Weymouth’s cultural mecca turns 100

By Bill Case

One hundred years ago, a remarkable couple made a remarkable house their home. Sitting commandingly atop Shaw’s Ridge east of downtown Southern Pines, the house of Katharine and James Boyd, built from a rough sketch into today’s 9,000-square foot rambling manor, shares its 21st century spirit with its 20th century soul, retaining its birthright as a haven for writers, musicians, in fact, artists of all kinds. It is the home of the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame as well as the North Carolina Poetry Society. It plays host to chamber recitals, jam sessions and contemplative strollers. And, since 1979, hundreds of writers-in-residence have padded down its hallways on cat feet, savoring the solitude of serious work in an enchanted place.

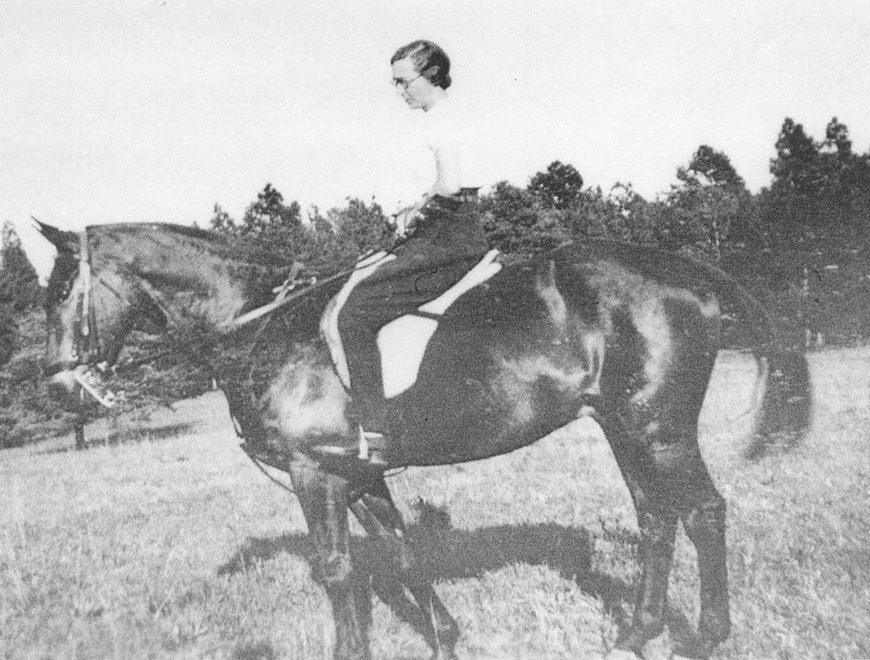

It is unknown precisely how the teenage Katharine Lamont made the acquaintance of the 20-something James Boyd. One biographer claims they met at a dance, possibly in New York, in 1916. A less likely scenario suggests that Katharine, an accomplished foxhunter with the Millbrook Hunt in New York, could have ridden to the hounds at Weymouth, where she would have encountered James, an avid practitioner of the sport. What is known is that in June 1916, Katharine became the owner of a 3.725-acre tract adjacent to the driveway entrance to Weymouth, quite an acquisition for a 19-year-old. She built a small house on the property, the “Lamont Cottage,” now called the Gatehouse.

Their relationship blossomed during the summer of 1917, and the two began entertaining thoughts of marriage. Both the Boyd and Lamont families were of similar wealth and social strata. Katharine’s father, Daniel Lamont, was vice president of the Northern Pacific Railroad and served as secretary of war during President Grover Cleveland’s second term. James’ ancestors — primarily through the efforts of his grandfather, James Boyd, and his father, John Yeomans Boyd — amassed the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania-based family’s fortune through investments in coal, steel, railroads and banking.

