Letter From an Enchanted Hill

And life-changing leaps of faith

By Jim Dodson

For Christmas, my clever wife gave me a pair of expensive boxer shorts that claimed to be “nothing short of life-changing.”

The gift was the result of a running joke between us. During the consumer melee that is the holiday shopping season, you see, she was amused by my reaction to half a dozen TV spots and radio commercials that claimed their products were “life-changing.”

My short list of disbelief included a magical face cream that can allegedly make you look 30 years younger in less than two minutes, an expensive brain supplement that can supposedly restore failing memory to youthful vigor, and a luxury mattress so “smart” it can cure snoring and calculate your annual earned income credit.

Funny how times have changed. And here I thought it took things like falling in love, surviving a crisis, awakening to nature, taking the cure, making a friend, finding faith or discovering a mentor to change a life. Anytime I hear an ambulance or happy news of a baby being born, I think “someone’s life is changing.”

Looking back, my life has been changed — I prefer to say shaped — by a host of people, events and moments both large and small.

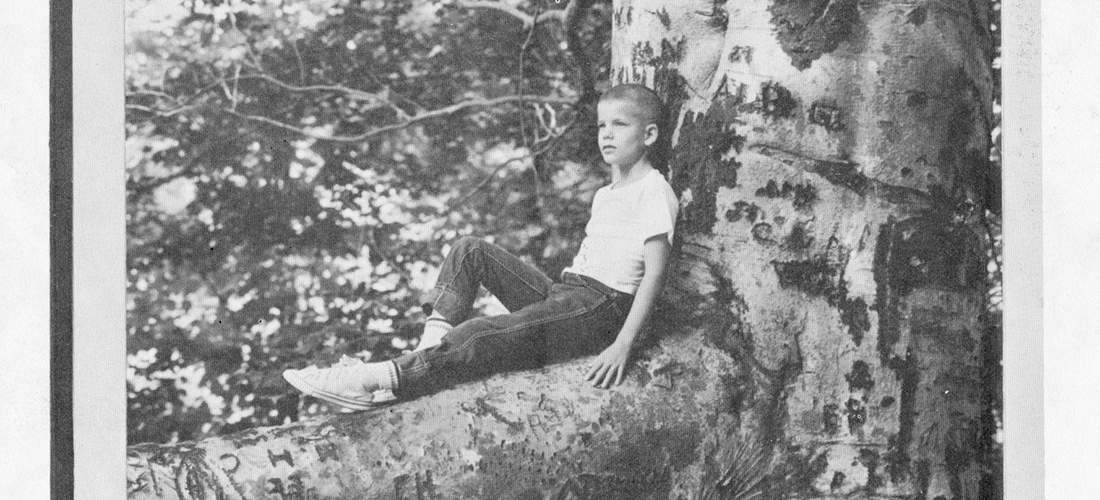

One example that stands out early was my old man’s passion for history and the lessons of nature, which probably explains why both my older brother and I became history nuts as well as Eagle scouts. History and nature, Dad believed, were life’s finest teachers, the reason he brought along a small satchel of classic books on our early camping and fishing trips in order to share bits of timeless wisdom from his favorite poets and philosophers by a blazing fire. This was his version of the Athens School, a campfire Chautauqua. It’s also why I took to calling him “Opti the Mystic.”

“All history is personal,” Opti liked to say, “because someone’s life is being changed. We grow by learning to pay attention because everything in nature is connected — including people and events.”

He illustrated both points powerfully on a cold February day in 1960 when Opti unexpectedly turned up at our new elementary school to spring my brother and me from class. We’d only been in town since the week before Christmas, barely enough time to acquire public library cards and reconnoiter the neighborhood on bikes. But we sensed that one of his entertaining field trips was in the offing, possibly a romp through the nearby battlefield where General Greene’s ragtag army gave Lord Cornwallis and his redcoat army all they could handle.

Instead, a short time later, we wound up standing near the “colored” entrance of the Center Theatre across the street from the F.W. Woolworth building in downtown Greensboro, where four brave young men from A&T State University were attempting to peacefully integrate the all-white lunch counter, an event regarded today as a defining moment in the birth of the nonviolent American Civil Rights movement.

“Boys,” he told us, “this is living history. This isn’t just going to change the South. It’s going to change America.”

The date was February 2, my seventh birthday as it happens, and Opti was right — though that change has yet to be fully realized more than half a century later.

A few days before my birthday this month, my daughter Maggie turned 30. She’s a senior copywriter for a major Chicago advertising firm and a gem of a writer with a bright future, a chip off her granddaddy’s block.

The summer after Mugs (as I call her) turned 7 in the aftermath of a divorce neither of us had seen coming, she and I and our elderly golden retriever took a two-month road trip around America, a fly-fishing and camping odyssey to the great trout rivers of the West. We rode horses, frightened a few stunning cutthroat trout, met a host of colorful oddballs and characters, lost the dog briefly in Yellowstone, blew up the truck in Oklahoma and generally had the time of our lives. I eventually put these adventures in a little book called Faithful Travelers that is still in print two decades later and closest of my books to my heart.

