Classic lamps on display at Reynolda House

By Jim Moriarty

Due to health precautions related to COVID-19, the Reynolda House Museum of American Art closed temporarily in March and the opening of “Tiffany Glass: Painting with Color and Light” was delayed. For information regarding the reopening of the museum and its exhibits please visit www.reynoldahouse.org.

While on one hand it could seem as though Louis Comfort Tiffany was born with a silver glasscutter in his mouth, the son of the founder of Tiffany and Company created, over his lifetime, an entire genre of decorative art so ubiquitous, so singularly chic and stylistically distinctive that his name alone has come to represent the thing itself. It is the de rigueur description of any leaded glass shade. Say “Tiffany lamp” and you need say no more. All the rage one day, passé the next, fashion may be fickle, but the art endures.

The intimate gallery space at the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem will house an exhibit of Tiffany’s finest work on loan from the Neustadt Collection at the Queens Museum in New York. The traveling exhibition was to open in late March and continue through June 21 before it was overtaken by events.

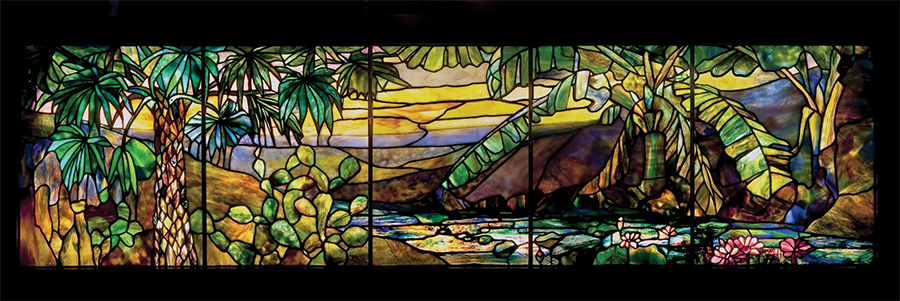

“The decorative arts are accessible to everybody,” says Phil Archer, Reynolda’s director of Program and Interpretation. “To have a gallery with the light actually shining through the works of art will be new for us and make it a very magical space. It just fits at Reynolda because of the natural setting of the gardens. We wanted the exhibition in the spring for that reason. Come and see all the flowers, then come inside and see all the flowers.”

The show, when it’s able to open, will be comprised of 20 of the most celebrated examples of Tiffany’s lamps and, interestingly, three forgeries that serve to demonstrate the difference between faux Tiffany and authentic works. There will be a display demonstrating the steps in the creation of the lampshades and biographical information on the key personnel at Tiffany Studios — chemist Arthur J. Nash and designers Clara Driscoll, Agnes Northrop and Frederick Wilson — who all made meaningful contributions to the artistry of the lamps.

Also part of the exhibit are five Tiffany windows and, separate from the exhibit, a display of Tiffany vases purchased by Katharine Reynolds on view in the Reynolda House itself.

The role of Driscoll, née Clara Wolcott, who was in charge of the “Tiffany Girls” in the glass cutting department and is responsible for the design of two of Tiffany’s most remarkable lamps, Wisteria and Dragonfly, only came to light in the first decade of the 21st century when Martin Eidelberg, an art history professor from Rutgers University, discovered her letters archived at Kent State University.

“She was an Ohioan, so her papers ended up at Kent State,” says Archer of the letters Driscoll sent home from New York. “The family evidently had almost a chain letter system where Mom would send a letter to Clara, she would send it to her sister who would send it to the brother and they would all add to it. It was better than group texting.”

While Tiffany may not have been solely responsible for every design, “The concepts were Tiffany’s,” says Archer. “The aesthetic was Tiffany’s. The kind of color palette and the combination of colors and details and opacities were Tiffany’s. It’s almost like Mozart writing a piece and then conducting the orchestra. He’s not playing any of the instruments. Everybody else is making the music but the original concept is his. They bring a lot of creativity to how they play it — though that may not be an exact metaphor because some of the concepts, like the Wisteria lamp, were Driscoll’s.”

Born in 1848, the slight, delicate son of Charles Louis Tiffany could have slid seamlessly into the family business. “He had every opportunity to take over from his father and be the lead jeweler and luxury goods maker in New York,” says Archer. “The primrose path was laid out for him.”