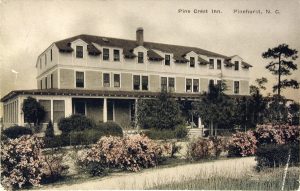

The extended Boyd family had begun vacationing in Southern Pines shortly after 1904 when grandfather James, in search of a Southern retreat, purchased vast parcels from three of the Sandhills’ pioneering families — the Blues, the Shaws and the Buchans. Eventually, the elder James would own over 1,500 mostly pine-forested acres. He called his estate “Weymouth Woods,” so named because its tall longleaf trees reminded him of majestic pines he observed in the seacoast town of Weymouth, England. To serve as the family’s residence, the elder James acquired an existing home adjacent to his acreage.

Grandson James attended the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and later Princeton University (also the alma mater of his father, John Yeomans Boyd, and his brother, Jackson) where he became the managing editor of the college’s literary magazine. After his graduation in 1910, he worked briefly at the Harrisburg Post writing stories and drawing cartoons before enrolling at Trinity College in Cambridge, England, where he received a master’s degree in English literature. He returned to Pennsylvania, taking a short-lived teaching position but ill health forced him to resign in 1913. He recuperated at Weymouth and became increasingly involved in foxhunting, forming the Moore County Hounds with Jackson a year later.

With a boost from Southern Pines friend Frank Page (who put in a good word with his publisher brother Walter Hines Page), the young James Boyd secured a job in September 1916 in New York with the Doubleday, Page publication Country Life in America. Boyd remained in the position just a few months, a recurring theme shared with his previous brushes with employment, opting instead to volunteer with the American Red Cross in New York, where he aided in the procurement of ambulances to support the war effort in Europe.

This served as a prelude to Boyd’s enlistment in the U.S. Army Ambulance Service in August 1917, soon after the U.S. entered World War I. Irksome sinus problems had previously caused his rejection for service by the Army and the National Guards of Pennsylvania and New York. He finally passed the physical after a corrective procedure.

Despite the certain knowledge that the war would soon separate them, James and Katharine were married at the Lamont family residence in Millbrook on Dec. 15, 1917, and enjoyed an extended honeymoon at Weymouth. In February 1918, Boyd received orders to report to his unit. In July, 2nd Lt. Boyd arrived in Italy, where he took charge of the Army ambulance service there. In August, he was transferred to France, where his unit supported the Saint-Mihiel campaign and the Argonne offensive, both critical events in turning the tide in the Allies’ favor. The exhausting duties proved punishing to Boyd’s frustratingly fragile health and resulted in several hospitalizations. He was discharged from service on July 2, 1919 (his 31st birthday), and returned home to Katharine.

