When blocks of ice were the size of Volkswagens

By Tom Bryant • Illustration by Gary Palmer

“Actually, pine trees were the reason peach orchards, as we knew them in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, went away.”

It was 1997 and we were sitting in a semi-circle in the living room of Clyde Auman’s home listening to him reminisce about the old days of peach farming. The “we” was the latest crop of the Moore County Leadership Institute, a group of about 15 diverse residents of the county. Sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce, our group met once a month to tour a place important to the success of our county. It could be a historical location like the Bryant House, or something as integral to our economy as its peach farmers. Mr. Auman was, without a doubt, the patriarch of peach farming. His orchards were famous throughout the state.

“Yes, sir,” Mr. Auman continued, “before the loblolly and longleaf pines got so tall, the frosty winds of early spring would blow right on through the orchards not harming the peaches. But then the tall pines stopped the circulating winds and allowed frost to settle, and that killed not only the current crop, but later even the trees.

“Right now, on our farm, we do just about as much with pine straw as we do with peaches.” He chuckled. “Can’t make it on one end, we try it on the other. We have a few peach farmers, here and yonder, but nothing like the heyday when the region was known throughout the country.”

Mr. Auman was in his 80s when he spoke with us and, as we left his house to get on the bus and head back to Southern Pines, I hung back from the group.

“You might remember my father,” I said to him as we stood at the back door of his home.

“Who is your father?” he asked.

“Monroe Bryant. He was superintendent of the ice plant in Aberdeen.”

“I do remember him. A good man. I hope he’s doing all right. I’m sure he’s retired by now.”

“Unfortunately, Dad passed away at an early age.”

The folks had boarded the bus and were waiting on me.

“He thought a lot of you and your peaches.”

“I’m sorry to hear about your dad. He and his ice plant played a tremendous part in our peach industry. We need to get together. Come back out sometime and let’s visit.”

When I got back on the bus I sat behind the driver. On our way out to the main road, he looked over his shoulder at me. “You got along well with Mr. Auman,” he said. “Must have some history there.”

“Yeah, he knew my father back in the day when peaches were king.”

“Your dad in the peach business?”

“In a way. Without the ice plant my dad ran, the peaches would have had a hard time getting to the markets up north and out west.”

By now two or three of our group had tuned in to our conversation. One asked the natural question. “What’s an ice plant? I’ve seen those ice boxes beside the road but surely that’s not it.”

I tried to give a short history of an industry that’s as extinct as the dodo bird.

“Think about a giant cooler,” I said, “one about the size of a football field and about eight or 10 stories high full of blocks of ice, each weighing between 350 and 400 pounds. That ice was used to cool down railroad cars carrying fruit from our region, like peaches, or vegetables from down in Florida, all heading north or west.”

“And that giant cooler is no longer there?” one of the ladies asked.

“Yep, just like the old iceboxes before electric refrigerators. That’s kinda what happened to the ice plant when refrigerated rail cars came along. It was the tallest building in the county until it burned down in the late ’60s.”

I thought about that conversation the other day when I rode by the dirt lane that used to lead to the ice plant. I was on the way back from Burney’s Hardware and decided to take a walk down the railroad tracks to see if I could find the former site of the plant.

I parked out of the way next to a vacant lot, locked the car and headed south. It was only about a half mile walk and I made it in no time. Tall longleaf pines were growing where the major ice storage room used to be, and the hole in the sand that was the engine room was thick in weeds and briars about head high. I stayed on the tracks and did a cursory inspection of the remains of the place that played such a major part in my early years.

The recollection of those days came back clearly. My dad was the head honcho of all the doings around the massive plant, and I remembered my own participation in what has turned into a dead industry.

City Products Inc., the corporate head of ice plants from Miami, Florida, to Aberdeen, North Carolina, had massive ice factories in Florida, including Miami, Belle Glade, Lakeland, Sanford and Jacksonville. There was also a plant in Florence, South Carolina. The Aberdeen location was the last stop on the way north and west. The locations of the ice plants were built close to major railroad switching yards, at just the right distances, to service the needs for massive freight requirements of railroads hauling perishable fruit and vegetables across the country.

As a young fellow, I naturally hung out with Dad as much as I could, and he often let me accompany him as he made the rounds of the peach packing houses in Moore County and the surrounding area. For me, it was fun — I got to eat all the peaches I wanted. Then, as I grew older, it provided much-needed college funds. I worked a couple of summers at the location in Aberdeen and later spent a summer at the plant in Lakeland, where Dad became manager after the Aberdeen plant was closed.

