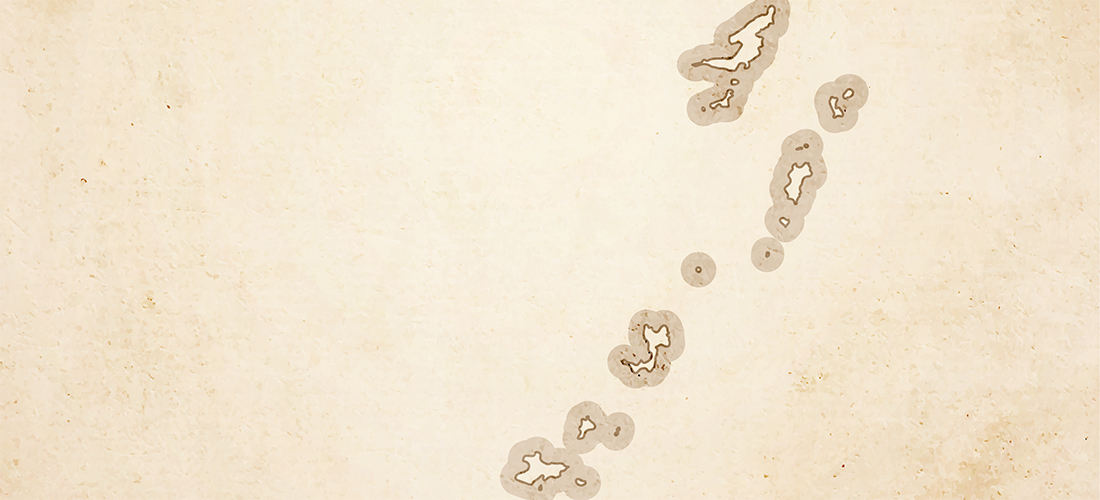

Map Fragment, on Clay

Who first thought of scratching here and there

on soft clay, instead of only giving

directions, must have wanted to keep close

the shape of all that lay between himself

and someone whose absence turned regular days

and nights into a vast terra incognita, a blank

that his mind filled with terrifying beasts, winged

serpents, who sang of other courses, other

islands, other ways. If he drew the place

he knew, and those distant places he thought

he knew, he could touch the map where she was

and say to himself, without leaving home,

if she is not here, she is there.

— Millard Dunn

Millard Dunn is the author of Places We Could Never Find Alone