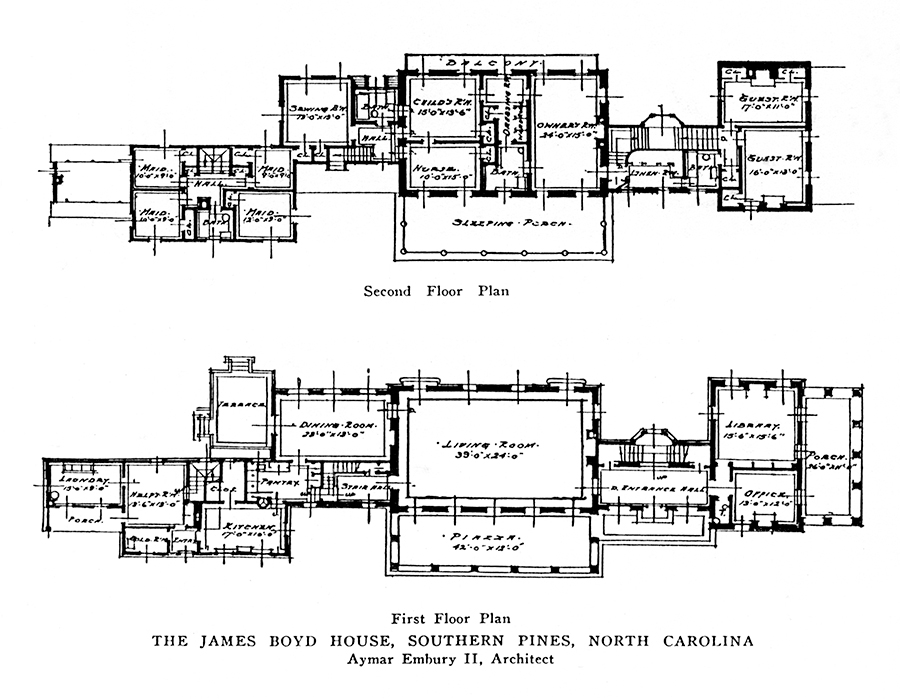

James’ father had passed away before the war, in March 1914, at age 51. When the heirs divvied up the estate’s far-flung assets, James wound up with most of Weymouth. After returning from Europe, James and Katharine began making plans to build their new home up the ridge from the former site of James’ grandfather’s house (the elder James had passed away in 1910), which the family had dismantled and moved in 1920. The architect they chose was Aymar Embury II — yet another Princeton alum — then in the process of building the Mid Pines Inn and Country Club. Using James Boyd’s drawing as a starting point, Embury designed a house that pleasingly blended elements of Colonial Revival and Georgian architecture. The exterior was said to resemble the Westover, Virginia, home of Colonial planter William Byrd. Landscape designer Alfred Yeomans (surprise, another Princetonian) laid out new Weymouth gardens and a swimming pool, bordered by a serpentine brick wall. A stable and kennels were constructed as well.

