A lost son, a missing mother and how their wish of finding each other came true

By Jim Moriarty

“Did you look for me at 23andMe?”

Click. That’s all there was. The voice was uncertain, the accent German. John Gessner had just finished a photo assignment. A beautiful house, a farm, some dogs. Pictures of a good life. He sat in his car and listened on his cellphone. Then he listened again. It was the voice of someone he’d been looking for almost from the day he learned she existed. It took 15 minutes to hit a call back button, compressing 55 years into the first words a mother and son ever shared. And they talked. And they talked. And the years melted away.

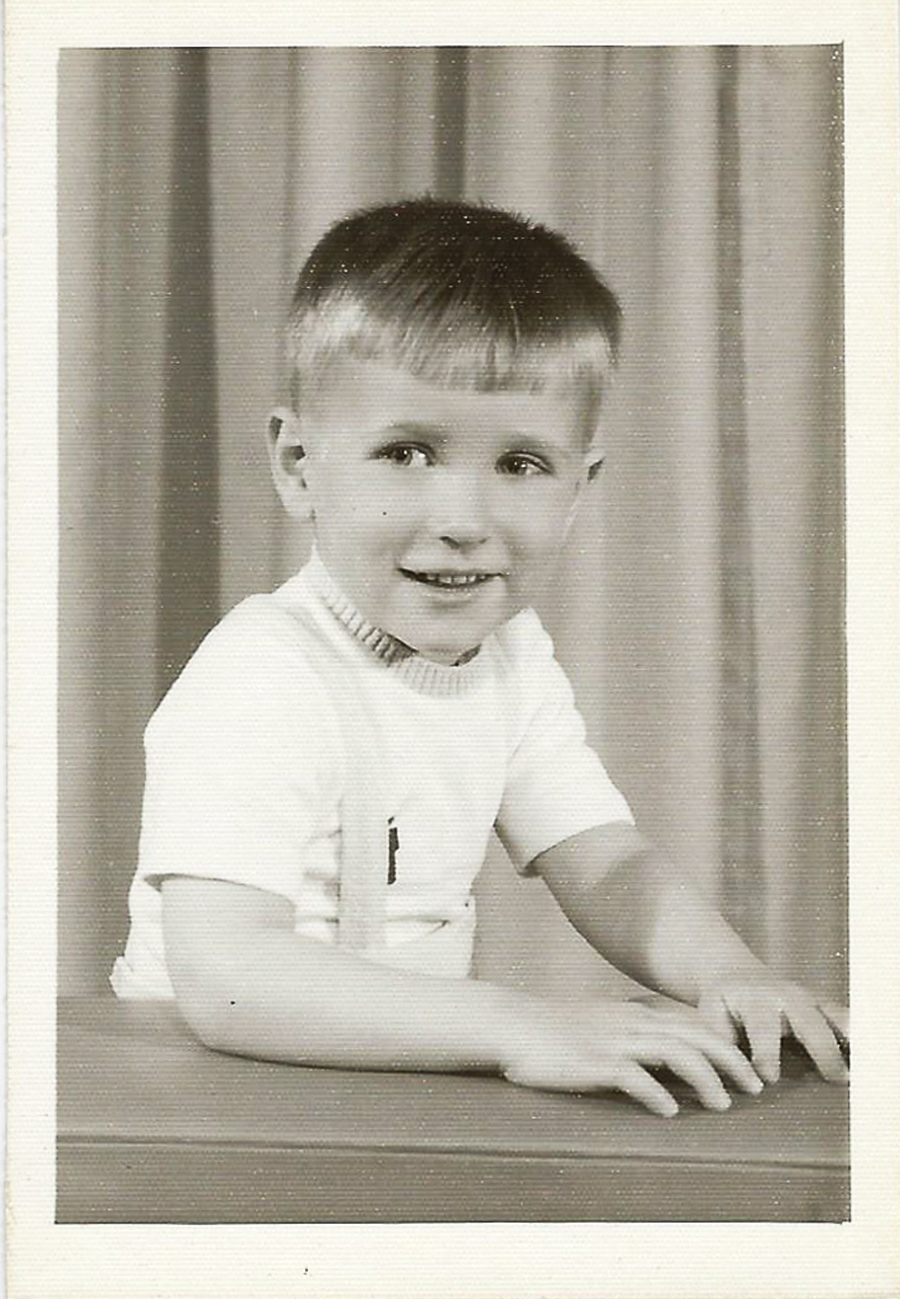

Gessner was born on the last day of January in 1963 at Misericordia Hospital in the Bronx, New York. After shuttling through a series of families, he was adopted before his second birthday by Fred and Stella Gessner. When he was 10, his adopted mother was diagnosed with cancer. The prognosis was dire.