One night, sitting by a campfire on a remote mesa near Chaco Canyon, in a state that calls itself the Land of Enchantment, my precocious companion wondered why her old man had never bothered to write her a letter offering thoughts and advice the way she knew Opti had done for me many times in life. Just days before, she’d written me a letter thanking me for taking her on the trip.

When she and Amos the dog turned in, I tossed another log on our signal fire, sending up a spiral of embers to the gods of Enchantment, reached for a pen and paper bag and jotted the following letter from the heart to my wise and faithful fellow traveler. Every year around our shared birthdays, I take out that letter and read it just to remind myself how all history is personal and everything really is connected in nature.

Dear Maggie,

I’m sorry I’ve never written you a letter before. Guess I goofed, parents do that from time to time. I know you’re sad about the divorce. Your mom and I are sad too. But I have faith that with God’s help and a little patience and understanding on our parts, we’ll all come through this just fine. Being with you like this has helped me laugh again and figure out some important things. That’s what families do, you know — help each other laugh and figure out problems that sometimes seem to have no answer.

Perhaps I should give you some free advice. That’s what fathers are supposed to do in letters to their children. Always remember that free advice is usually worth about as much as the paper it’s written on and this is written on a used paper bag. Even so, I thought I would tell you a few things I’ve learned since I was about your age. Some food for thought, as your grandfather would say.

Anyway, Mugs, here goes:

Always be kind to your brother and never hit. The good news is, he’ll always be younger and look up to you. The bad news is, he’ll probably be bigger.

Travel a lot. Some wise person said travel broadens the mind. Someone wiser said TV broadens the butt.

Listen to your head but follow your heart. Trust your own judgment. Vote early. Change your oil regularly. Always say thank you. Look both ways before crossing. When in doubt, wash your hands.

Remember you are what you eat, say, think, do. Put good things in your mind and your stomach and you won’t have to worry about what comes out.

Learn to love weeding, waiting in line, ignoring jerks like Randy Farmer.

Always take the scenic route. You’Il get there soon enough. You’ll get old soon enough, too. Enjoy being a kid. Learn patience, which comes in handy when you’re weeding, waiting in line, or trying to ignore a jerk like Randy Farmer.

Play hard but fair. When you fall, get up and brush yourself off. When you fail, and you will, don’t blame anyone else. When you succeed, and you will, don’t take all the credit.

On both counts, you’ll be wiser.

By the way, do other things that make you happy as well. Only you will know what they are. Take pleasure in small things. Keep writing letters — the world needs more letters. Smile a lot. Your smile makes angels dance.

Memorize the lyrics to as many Beatles songs as possible in case life’s one big Beatle challenge. Be flexible. Your favorite Beatles song will probably always change.

Never stop believing in Santa or the tooth fairy. They really do exist. God does too. A poet I like says God is always waiting for us in the darkness and you’ll find God when it’s time. Or God will find you.

Pray. I can’t tell you why praying works any more than I can tell you why breathing works. Praying won’t make God feel any better, but you will. Trust me. Better yet, trust God. Breathe and pray.

Always leave your campsite better than you found it. Measure twice, cut once. If all else fails, put Duct tape on it.

Don’t lie. Your memory isn’t good enough. Don’t cheat. Because you’ll remember.

Save the world if you want to. At least turn it upside down a bit if you can’t. While you’re at it, save the penny, too.

When you get to college, call your mother every Sunday night.

Realize it’s okay to cry but better to laugh. Especially at yourself. If and when you get married, realize it’s okay if I cry.

Read everything you can get your hands on and listen to what people tell you. Count on having to figure it out for yourself, though.

Never bungee-jump. If you do, don’t tell your father.

Make a major fool of yourself at least once in life, preferably several times. Being a fool is good for what ails you. We live in a serious time. Don’t take yourself’ too seriously. Always wear your seat belt even if I don’t.

Remember that what you choose to forget may be at least as important as what you choose to remember. Someone very wise once said this to me — but I can’t remember who it was or exactly what it means.

Admit your mistakes. Forgive everybody else’s.

Notice the stars but don’t try to be one. Always paint the underside first. Be kind to old people and creatures great and small.

Learn to fight but don’t fight unless the other guy throws the first punch.

Don’t tell your mother about this last piece of advice.

Learn when it’s time to open your mind and close your mouth. (I’m still working on this one.) Lose your heart. But keep your wits.

Be at least as grateful for your life as I am.

Despite what you hear, no mistake is permanent, and nothing goes unforgiven. God grades on a curve.

One more thing: Take care of your teeth and don’t worry about how you look. You 1ook just fine. That’s two things, I guess.

Finally, there’s a story I like about an Indian boy at his time of initiation. “As you climb to the mountaintop,” the old chief tells his son, “you’ll come to a great chasm — a deep split in the Earth. It will frighten you. Your heart will pause.

“Jump,” says the chief. “It’s not as far as you think.”

This is excellent advice for girls, too. Life is wonderful, but it will frighten you deeply at times.

Jump, my love.

You’ll make it.

Love, Dad

For the record, my fancy new boxers didn’t change my life. They are quite comfortable, in fact. PS

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.