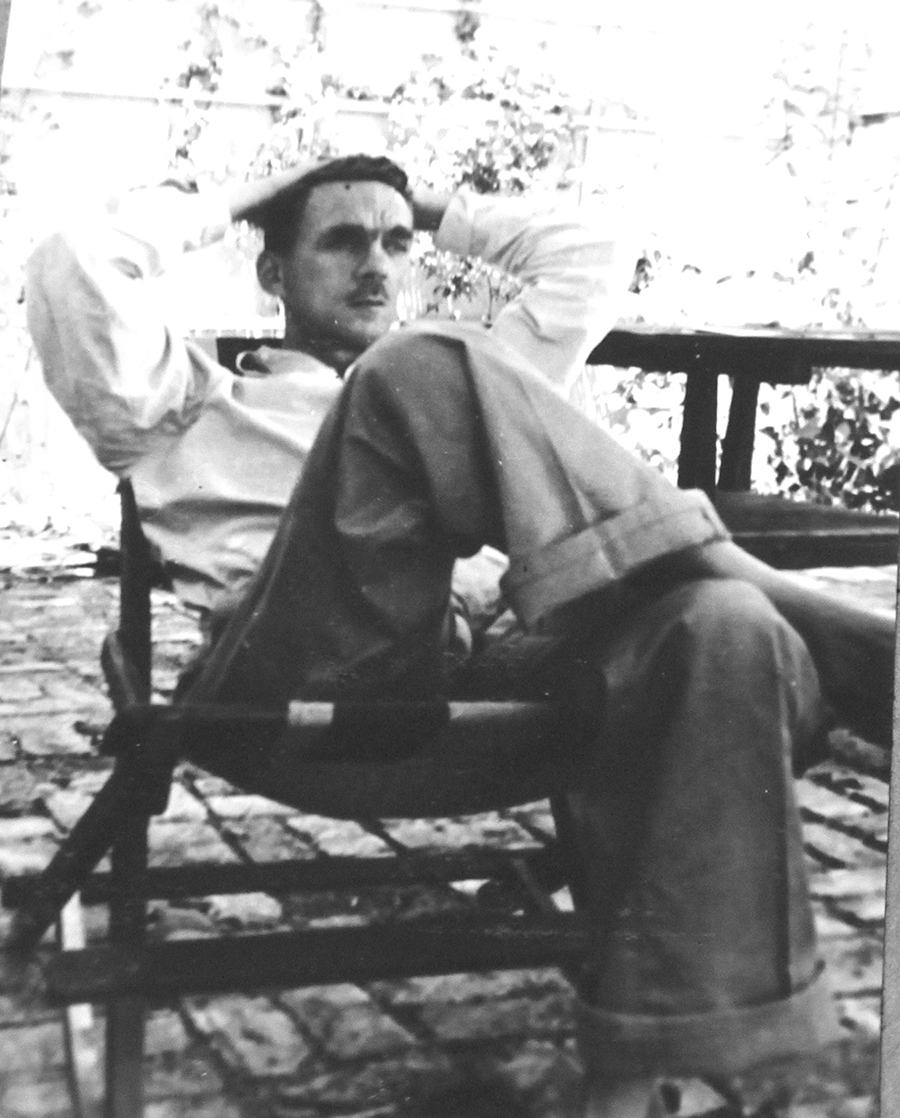

James Boyd became firmly ensconced as Southern Pines’ foremost country squire. He checked all the requisite boxes: Master of the Hounds; owner of a splendid home on vast acreage; scion of an old-line family (as was his wife); and wealthy but not flauntingly so. He would never have to work to make ends meet. And, frankly, up to 1921, his work résumé was wafer thin. Aside from his military hitch, Boyd’s longest tenure of employment at the three jobs he’d held in his 33 years was about nine months.

With a background in literature and having successfully published a few short stories as a schoolboy, Boyd thought perhaps he could make something of himself as a writer. He figured that Weymouth, relatively free of distractions and enjoying three seasons of comfortable climate, would provide an ideal environment for the solitary business of writing.

So, he began.

Boyd’s first objective was to craft a short story for one of the numerous New York magazines, at the time a prime outlet for writers. He settled in to work at Lamont Cottage, where he and Katharine resided prior to the completion of their new home. In mid-1920, Scribner’s magazine editor, Robert Bridges, paid $100 for the piece “The Sound of a Voice,” though the first Boyd creation to hit the newsstands was his short story “Old Pines,” published by Century Magazine in March 1921.

Finding his stride in his new home, Boyd accelerated his production of short stories, dictating them to Katharine in his downstairs study (now called the foyer) next to the house’s library. The study featured a door to a side porch. According to Dotty Starling, the archivist for the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities, it “was frequently a thoroughfare for the family heading outside.” And the Boyd family was growing. James Boyd Jr. was born in 1921, followed by the births of Daniel Lamont Boyd in 1923 and Nancy Boyd in 1927.

Writing short stories was fine, but to be considered a serious author, Boyd felt he needed to write books. In 1922, he began composing a work of historical fiction set largely in Edenton, North Carolina, during the Revolutionary War. The plot involves the dual dilemmas faced by young Johnny Fraser, the son of a British Loyalist father, and a mother favoring independence from the crown.

