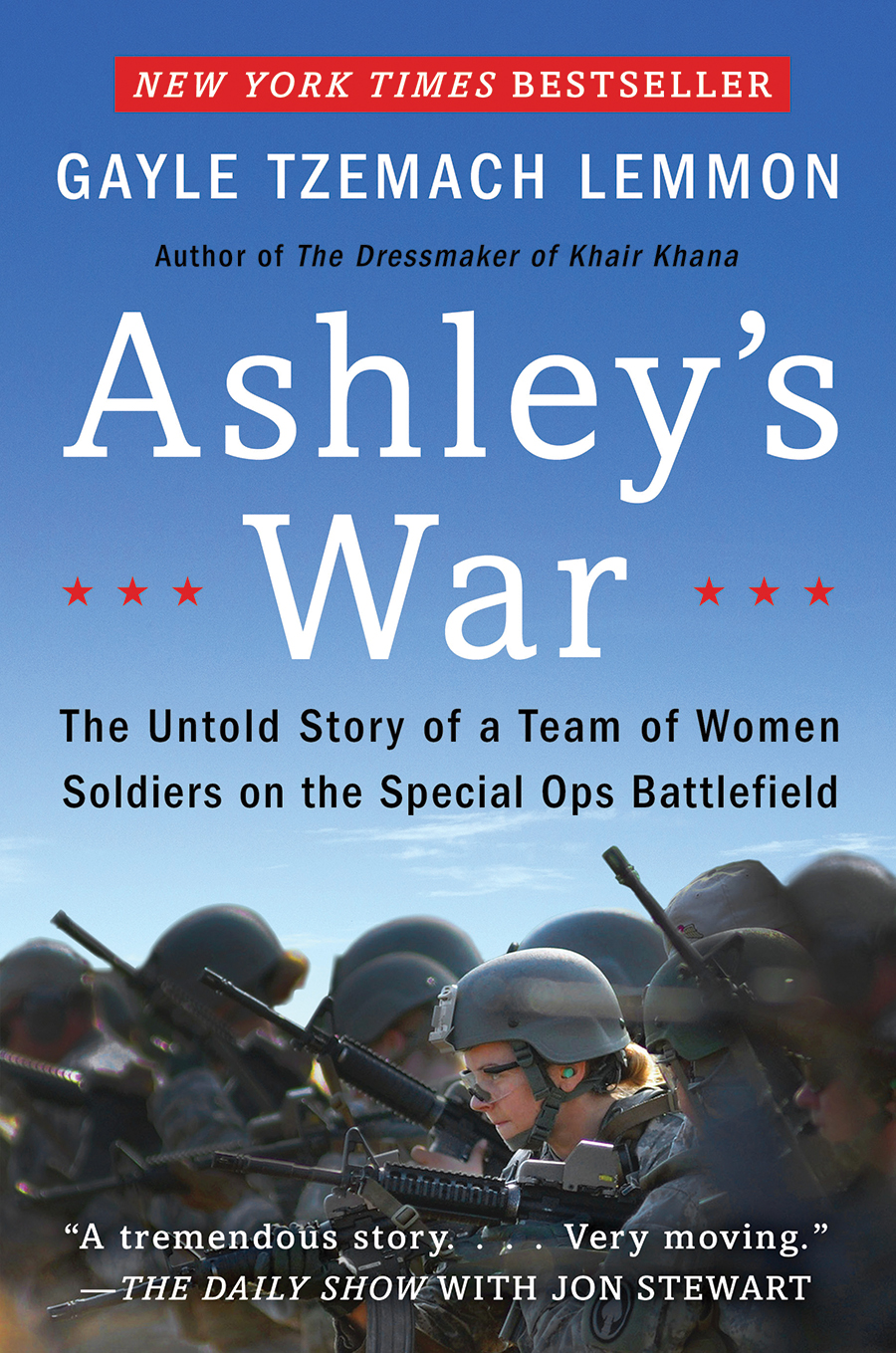

Ashley White was a first lieutenant assigned to the 230th Brigade Support Battalion, 30th Heavy Brigade Combat Team attached to the Joint Special Operations Task Force when she was killed in action in 2011 in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. She was a member of a Cultural Support Team, a very special unit composed of very special women.

