The story of an exceptional kid

By Stephen E. Smith

Photographs from the Weymouth Center Archives

Dan, Katharine and Jim Boyd Jr.

“The best of that whole Boyd bunch was Dan, the one who was killed in a motorcycle accident in San Francisco,” Glen Rounds said while lounging in his front yard on a sunny spring afternoon 30 years ago. He was parsing the James Boyd family, the “first family” of Southern Pines, the clan responsible for many of the aesthetic and cultural pleasures our quaint hometown offers.

“The older son, Jim, was something of an oddball,” Rounds continued, “but Dan . . . Dan was an exceptional kid.”

When Rounds spoke, I listened. Intently. In addition to authoring 100 children’s books and receiving a slew of state and national awards for his writing and illustrating, Rounds had his arthritic fingers on the pulse of Southern Pines. He knew what there was to know about everyone in town worth knowing about, and he served up his edgy opinions freely and with an occasional sprig of rancor and a dash of humor. Any praise, however slight, he might lavish on Daniel Boyd, the second son of historical novelist James Boyd and his wife, Katharine, was a high recommendation indeed and worthy of investigation.

“Dan was awarded the Silver Star during the Battle of the Bulge,” Rounds went on, “and when he got back in town, he never once mentioned it.”

I knew nothing of Dan Boyd, so during my next visit to the Southern Pines Library, I plundered through fusty back issues of The Pilot bound in bulky, outsized volumes, and discovered the January 1, 1959, front page headline: “Daniel Boyd Killed in California Last Tuesday in Traffic Accident.”

The timeworn newsprint was crumbling and much of the story was missing, but the essential facts were there: “Daniel Lamont Boyd, 34, the son of Mrs. James Boyd of Southern Pines, was fatally injured Tuesday of last week (Dec. 23, 1958) in San Francisco, where he had made his home.” Boyd was homeward bound from the city center when a car crossed the yellow center line and struck his “motor bike” (a lightweight scooter of some variety, possibly a Vespa) head-on. Dan was transported to the hospital, where he died without regaining consciousness.

The article also noted that Katharine Boyd, publisher of The Pilot, flew to San Francisco as soon as she received word of her son’s death, and that “News of the tragic accident was received with great sorrow in the community.” Although Dan hadn’t lived in Southern Pines in several years, he had “maintained earlier friendships with many people.”

If Rounds wasn’t exactly correct about the motorcycle, he was spot on when it came to Boyd’s military record. Dan served with the 60th Engineering, 35th Infantry Unit, which fought from Normandy, through the battles for Saint-Lô and the Bulge — 78 years ago this month — to the end of the European campaign. It was during the Battle of the Bulge that Dan distinguished himself and was awarded a Purple Heart and the Silver Star for gallantry under fire.