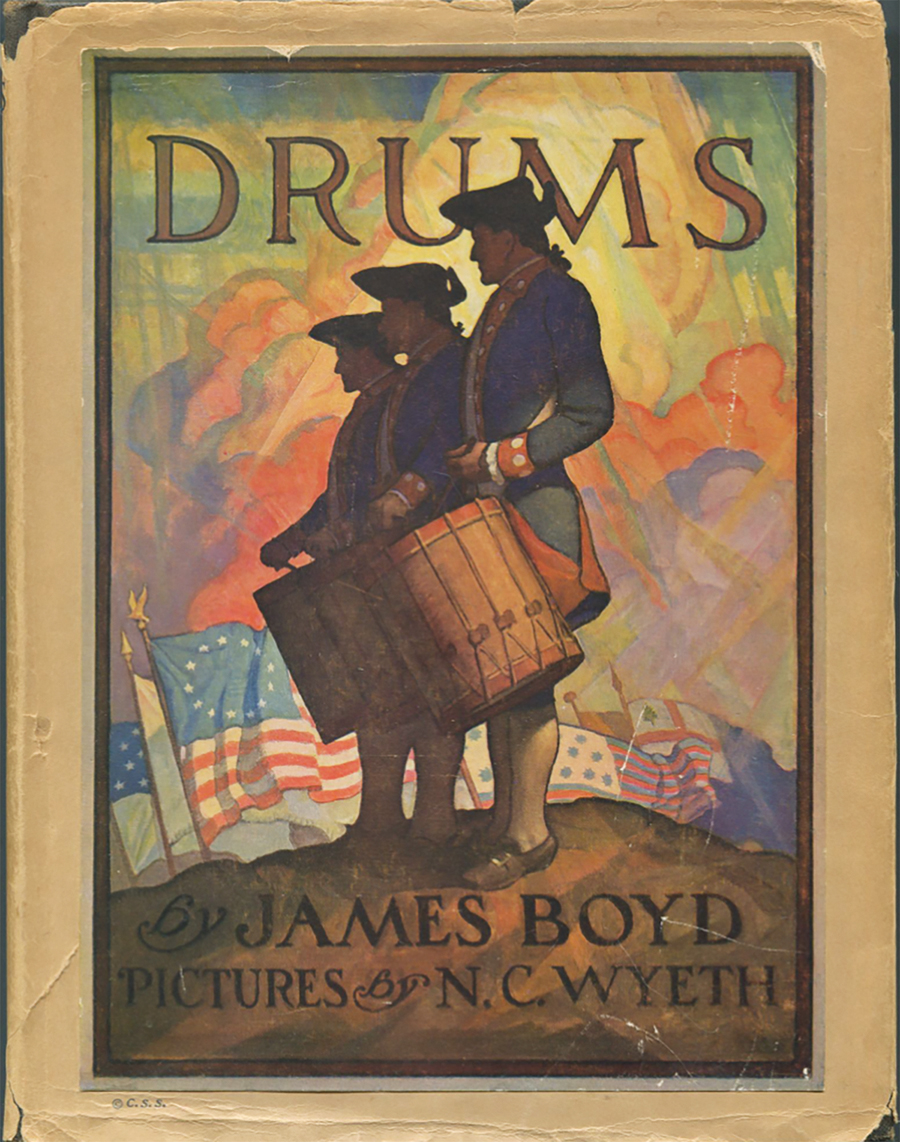

Boyd submitted Drums to Charles Scribner’s Sons, and his manuscript came to the attention of Maxwell Perkins, one of publishing’s most storied editors. Perkins would not only edit the works of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe; he discovered those superstars. Perkins liked what he saw in Boyd’s work and guided the fledgling novelist through the editing process. Published in 1925, Drums was reprinted in 1928 as part of the Scribner’s “Illustrated Classics Series,” with illustrations by N.C. Wyeth.

Drums was a major hit. Critic E. C. Beckworth of The New York Evening Post hailed it as “the finest novel of the American Revolution that has yet been written.” The book’s success resulted in four printings in the first month after release, and 40,000 sales in five months. The breakthrough numbers were welcome news to Boyd, while advancing Perkins’ reputation for discovering unknowns able to craft captivating and profitable novels.

Brimming with confidence, Boyd was soon at work on a second historical novel, Marching On, set in Wilmington, North Carolina, during the Civil War. It features a seemingly dead-end love affair between a poor farmer and the daughter of an aristocratic planter. Perkins did not care for Boyd’s proposed one-word title, “Marching.” In a November 1926 message Perkins writes, “I think ‘Marching On’ solves the problem. ‘Marching’ alone, as a present participle, has a monotonous suggestion, and an indefinite one. But ‘Marching On’ suggests a goal.” The 1927 book outsold Drums.