The CSTs, as they are called, undertook night missions with elite Army Rangers. Their job was to interact with women and children in countries like Afghanistan where contact between women and men they’re not related to is socially unacceptable. When the Rangers entered a compound in search of insurgents, the CST officers would calm the women and children, search them for possible weapons or explosives (and to see if a man was hiding dressed as a woman) and, finally, obtain whatever intelligence they could. It was dangerous work in a dangerous part of the world.

On Thursday, March 19, Amy Sexauer, Shelane Etchison and Caroline Cleveland, three women who trained and served with Ashley White, will lead a panel discussion of Ashley’s War, a New York Times best-seller by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon. All three appeared in the book under aliases. The event — “Ashley’s War: Bonds of Women in Combat” — will be held at the Country Club of North Carolina. Doors and a cash bar open at 6:30 p.m., and the program begins at 7 p.m. Tickets are $35 and available at ticketmesandhills.com. All proceeds benefit 2020 Women Build, a committee for Habitat for Humanity of the N.C. Sandhills. (Film rights for Ashley’s War were acquired by Fox 2000 and Reese Witherspoon, and the project is in development.)

“Stepping back and looking at things from a larger picture, Ashley’s War and the story of CST is the story of a collective group of women rising to a challenge and finding deep friendships along the way,” says Etchison, who is out of the Army pursuing dual advanced degrees at Harvard University, one in business and the other at the Kennedy School of Government. “You hear about the brotherhood all the time. You never really hear about the sisterhood.”

In 2013, 1st Lt. Jennifer Moreno became the second CST killed in combat. Trained originally as a nurse, Moreno was killed when she rushed to the aid of a fallen comrade. She was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star for bravery. “My first priority is to memorialize the legacy of Ashley White and Jenny Moreno, who are the first and hopefully only CSTs to be killed in action,” says Cleveland, who lives in Fayetteville and is a doctor of physical therapy at Cape Fear Hospital.

“A lot of people have given their life in the military, and not everybody has a book written about them,” says Sexauer, who lives in Southern Pines, as have many of the CSTs. “It’s an honor to be able to carry on Ashley’s legacy. It’s not always easy, it’s not always comfortable, to talk about the past and about the things we did in the military, but it’s an honor to keep Ashley’s legacy alive.”

The following is an excerpt from the preface of Ashley’s War, edited for space:

Second Lieutenant White entered the “ready room” and began preparing for the night of battle.

White felt the fear rising, but more seasoned soldiers had provided plenty of advice for the special brand of trepidation that accompanies a soldier on their first night mission. “It gets easier after the first time,” they assured the newbies during training. “Don’t indulge it, just pass through it.”

Ready now, White stepped into the briefing room and took in the scene. Dozens of battle-hardened men from one of the Army’s fittest and finest teams, the elite special operations 75th Ranger Regiment, crowded in to watch a PowerPoint presentation in a large conference room. Many had Purple Hearts and deployments that reached into the double digits. Around them was the staff that supports soldiers in the field with intelligence, communications, and explosives disposal capabilities. Everyone was studying a diagram of the target compound as the commanders ticked through the mission plan in their own vernacular, a mix of Army shorthand and abbreviations that, to the uninitiated, sounded like a foreign language.

White had the feeling of being in a Hollywood war movie. Standing nearby was a noncommissioned officer (NCO) and Iraq War veteran whom the second lieutenant had trained with.

“Are we supposed to say something?” White asked.

Staff Sergeant Mason, also out for the first time, scooted closer and whispered back. Neither new arrival wanted to stand out any more than they already did.

“No, I don’t think so, not tonight. The last group will speak for us.”

That was a relief. White had no desire to draw attention in a room filled with soldiers who clearly felt at home in combat. Like a cast of actors who had performed the same play for a decade, they knew each other’s lines and moves, and offstage they knew each other’s backstories. It was an unexpected revelation for White, gleaned during a fifteen-minute mission review in a makeshift conference room in the middle of one of Afghanistan’s most dangerous provinces: this was a family unit. A brotherhood.

The briefing ended, the commanding officer approached the front of the room and the soldiers suddenly shouted as one:

“Rangers Lead the Way!”

