Cultivating Community

Caroline Stephenson steps out from behind the camera

By Wiley Cash • Photographs by Mallory Cash

According to filmmaker Caroline Stephenson, “It’s all about storytelling.” She should know. She was born and raised in rural Murfreesboro, North Carolina, where she grew up surrounded by stories and storytellers. Despite the rich culture around her, as a young person, Stephenson believed that real art could only be found outside Hertford County. Her father, a retired professor and writer, and her late mother, an architectural historian, regularly traveled with the family to places like Norfolk, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and metropolitan New York, where they would visit museums and view films in art house theatres.

“That made a big impression,” says Stephenson, especially the films. “I wanted to do that.”

The restlessness that Stephenson felt as a coming-of-age artist in rural eastern North Carolina manifested itself not only in her desire to create, but also in an all-too-familiar angst-driven urge to leave home. Like so many young people who think opportunity and adventure are waiting somewhere else, Stephenson says that she “couldn’t wait to get out of there.”

First, she spent two years at St. Mary’s School in Raleigh, and then two years at Boston University before transferring to Columbia College Chicago, where she received her Bachelor of Arts in film. Soon, she was living in Los Angeles, beginning a career that would carry her to places like Prague, Vienna, Athens and Budapest, working as an assistant director on sets for films and television shows like Empire, House and, currently, Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan.

After marrying fellow filmmaker Jochen Kunstler and having two children, Stephenson felt a call to home. She and her young family moved back to Murfreesboro in 2010, where Stephenson came to terms with Hertford County’s rich cultural heritage as well as its incredible challenges. The county is 60 percent Black, and historical inequities in everything from education to home ownership serve to compound a poverty rate of 22 percent, much higher than the state average. The county’s struggles have also resulted in a dogged spirit of determination that immediately inspired Stephenson and her family to dedicate themselves to supporting the community.

“I’m driven by the incredible people where I’m from,” Stephenson says. “They created beauty, and above all they persevered and were proud.”

To tell the stories of the people of her region, Stephenson stepped behind the camera and relied on the talents that had taken her around the world. She made documentary films about Rosenwald Schools, which educated rural Black children during segregation, as well as a documentary about women who work in chicken processing plants in eastern North Carolina. Other documentaries and screenplays are in the works, all of them highlighting challenges that have either been overcome or are still being faced.

Like any successful director looking for the best angles and working to make a production as seamless as possible, Stephenson is most comfortable being off camera, outside the glare of the lights.

“I like to be behind the scenes,” she says. “I want other people to shine.”

She also wants to make connections between the people and the organizations of Hertford County so they can support one another. In 2016, Stephenson opened Cultivator, an independent bookstore that quickly became a community hub. “We also sold local art and pottery, screened movies, held meetings and educational workshops,” she says. The store was the only bookstore within an hour’s drive in any direction but, as is the case with so many independent bookstores, it was tough to make ends meet. The pandemic made the venture even more difficult, and Cultivator closed its doors in April 2020, but the books — most of which were either donated or left behind after Stephenson’s mother, a voracious reader and book collector, passed away in 2014 — remained.