Boyd and Perkins would become lifelong friends. Unlike Hemingway, Fitzgerald or Wolfe, Boyd never craved the limelight. In his biography, James Boyd, David Whisnant writes that while Boyd was serious about his craft, “in his characteristically diffident way he rarely took himself very seriously in public . . . He neglected to create and protect the kind of public image most writers instinctively make . . . He minimized the seriously artistic side of his personality and accentuated the ‘country squire’ side.”

Boyd’s third novel, Long Hunt, in 1930, is a frontier adventure tale set in North Carolina’s western mountains. Among the book’s admirers was Look Homeward, Angel author and fellow Scribner’s contributor Thomas Wolfe, who informed Boyd that “ . . . Long Hunt is a beautiful book, and aside from personal feelings I am proud to know the author. There is not a poor line or a shoddy page in it . . . It has in it the vision of mighty rivers and of the enormous wilderness and of the richness and glory of this country.”

Boyd’s rise and Scribner’s connections led him to friendships with numerous acclaimed writers. Literary giants began making pilgrimages to Weymouth to hobnob with the hospitable Boyds, including Wolfe, Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson (Winesburg, Ohio), Struthers Burt, John Galsworthy, Laurence Stallings, Perkins and Paul Green (The Lost Colony), who became his best friend. All things literary were discussed in amiable fashion during these visits, one notable exception being Fitzgerald’s inebriated and insulting critique of his host’s fourth novel, Roll River, during a three-day stay in 1935. Wolfe felt enough at home at Weymouth that he unhesitatingly hauled his massive 6-foot, 6-inch frame through an unlocked window into the great room, where he slept sprawled on the floor.

The constant flow of visitors caused the Boyds to add two new wings to the house. James relocated his writing area to a spacious room on the second floor, now the N.C. Literary Hall of Fame. An admiring Wolfe credited Boyd and his guests with giving “North Carolina a literature before it had native writers of its own.”

The Boyds’ friends, whether they were authors, foxhunters or farmers, usually stayed for dinner, engaged in charades and, given sufficient lubrication, sang whimsical songs with madcap lyrics in which they poked fun at one another. Daughter Nancy Boyd Sokoloff later remembered that the family’s doors “were always open — to friends and neighbors who came to talk about politics, farming and gardening, writing, horses and dogs, history, music, education. That’s the way my parents hoped it would always be.”

Boyd wrote one more book of historical fiction, Bitter Creek, set in the cattle country of Wyoming circa 1890. It was the least successful of his historical novels. In the fall of 1940, he found a new calling. Aghast that democracy had virtually disappeared in Europe and that Nazi Germany was making some headway in America with its insidiously false propaganda, he, along with good friend and U.S. Solicitor General Francis Biddle, decided to do something about it. They believed that the Nazis’ lies could be effectively combated by a series of radio plays celebrating the Bill of Rights and the virtues of democracy. Boyd assembled a team of the country’s finest writers, each of whom agreed to write one radio play gratis. They included Orson Welles, William Saroyan, Archibald MacLeish and Paul Green. The shows needed actors, and Burgess Meredith (later the grizzled trainer in Rocky) rounded up cast members willing to donate their services. Boyd arranged for half-hour Sunday afternoon broadcasts of the plays on CBS Radio, again gratis.

Because no one was being paid and the playwrights were uncensored, Boyd named his enterprise “The Free Company.” Overcoming the difficulties of coaxing writers with towering egos to work free on a tight schedule, he orchestrated the broadcast of 11 plays between February and May 1941. Upward of 5 million listeners tuned in.

Soon after the final airing, Boyd acquired ownership of The Pilot newspaper and infused funds to stabilize the paper’s operations. As editor-publisher, he contributed a wide variety of writings, ranging from editorials upbraiding powerful North Carolinians for failure to provide meaningful employment opportunities for Blacks to whimsical verse. Poetry became a frequent mode of expression. Boyd’s final book, 18 Poems, was published in January 1944.