He learned he was adopted when one of his aunts showed him the family Bible. “I started thinking about her,” he says of his birth mother, “kind of like an escape hatch, almost. Self-preservation. When you’re 10 you need a mother. Well, there’s this other person out there.”

As it turns out, Stella Gessner lived for another 10 years, a few months longer, in fact, than her husband. John’s adopted father was killed in a car accident by a drunk driver when John was 20.

“Back in ’94 after my mother died, I wrote to the adoption agency,” Gessner says. The agency was the Catholic Home Bureau, and the details it supplied about his birth mother were opaque, at best. “In New York all the records are sealed. They gave me this non-identifying information which basically said she was from Germany, here on a work visa, and she had no means to take care of me. I signed up (with the agency) that if she ever contacted them and said she was looking for me, then they’d connect us.”

Gessner consulted lawyers, too. “They said it’s incredibly expensive and there’s no guarantee.” It seemed like a dead end.

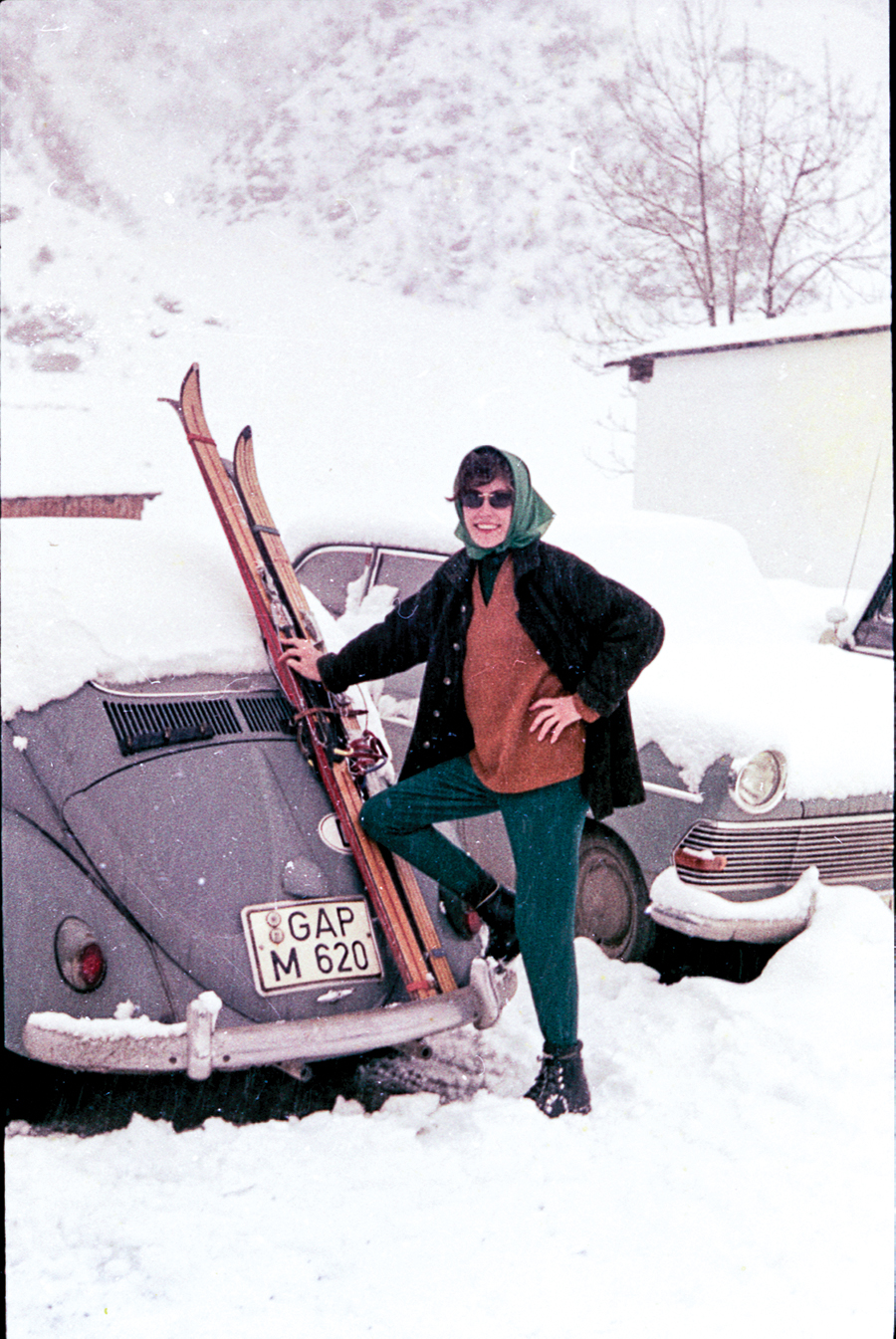

Adelheid “Heidi” Koob sailed to America aboard the Berlin, arriving on the 21st of May, 1961. She was coming to visit her own mother, who had left war-ravaged Germany at the end of the Second World War, intent on beginning a new life. “My mother and her three new daughters and her new husband picked me up in New York,” says Heidi, now 80 and married to Arthur Strelick, a retired member of the U.S. diplomatic corps. The “new” family drove south to their home in Fort Lee, Virginia. “After 14 or 15 years, seeing her again was not the same. Something broke away. Where was she when I was sick? Where was she when I went to school? She was not there.”

Heidi, who at 21 was already experienced managing hotels, didn’t want to stay in Virginia with her mother. She wanted to go back to New York. Then, one Saturday night on a date in Fort Lee, “I had a Coca-Cola and then I woke up the next day and I don’t know what happened.” She packed her suitcase and took a bus to New York. “Then I found out I was pregnant.”

The information Gessner obtained from the adoption agency shined as little light on his biological father as it had his mother. “He was in the military and he already had a family,” he says.

In New York, things went from murky to mysterious. Heidi, whose English skills were in the formative stage, got a job working at the Waldorf Astoria. As the time for her delivery approached, a friend at the Swedish embassy told her to go to Misericordia and advised her to pay cash. She delivered a 10-pound, 4-ounce baby at around 1:30 in the morning on Jan. 31. She had him baptized Karl Leo Koob in the hospital chapel on Feb. 2. She wouldn’t see him again for 55 years.