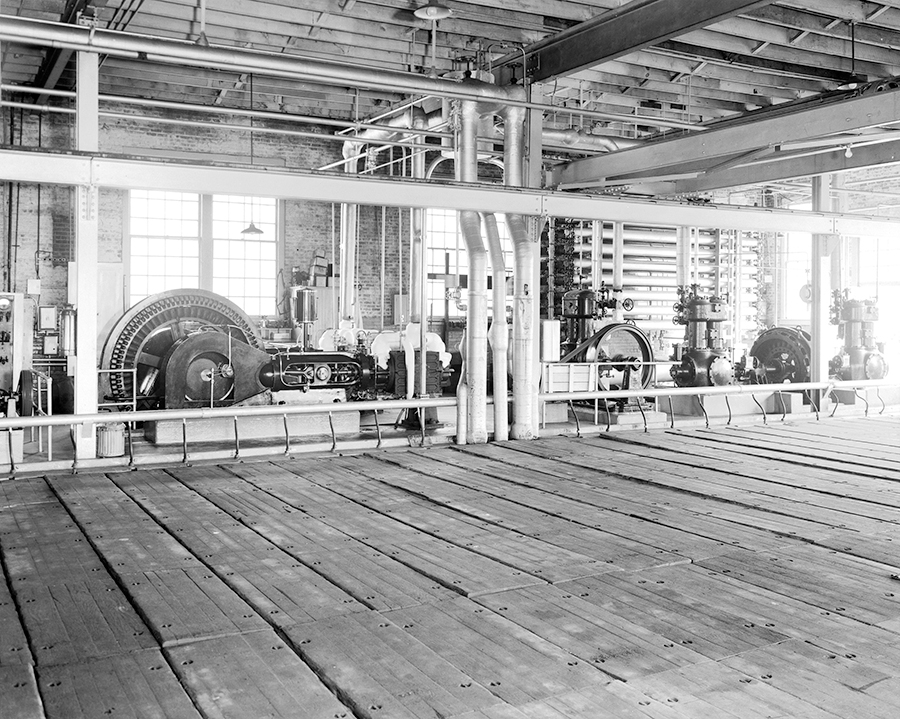

Often when summer employment came up among friends, I’d try to explain my job pulling ice. The ice was made in attached cans that would hold enough water to make a block that weighed 400 pounds, sort of like the ice in an ice tray. The cans were submerged in a refrigerated brine tank about half an acre in size. The metal cans were attached, 10 to a group. My job was to hoist the ice out of the tank, using a crane, and walk the cans down to a 10-foot dip tank, full of water, which would free the frozen cubes from the cans. Then, still using the crane, I’d lower the cans, now with loose ice blocks, to a swivel tray that would allow the ice to become free and slide on a conveyor into the storage room. I didn’t know what boredom really meant until I began pulling ice all day. But, hey, the job paid minimum wage — a dollar an hour — and that went a long way to provide spending money for college.

It’s remarkable how well the entire network of plants from Florida to North Carolina meshed to refrigerate rail cars traveling with highly perishable vegetables and fruits.

The plant was built in 1928 and the business was huge during the height of the Great Depression, when there was no shortage of laborers. Each plant location had bunkhouses, kitchens and dining halls to house traveling workers who would move as needed from one location to another following the rail cars north.

Platforms running parallel to the railroad tracks enabled workmen to ice 50 railcars at a time using just the right formula of ice and rock salt to cool the fruit or vegetables to the correct temperature and get them to their destination fresh and unspoiled.

Not long ago someone asked me what I remembered most about the ice plant. I guess it would have to be the immensity, the sheer monumental size of the major storage room, the huge electric motors that pulled the compressors that cooled and refrigerated the brine tanks and ice storage rooms, and in its heyday, the number of people it took to make it all work — and how few it took to close it all down.

Most of all, I remember my father. The endless hours he committed to making sure everything was done just right, never, ever doing things to just get by. He led by example, and I’m a better man for the experience of working with him.

Now the ice plant is just a hole in the sand where tall pines grow. The memories are all that’s still eight stories high. Most folks don’t even know it existed.

But it was here and what it did made a difference. In the process it even taught one kid about the world of real labor, sweat, the value of a dollar, and responsibility. A pretty cool job. PS

Tom Bryant is a Southern Pines resident, a lifelong outdoorsman and, in his youth, a reliable summer employee.