During a February 1944 engagement at his alma mater Princeton, Boyd suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died at age 55. His demise posed a daunting challenge for Katharine, who assumed control of The Pilot. She became an excellent journalistic writer in her own right. Her “Grains of Sand” column won awards. Though she was shy, Katharine’s editorials proved to be even more outspoken than her late husband’s on matters of civil rights. She even scolded legendary Sen. Sam Ervin, whom she felt had not done enough to secure the ballot for Blacks. Katharine would run the paper for a quarter-century, selling it to Sam Ragan in October 1968.

Her achievements as a pioneering female publisher were dwarfed by her philanthropy to an array of artistic organizations and local institutions. In 1963 she donated 400 acres of Weymouth land to the state, thereby establishing the Weymouth Woods – Sandhills Nature Preserve. Another 30-acre parcel was given to the Episcopal Diocese for the establishment of the Penick Village retirement community.

As Katharine aged, she worried about what would happen to the Boyd House and surrounding 200 acres after she was gone. By the mid-1960s, she was the last family member left in the Sandhills. Children James Jr. and Nancy resided out-of-state. Third child Daniel, a hero in World War II, perished in a 1958 accident. Katharine’s brother-in-law, Jackson, had moved back to Harrisburg.

In 1967, Katharine, now 70, explored whether one of her favored charities, Sandhills Community College, could make good use of Weymouth while also preserving it. SCC was then brand new; its first classes were held in 1966 in various temporary locations. Raymond Stone, then the president of the fledgling college, expressed interest in the concept, perhaps as a writers’ workshop, a continuing education center or a venue for seminars.

It was music to Katharine Boyd’s ears. It seemed SCC was the best, and probably only, hope for the long-term survival of her beloved estate. In an informal arrangement with Stone, she welcomed SCC horticultural students to use the grounds. Thereafter, Katharine established a trust, effective upon her death, naming SCC as beneficiary of Weymouth’s remaining real property. Katharine fervently hoped the college would keep Weymouth as is, but sensitive that financial considerations could make a “hands-off” policy impractical, she did not seek to permanently hamstring the college. Correspondence from the time indicates Katharine did not oppose SCC’s selling lots for housing along Connecticut Avenue after her death.

By the early ’70s, when Katharine was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, James Jr. took over discussions with Stone and SCC. He wrote in a 1972 letter to Stone that the trust would not constrain SCC when Katharine passed away, provided SCC was agreeable to preserving the Boyd House and 70 acres of virgin longleaf timber forest. Katharine’s son indicated that upon his mother’s death, he and sister Nancy intended to “terminate the Trust and turn the whole Weymouth Campus over to the control and jurisdiction of the College to do as they wish.” Concerned that financial considerations might mandate a different course, the college balked at promising the permanent survival of either Boyd House or Weymouth’s pine forest.

Following Katharine Boyd’s death in February 1974, Dr. Stone, on behalf of the Sandhills College Foundation, accepted tender of Weymouth’s property by the trust’s two remaining trustees, banker Norris Hodgkins and Dr. R.M. McMillan (James Jr. and Nancy declined to serve). In addition, Katharine’s will bequeathed the school $75,000 for Weymouth’s maintenance. SCC would give “the old college try” to making use of Weymouth for its horticultural activities. The college also scheduled continuing education and inhalation therapy sessions at Boyd House. But Stone quickly concluded it was impractical to hold regular classes six miles from the main campus on Airport Road. Thus, the house essentially sat vacant.

Worse yet, the formerly elegant home became an intractable money pit for SCC. In an October 1976 article in the Pinehurst Outlook, Stone advised that taxes and heating costs for the house were running over $7,000 annually. Repainting the exterior had cost $15,000. He estimated it would cost a mind-numbing $250,000 to restore the now ramshackle house to its former glory.

Several of Stone’s quotes raised eyebrows. “It [the house] has no architectural value,” he wrote. “Let’s face it, the house is a liability.” The SCC president still wanted his school to build a cultural arts center, but not at Weymouth. “I would like to see the property sold,” confided Stone, “and the proceeds used to build a fine memorial on this campus [Airport Road] to Katharine Boyd.” Dr. Stone finished with this nugget: “We have complete freedom on what to do with the property.”