“They said I was sick and had to stay in the hospital,” Gessner says. The young mother left the baby.

“When I came back, they ask me for paper,” says Heidi. “I said, ‘What paper?’ Birth certificate. I don’t have any documents. ‘Did you register?’ I said, ‘No, I paid cash.’ That was it. There was no baby.”

For months, the new mother frantically tried to find her son. Finally, in June of ’63, she went back to Germany and the months of searching turned into years. She was looking for Karl Leo Koob, but Karl Leo Koob was about to become John Gessner.

She met Arthur Strelick, who attended Penn State University and worked for Pittsburgh Steel and NASA before joining the diplomatic corps, when he was a vice consul in Munich. In ’68 Heidi moved to Canada, using it as a base to hunt for her missing son. In 1969, Arthur proposed. As an alien attempting to wed a U.S. diplomat, Heidi was investigated by the FBI and the CIA. She told them everything, but there was no evidence of a child. Arthur was assigned to Sri Lanka, and they were married in ’69. Even he doubted his wife’s story.

Their postings included Vietnam — Gessner’s half-sister, also named Heidi, was born in September of ’74 — then Norway and Egypt. After Cairo, they were in India for two years, then Malta. Heidi, their daughter, was showing great promise as a dancer, eventually having a 14-year career with the ballet company in Ulm, Germany. She now teaches dance at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York.

At every posting, Heidi Strelick, the mother, paid particular attention to the children, to the orphanages. Buddhist. Catholic. It didn’t matter. She gave them food. She gave them clothes. “I think I carried a guilt with me,” she says, “to make me so strong to take care of lost children, adopted children.”

After Malta, the Strelicks were in Brazil. After Brazil it was Bonn, Germany. After Bonn it was Suriname. “We visit the Indians,” says Gessner’s mother. “I took hundreds of pictures of the Indians. I show it to them. They cried. They did like a cat. They turned it around, like a cat looks behind the mirror. I took pictures of their babies. They give me some gifts and I want to pay them. No, they want my flip-flops. The Hollander, they come to Suriname to paint. The color, light, people. It is heaven for artists.”

Next was Athens, Greece. Then back to America and, eventually, retirement. Gessner’s mother became a collector of antique jewelry. Arthur joined her in the pursuit, specializing in Russian watches. Then came 23andMe and its DNA match.