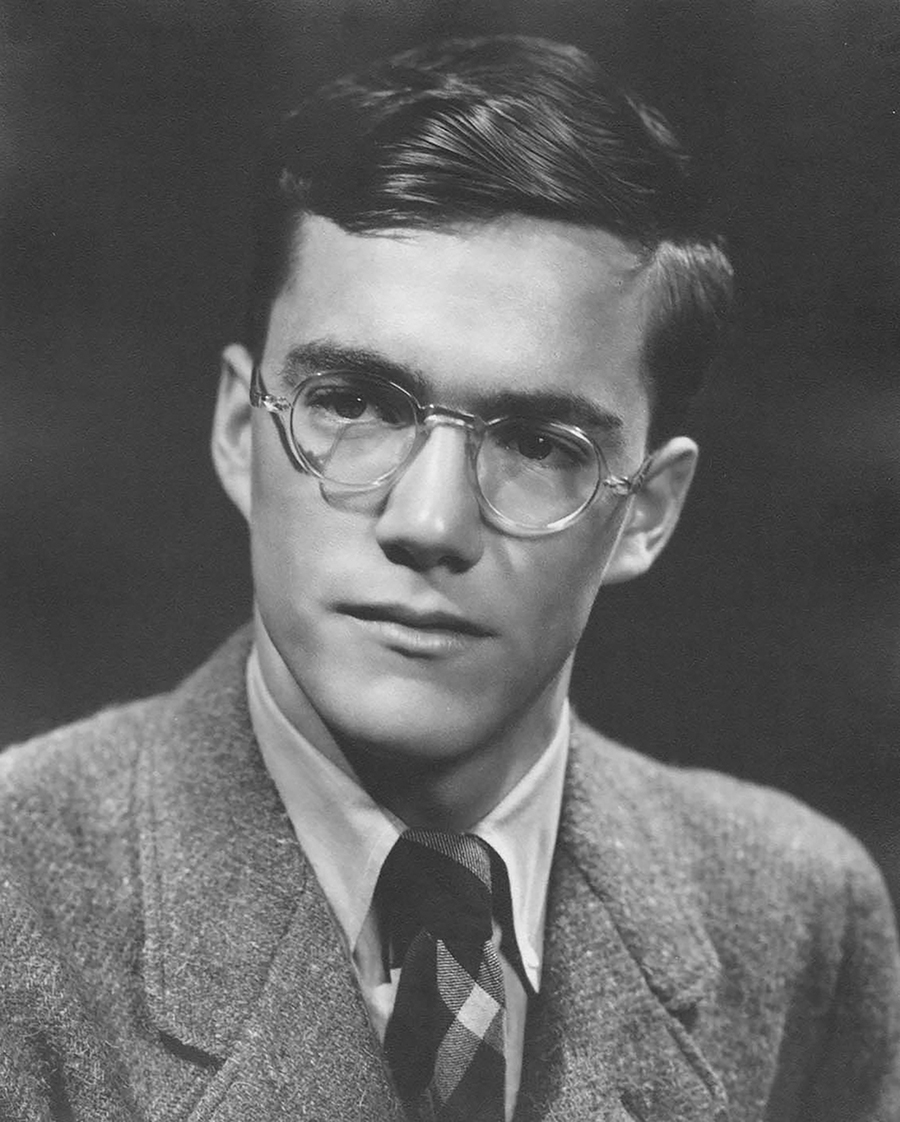

Dan Boyd before going overseas

The Army doesn’t retain records detailing the courageous actions of individuals who have been awarded the Silver Star, but the Friday, Feb. 9, 1945 issue of The Pilot reprinted an official press release:

“Corporal Daniel L. Boyd, 34677486, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, for gallantry in action near ————- France on 13th December 1944.

“During the crossing of the ————– River near ————–, Corporal Boyd was in charge of an assault boat operating in a sector which was subjected to intense machine gun fire from enemy emplacements located only 150 yards from the river. When he saw a nearby boat capsize in mid-stream after receiving a burst of machine fire, he immediately paddled his boat to the scene and rescued five heavily clothed soldiers from drowning in the swift current. After he had brought the men to the friendly shore, he started to assist them to an aid station when one of the men collapsed as a result of a wound he had suffered. Corporal Boyd placed him in a sheltered position, administered first aid, and then continued to the aid station with the other men. Finding a shortage of medical personnel, he personally returned to the wounded man he had left behind, in the face of withering enemy fire, and with the aid of a litter bearer, succeeded in evacuating his comrade. Corporal Boyd’s intrepid deeds and resourceful performance in the face of heavy odds were responsible for saving the lives of five of his comrades and are in accord with the finest tradition of the United State Army.”

The January 1959 Pilot notes that “With fighting going on across the river where American units were isolated, Boyd went out, found one of the engineers’ boats and, under heavy fire, ferried across sufficient men to win the action.”

Valor in military service was nothing new to the Boyd family. Novelist James Boyd Sr. served as an ambulance driver in France during World War I, and Dan’s cousin, Seaman 1st Class John Boyd, who had grown up in what is now the Campbell House, died in the Battle for Guadalcanal when the USS Barton, the destroyer on which he was serving, was sunk in a night action in November 1942.

My curiosity concerning Dan Boyd’s life and death might have ended there, but Rounds’ recommendation resonated with me whenever I attended a cultural and social event held at the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities. A few years later, I was researching James Boyd’s relationship with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherwood Anderson in the Firestone Library at Princeton and the Southern Historical Collection at UNC when I happened upon letters from Dan to his parents, chatty missives about life at boarding school, football games and, oddly enough, railroads. His letters were peppered with allusions to the trains and drawings of locomotives.

The mystery of Dan Boyd’s life unraveled further when Dotty Starling, Weymouth’s dedicated archivist, lent me a copy of An Oral History of Weymouth. Published in 2004, the history gathered the reminiscences of friends of the Boyd family and the recollections of longtime employees. Many of the details of Dan Boyd’s short life are revealed in those collected memories.

I learned that in the ’20s and ’30s, the James and Jackson Boyd children had grown up together, playing in the pasture behind Weymouth, riding horses, and sharing in the privileges afforded by their parents’ wealth. They all attended kindergarten and elementary school at the private Ark school, initially located on the corner of Ridge Street and Connecticut Avenue on the Weymouth property. (The foundation of the school is still clearly visible, a giant magnolia rising from what must have been the building’s basement.)

Longtime Pilot reporter and editor Mary Evelyn de Nissoff remembered her days attending the Ark in a 2001 interview: “Two English ladies ran it. In the morning they welcomed the children with a handshake and had a cup of tea with them before classes began. In the afternoons the children went down into the basement where there were iron cots . . . where the teachers read aloud to them.” All three of James and Katharine’s children, Jim Jr., Dan and Nancy, the youngest, attended classes with Mary Evelyn. “They (the Boyd children) rode, of course. They were into horses and they smelled of horses. Nancy didn’t, but Dan did.”