Sam Ragan wrote in The Pilot that “it would be a shame to see the old Boyd estate sold for another land development . . . Weymouth is a priceless part of our heritage. It would be unthinkable not to keep it.” Ragan thought Weymouth would make for an ideal cultural arts center.

But talk was cheap. Was any existing Moore County nonprofit organization in a position to outbid developers for the property (estimated market value $1 million), save the Boyd House and dedicate Weymouth to a public use such as Ragan’s suggested cultural arts center? There was not.

James Boyd’s best friend, fellow author Paul Green, started the ball rolling toward creating one. After learning that officials of the Sandhills College Foundation were meeting to address SCC’s Weymouth difficulties, the 82-year-old Green drove down from Chapel Hill to attend. He pleaded with the college’s higher-ups to allow time for a Friends of Weymouth entity to form and raise funds to buy the property. He then pledged $1,000 himself. “Weymouth is waiting,” he said with rhetorical flourish. “Does it wait for life or death?”

Howard Muse, president of the Sandhills Sierra Club, said, “It’s the timberland that concerns us. It contains what we believe to be the last sizeable stand of virgin growth of longleaf pines.” Both Muse and Joe Carter, a naturalist-ranger with the Weymouth Woods – Sandhills Nature Preserve, focused attention on the presence of an endangered species in the woods — the red-cockaded woodpecker.

Elizabeth Stevenson “Buffie” Ives, the sister of former presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, and four-star Navy Admiral I. J. “Pete” Galantin joined forces in late 1976 to form the Friends of Weymouth as a fundraising entity with the admiral serving as president. R.W. Drummond of Whispering Pines donated $20,000 to kick off the project. It was a beginning.

The Friends then explored whether the North Carolina state government might aid the cause by purchasing the woodland portion of Weymouth (about 200 acres) and incorporating it into the adjacent Weymouth Woods – Sandhills Nature Preserve. Gov. Jim Hunt and Howard Lee of the Department of Natural Resources responded affirmatively and sought assistance through the North Carolina’s Nature Conservancy. The Conservancy conditioned any commitment of funds on the Friends’ ability to raise the money to acquire the Boyd House and its surrounding 26 acres. While SCC was unwilling to wait indefinitely to market the property, it did grant a one-year option to the Friends and the Nature Conservancy to buy the entirety of Weymouth and, later, the college agreed to extend the time for exercising the option to April 5, 1979.

As the deadline loomed, the campaign picked up speed. Buffie Ives persuaded former first lady Lady Bird Johnson to make a speech at a Weymouth fundraiser at Pinehurst Country Club in January 1979. In her speech, she described Weymouth “as a place that breathes life into creativity.” She added, “I wish I could have been privy to the fireplace conversation when Thomas Wolfe, or Sherwood Anderson, or John Galsworthy, or Adlai Stevenson, that master wordsmith, were here.”

The event did much to close the fundraising gap. Finally, on March 23, 1979, the Friends of Weymouth and the Nature Conservancy informed SCC that they were prepared to exercise their option to purchase Weymouth. The cost was $700,000 and the property changed hands.

The opening ceremony was held at Weymouth on the east lawn on a hot and sunny 20th of July. Gov. Hunt summed up the day’s significance this way: “James Boyd made this a place for inspiration . . . What has happened here has inspired all of us.”

The Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities was born, and the Boyd House was reborn. Of course, the raising of money for the center was not over with the acquisition; it continues today and will never end.

The outcome would have especially gratified Katharine Boyd. Her beloved woods are intact; Sandhills Community College, one of her favorite charities, is thriving; and Weymouth has become a cultural arts center as she had hoped. A hundred years later, it’s just how she dreamed it. PS

Dotty Starling’s tireless research and generosity with her time contributed to this story. Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.