“I get a message around the end of September,” says Heidi. “Really strange. How tall is your father? How tall is your mother? How tall are you? How much do you weigh? What color are your eyes? On the 6th of October, it says you have three messages. I go in there. I fainted. It’s all red, from the top to the bottom. All red. I clicked further. ‘I’m your son. I’ve been looking for you all my life.’ I didn’t answer right away. You get hot and cold.”

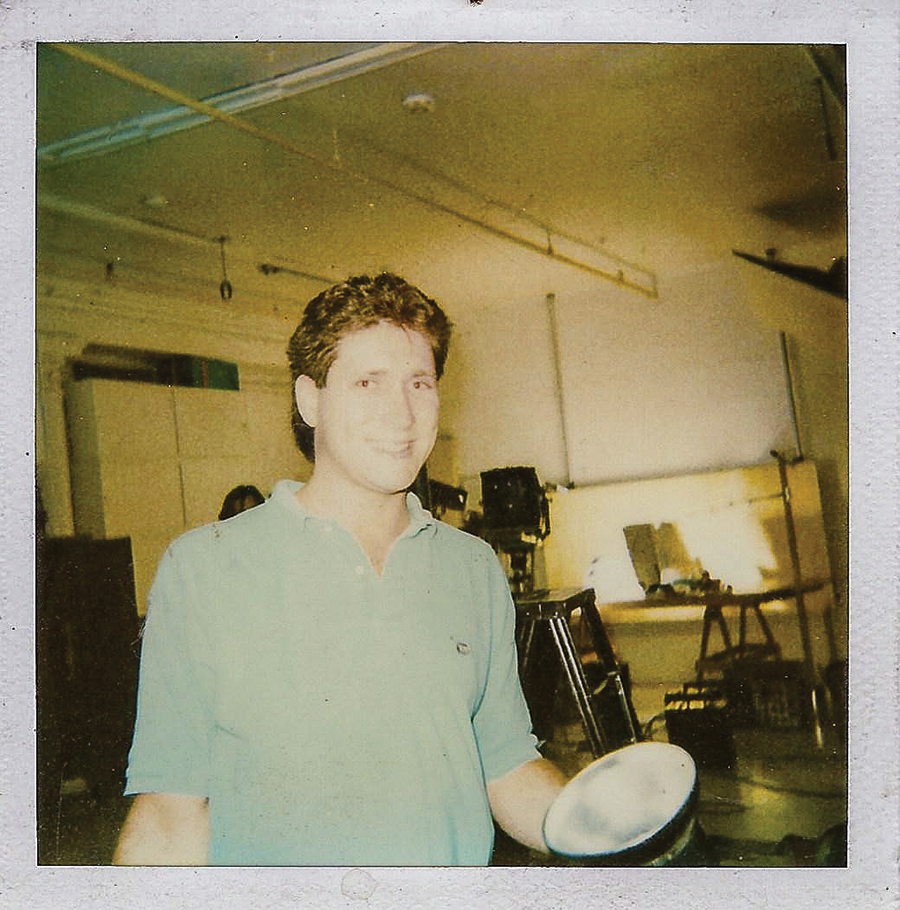

John Gessner, son, and Heidi Strelick, mother, investigated one another online. “It took me about a month. A lot of sleepless nights,” says Gessner. “I put my website in there. I just wanted her to know that it wasn’t a scam. I wanted her to know that I was a good person. That’s all I really ever expected.”

After Gessner returned that first call from a parking lot, they spoke on the phone every day, often for an hour or two at a time. John went to the Strelicks’ home in Delaware for Christmas and returned in January for his birthday — the second one they’d spent together.

“How does it feel? I cannot describe it,” says his mother. “I cannot write it. It’s in here.” She puts her hand on her chest. “All my life, taking care of babies, taking care of children and I prayed. And I’m still alive and I see the life I’ve given. I got my son. I don’t need much more anymore. I see him alive and healthy.”

Gessner fashioned a Christmas ornament, the gooey kind you bake in an oven, and every year he’d put it on his tree and make a wish that somehow he would find his mother. In far-flung corners of the globe, his mother did the same, hanging a tiny bell given to her by her father, making the same wish, that she would find the son she’d lost. After their first Christmas together, the silver bell fell off the tree and broke. It didn’t need repair. The mending had been done. PS

Jim Moriarty is the senior editor at PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.