A life of privilege notwithstanding, the Boyd household was not always a peaceable kingdom. Jim Jr. and Dan, brothers of very different temperaments, often argued, and their mother had difficulty maintaining domestic harmony. In a scrapbook preserved in the Weymouth Archives, an unidentified family poet recorded the domestic discord in rhymed iambic pentameter:

Thus while Dan offers up his soul

To knowledge and each day grows thinner,

James lies in bed and eats his dinner;

And while Dan toils o’er Latin grammar

James turns out mediocre verses

Of fulsome amatory tone

And sends them round to all the nurses.”

Dan Boyd

If Jim Jr. lacked motivation, Dan was obsessed — with trains. He decorated his room with railroad posters, collected electric trains, and snapped hundreds of photos of art deco diesel and steam locomotives — massive pufferbellies with all the machinery bolted to their boilers — which are now preserved and cataloged in the Weymouth Archives with other Boyd family papers.

The anonymous family poet also offers a prediction:

That some day, trudging down the track

In broken hat and hobo’s breeches,

He’ll [Jim Jr.] hear a train behind his back

Come rattling over frogs and switches

And, looking up as it goes past,

See seated in his private car

The road’s vice-president, D. Boyd,

Smoking a fifty-cent cigar!”

Dan and Jim Jr. were eventually shuffled off to Millbrook School, an academy for students in grades 9-12 located in Millbrook, New York. During those years, they wrote letters to their parents that conveyed a strong sense of family and a guarded affection for one another. Dan wrote about trains and drew locomotives on Millbrook stationery letterhead.

After completing their studies at Millbrook, Dan matriculated at Princeton, his father’s alma mater, while Jim Jr. attended UNC. When the war interrupted their studies, Jim joined the Coast Guard and Dan enlisted in the Army and fought in decisive battles in Europe. After the war, the brothers completed their degrees and Dan married Rhoda Whitridge in 1948 and went west to work with the Southern Pacific Railroad in Eugene, Oregon, eventually settling in San Francisco.

In 2002, Weymouth board member Bea O’Rand interviewed longtime Southern Pines luminary Voit Gilmore, who knew the Dan Boyd family well in the 1950s: “We knew of his connection with his very generous work with the arts council and arts groups in San Francisco. We knew the exact street where he was on his motorbike and got hit. Every time I go by that intersection now, it just breaks my heart that that happened. It was a steep hill on Polk where you come up and go over. The problem always is that if the traffic light goes against you and you’re going up the hill you have a terrible time, you need to get over to the middle of the intersection which is what he did and got hit because of a car.”

Dan Boyd with gardener Hilton Walker at Weymouth

Flossie Carpenter, a longtime employee of Katharine Boyd’s, recalled the effect Dan’s death had on his mother: “Now that’s when Mrs. Boyd went off, the morning that she got the message that he had been killed. Her mind was no more good. She tried to do but she couldn’t. . . . She stayed that way for about three years.”

Mary Evelyn de Nissoff, who suffered tragedy in her own life, keenly comprehended Katharine’s suffering. “ . . . I can understand what she was going through. She never got over it, because it leaves this great hole in your stomach that is never filled up.”

As a family, the Boyds participated in bettering the community in which they lived. Katharine contributed anonymously to the education of many local children. The family gave us the Weymouth Woods Sandhills Nature Preserve with its 7 miles of hiking trails and visitor center and exhibits, contributed to the Southern Pines Library, maintained what is now the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities, and provided funds for the Boyd Library at Sandhills Community College. They worked to beautify the town and protect the pines that line our streets and shade our homes. The oldest living longleaf pine — its seed germinated in 1548, a survivor now of what was once the largest ecosystem in North America — thrives still on the Weymouth property.

In 2002, Rhoda Boyd, Dan’s widow, was driving with her granddaughter outside San Francisco when a redwood fell on her car, killing her instantly. Her granddaughter survived without injury. Dan and Rhoda Boyd are interred in Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in San Mateo County, California, far from Dan’s childhood home.

On that spring afternoon 30 years ago, Rounds, who knew something about humor and its understated uses, continued lauding Dan Boyd, offering up examples of his keen wit and artistic nature. As the afternoon wore on, the Southern Pines Middle School dismissed, and crowds of children began wandering up Ridge Street.

“Let’s go inside and have a drink to Dan Boyd,” Rounds suggested. “I don’t like to sit out here when these kids go by. They make too much noise.” Then he smiled. “But I’ll tell you what: When they’re gone, I go out and pick up their pencils.” PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.