THE LADDER

The Ladder

Fiction and Illustration by Daniel Wallace

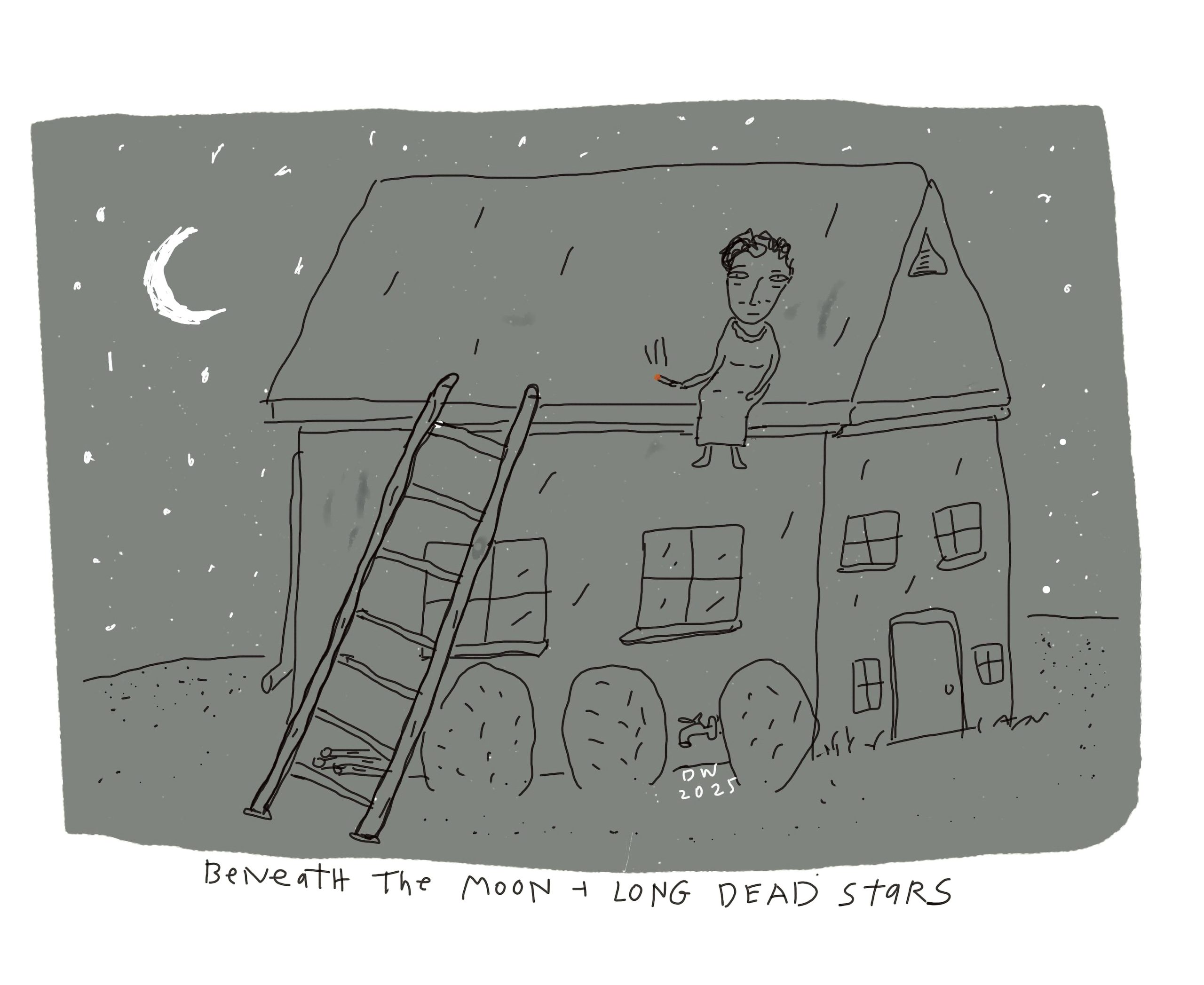

She kept the ladder hidden against the far side of the house, on its side, behind an array of shrubbery and a small pyramid of partially charred firewood. It was a metal ladder, and heavy, yellow and blue, and picking it up involved several challenging moves — lifting, leaning, pushing, and prying it into its sturdy inverted V. Harder now than ever but still doable. The hinges adjoining the two sides of the ladder sometimes stuck, and with her bare hands she had to thwonk them until they were perfectly straight. The meaty part of her palm had been pinched more than once during the course of this procedure; her Saran Wrap-thin skin roughly torn like a child’s scraped knee. All this happened at night, in almost complete darkness, the only light from the dim bulb in the laundry room, casting a soft, milky glow through the dusty windows onto the thorny leaves of a winterberry. Once the ladder was open she shook it, made sure the ground was level. Usually she’d have to adjust it, moving the legs this way and that a few times before it felt secure. Then she climbed, step by step, testing her balance on each flat rung, falling into a worry that made her take special care not to slip or get her slacks caught on anything. It was especially dangerous when she got to the very top, where it was written in serious, Ten Commandant letters: THIS IS NOT A STEP. Here there was a sharp metal protrusion, the final test that she had, so far, nimbly passed. She got on her knees on the step that wasn’t, and with her forearms on the shingles drug herself onto the sloping edge of the roof, turned herself around, and sat breathing. She brushed the dirt off her forearms. Another breath and she was fully there.

This is what she did for her cigarette, the only one she allowed herself, once a night every night, for almost all her adult life. She didn’t even have to hide it anymore, because there was no one here to secret it from. But it had become a part of who she was, a tradition she could not and would not and did not want to end until she couldn’t make the climb. It was necessary. It was her spot, her perch. There was no great view to be had, really, just the cross-the-street neighbors, a young couple in the modest, red-brick split-level, their lives ahead of them, as they say, as if all our lives weren’t ahead of us, some just farther along than others. Sometimes she could see them — the Shambergers? — as they moved from room to room, miniature people, busy as little ants. It was like watching a movie from a thousand feet away.

She smoked, and the smoke rose and quivered from the red and orange coal into a dreamy cloud, then off into a dreamy nothing. But most of the smoke was inside her, in her lungs and her blood. It made its way to her brain and she felt lighter, lighter. She felt like she could follow the smoke if she wanted. The cigarette didn’t last very long, never as long as she wanted it to, but always time enough to review the plot points of her life, the highlights, good and bad, the husband and the children and now the grands, the cars, the planes, the ships, the glam, and the struggle, the love, the sex, so much of it really it didn’t seem fair that one woman should have it all. So much. But every night she climbed the ladder’s rungs and sat here, here on top of the world, smoking, she wondered what it meant that out of all of it, out of every single second she remembered, this was the best, the very best, the moment she lived for, surrounded by the invisible world beneath the moon and long dead stars, sharing her own light with the dark.