When the younger Tiffany was enrolled at Eagleswood Military Academy in New Jersey, he met and studied under the painter George Inness. The effects would be profound. By the age of 19, he had become a founding member of the American Society of Painters in Water Colors and had begun to exhibit his work at the National Academy of Design. He traveled to Europe and North Africa and would be particularly influenced by what, at the time, was called the “Orientalist” style.

“When I first had a chance to travel in the East and to paint where the people and the buildings are clad in beautiful hues, the pre-eminence of color in the world was brought forcibly to my attention,” Tiffany said later. One of his better-known paintings, Snake Charmer at Tangier, Africa, expressed Tiffany’s interest in the play of light and color. It was exhibited at Snedecor’s Gallery in New York in 1872 and later at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. It remained in Tiffany’s personal collection until 1921, when he donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While still painting, Tiffany drifted into design and decorating. At the same time, he had become enthralled by the possibilities of glass as an art form.

“Tiffany hated modern glass because it was too clean,” says Archer. “He wanted glass like archeologists were digging up in Syria and Lebanon. It was like opals. It had color and shimmer. He hired chemists to really develop all of these different colors and ranges. The beauty that he found in that glass and trying to replicate it becomes the story.”

Tiffany didn’t paint on glass — “staining” it only rarely, usually in faces — he painted with glass. The use of metallic oxides allowed for the development of the range of colors that distinguish his work.

“Standing by the glass workers, he had them fold the glass on itself and pinch in places to achieve the effect of magnolia blooms in a window of his library at the Tiffany Mansion,” writes Julia Tiffany Hoffman, a great-granddaughter. “A pulled rod of glass was slightly melted and scrolled on the glass to effect vines, stems and spiderwebs. Louis used just the right color combination of paper-thin glass bits to achieve a painterly quality . . . Molten glass was pressed thin and then stretched to effect the impression of light shining on snow. When working on a window, he would have his glass house make sheets of glass that had several colors running through them, then find the perfect area and orientation to express the petal of a tulip or the leaf.”

In addition to the inspired glassmaking, the creation of Tiffany’s lamps was aided by the innovative use of copper foil. “Instead of having heavy lead connectors,” says Archer, “they were able to use much, much finer connectors. There’s a lot of artistry in the creation of the glass, and there’s artistry in the cutting and piecing it together.”

Tiffany was also receiving commissions decorating American palaces for Gilded Age royalty like Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Henry and Louisine Havemeyer. He decorated Mark Twain’s house in Connecticut and the interior of the old Lyceum Theatre on Park Avenue South in New York. He collaborated with the famous — and infamous — architect Stanford White on a house for the Tiffany family. He did the Ponce de Léon Hotel in St. Augustine, Florida, and Chester A. Arthur’s White House.

“Tiffany would design from soup spoon to chandelier,” says Archer. “He was creating almost complete works of art in these houses. But upper middle-class people could afford the lamps. They ended up propelling Tiffany Studios financially. In his lectures, Tiffany almost never referred to his lamps. He would talk about these huge projects and the large windows. The lamps were sort of the bread and butter.”

Tiffany believed nature should be the primary source of design. “Every really great structure is simple in its lines — as in Nature — every great scheme of decoration thrusts no one note upon the eye,” he wrote. Having outlived two wives and three of his eight children, in his final years Tiffany’s ultimate project was his estate on Oyster Bay on Long Island — Laurelton Hall, 84 rooms on 600 acres. He designed every nook, cranny and garden.

Punctuality and orderliness were valued traits. He owned seven white linen suits, one for each day of the week. A tennis player and avid photographer who never saw a speed limit he wanted to obey, the giant of Art Nouveau attempted to stick his finger in the dike of modernism with the establishment of the Tiffany Foundation, devoted to helping aspiring artists.

“Paintings should not hurt the eyes,” he cautioned them. By the time Tiffany died in 1933, much of his wealth had evaporated in the crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. Laurelton was sold in 1945, and the land subdivided.

In 1957, the largely abandoned great house, containing some of Tiffany’s finest windows, burned to the ground. It took two days to melt the art of a lifetime. PS