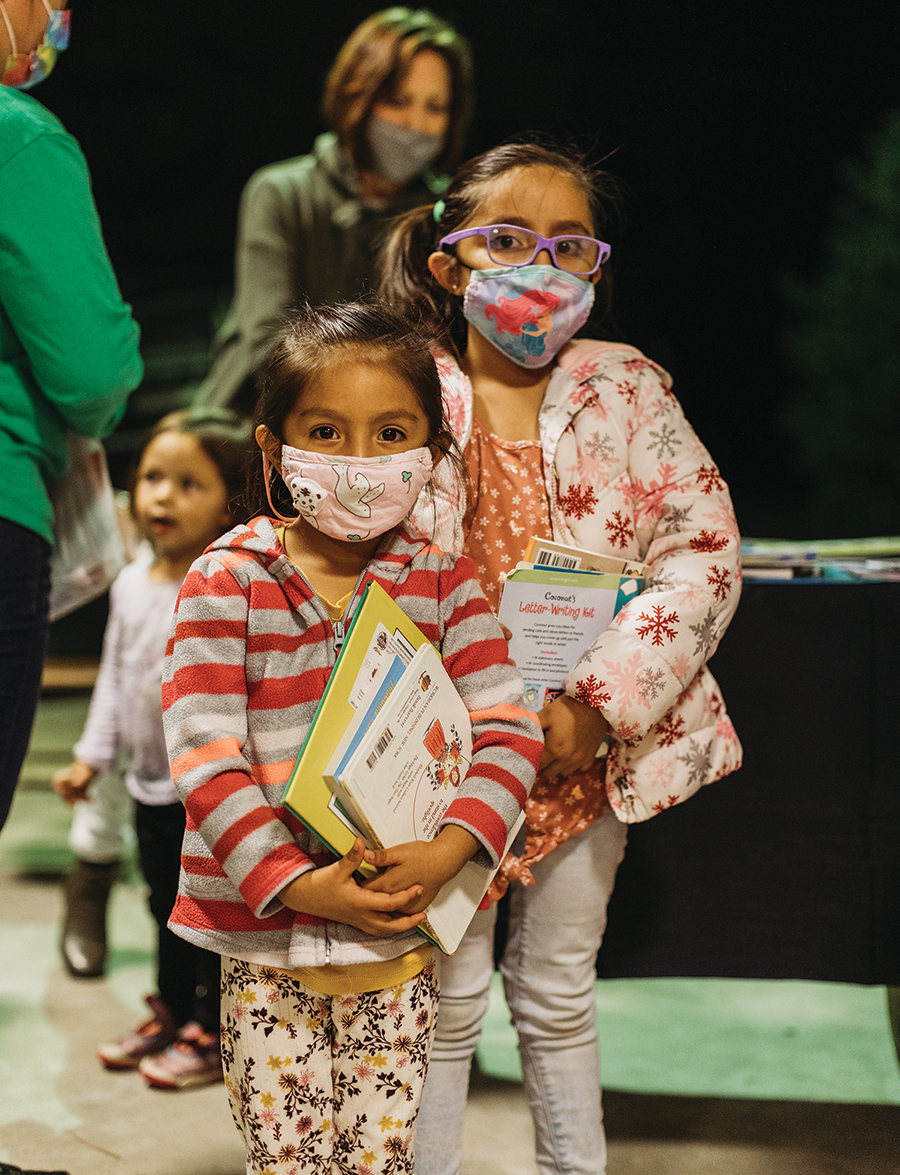

Stephenson quickly realized that not having a storefront did not have to stop the work of Cultivator, and so she converted her minivan into a bookmobile. “It’s just a folding table, personal protective equipment, and boxes and boxes of free books,” she says. “But we now serve more people than we served with the bookstore.”

The Cultivator bookmobile regularly sets up in front of libraries, grocery stores, big box stores and churches. Sitting behind a table in the parking lot of Murfreesboro United Methodist Church one chilly night in late October, a volunteer named Christina is handing out books at the church-sponsored monthly bilingual dinner. Young children, many of them Spanish speakers, tote armfuls of children’s books, some written in Spanish. When Stephenson’s name comes up, Christina, who has been a volunteer for 10 years, pauses.

“Caroline is who inspired me to get involved in the community,” she says. “She does for others.”

Andrew Brown owns a family farm with his daughter, Sharonda, and has partnered with Cultivator to address food insecurity in the community. Sharonda is the evening’s featured speaker. The family has also been the subject of one of Stephenson’s documentaries.

“Caroline got things going when she came back home,” Brown says. “You need someone like her to bring people together.”

Inside the church’s fellowship hall, tostadas and accompanying fixings are being placed on long serving tables as a line of hungry diners forms. A woman named Alejandra announces that dinner is ready. Pastor Jason Villegas greets everyone, moving quickly between English and Spanish.

“I met Alejandra at an ESL (English as Second Language) class at Cultivator,” Pastor Villegas says. When Alejandra joined Villegas’ congregation, she encouraged him to preach in Spanish to reach more people in the community. The community dinners began not long after.

When Pastor Villegas says the blessing, he prays first in English, then translates it to Spanish.

“Thank you that we have connection and unity here,” he says. He keeps his eyes closed, but he lifts his hands as if gesturing toward the people around him. “And thank you to Caroline Stephenson for bringing so many of us together.”

Of course, Stephenson is not there to hear this prayer or witness her community’s gratitude. She is overseas on a film set, operating where she is most comfortable, behind the scenes. PS

Wiley Cash is the Alumni Author-in-Residence at the University of North Carolina-Asheville. His new novel, When Ghosts Come Home, is available wherever books are sold.