In one of the many Velcroed pockets of White’s uniform was information about the insurgent they were after and a list of crimes he was suspected of committing. In another pocket was a medal of St. Joseph and a prayer card. White stepped out of the barracks and worked to conceal any trace of the intense emotions this moment conjured up: pride in being part of a team hunting a terrorist who was killing American soldiers and his own countrymen; trepidation at the thought that after a short ride on the bird they would all end up in his living room. But it was exactly what White had wanted and trained for: to serve with fellow soldiers in this long war and do something that mattered.

The fighters lined up by last name and marched into the yawning darkness of the Kandahar night. Unlike the American cities they came from, whose skies were often clouded by the pollution of industry, traffic, and the millions of lights that power a modern, twenty-four-hour-a-day society, Kandahar’s blackness stretched on forever with constellations you only read about at home. But then a powerful stench yanked the young officer back into the moment. As heavenly as the skies were, just so earthly was the smell of human excrement that hovered over and seemed to surround the Kandahar camp. In a city whose sewage system had been all but destroyed by war, the smell of feces attacked with ferocity anytime a soldier was downwind.

But White was focused on something even more mundane: staying upright while marching along the unpaved, rock-strewn tarmac for the first time in total darkness. “Focus on the next step,” White silently commanded. “No mistakes. Do your job. Don’t mess up.”

White and Mason fell in alongside their fellow special operations “enablers,” a group that included the explosive ordnance disposal guys who became famous in the Hollywood blockbuster The Hurt Locker. Close behind was their interpreter, an Afghan-American now entering year four in Afghanistan. Language expertise notwithstanding, the interpreter’s gear looked like it came from the Eisenhower era. They all guessed some soldier had worn that helmet back in Vietnam; it barely held the clips for night-vision goggles and was seriously dinged.

Entering the cramped helicopter, White and Mason were determined not to make a beginner mistake by taking the wrong seat, so they fell in behind a first sergeant, who had taken the new arrivals under his wing. After he sat, they followed his example, snapping a bungee cord that hung from a metal hook on their belt into hooks beneath a narrow metal bench. In theory, these cords would keep them from flying across — or out of — the helicopter while it was airborne. The soldiers took root, and with a sudden whirr the bird was off.

Here we go, White thought. Outwardly the picture of calm, inside the young officer felt a rush of adrenaline and fear. Everything — the selection process, the training, the deployment — had happened so quickly. Now, suddenly, it was real. For the next nine months this is what every night would look like.

Over the booming engine noise the first sergeant barked out the time stamp in hand signals.

“Six minutes.”

“Three minutes.”

White turned to Mason and gave the thumbs-up with a smile that was full of unfelt confidence.

“One minute.”

Showtime.

The bird landed and the door flew open, like the maw of some huge, wild reptile that had descended from the sky. White followed the others and ran a short distance before taking a knee, managing to avoid the worst of the brownout, that swirling mix of dust, stones, and God-only-knows what else that flies upward in the wake of a departing helicopter.

With barely a word exchanged, the Rangers fell in line and began marching toward the target compound.

The ground crunched beneath their feet as they pressed forward through vineyards and wadis, southern Afghanistan’s ubiquitous ditches and dry riverbeds. They marched quickly, and even though the night goggles made depth perception a nearly impossible challenge, White managed not to trip over the many vines that snaked along and across the rutted landscape. No one made a sound. Even a muffled cough could ricochet across the silence and bring unwanted noise into the operation.

Fifteen minutes on they reached their objective, though to White it felt like only a minute had passed. An interpreter’s voice could be heard addressing the men of the house in Pashto, urging them to come outside. A few minutes later the American and Afghan soldiers entered the compound to search for the insurgent and any explosives or weapons he might have hidden inside.

And then Second Lieutenant Ashley White heard the summons that had led her from the warmth of her North Carolina home to one of the world’s most remote — and dangerous — pockets.

“CST, get up here,” called a voice on the radio.

The Rangers were ready for White and her team to get to work. The trio of female soldiers — White, Mason, and their civilian interpreter, Nadia — strode toward the compound that was bathed in the green haze of their goggles. It was dead in the middle of the night, but for White, the day was just beginning.

Her war story had just begun. It was time for the women to go to work. PS