My Life of Crime

Confessions of a petty thief

By Janet Wheaton

It began and ended in the summer of 1962. I was a skinny, freckled child of 10 when we arrived on the base in late January of that year and moved into a red brick, three-story apartment building, one of several in a cluster surrounded by snowy woods and rolling hills. My father, mother and I were still grieving the loss of my older sister, who’d passed away two-and-a-half years before in the bedroom across the hall from mine, following a long battle with cancer. I remembered little about that time, and what I did remember I could not bear to articulate.

Even before becoming an only child, I was an introvert, a hybrid variety that growing up military often produces: self-reliant and independent, but always looking to make that special new friend.

For a while, I thought that might be Denise. With curly dark hair and quick brown eyes, she sparkled with fun that winter morning when she plunked herself down in the seat next to me on the school bus. And — as well as a friend — I could use some fun. On weekends we took to the woods, careening down trails on our sleds, weaving between the trees and toppling into snowbanks. We hung up our sleds when spring arrived, bringing with it frequent rains that kept us indoors playing Clue on her bedroom floor. One afternoon in early May, a great volley of thunder seemed to announce the return of the sun. Temperatures climbed daily, and Denise and I grew restless waiting for the swimming pool to open.

Time never passed so slowly. On our treks down the winding road to the Post Exchange and movie theater, we paused at the pool complex, nestled into the side of a hill, to check the progress of the water flowing from giant hoses into the big concrete basin. When Memorial Day weekend finally arrived, we were up and out early Saturday morning, our new swimsuits rolled up in beach towels and tucked under our arms, our thong sandals slapping the pavement.

After a quick change in the locker room, we scampered down the steps and hurled ourselves into the deep end of the sun-dazzled pool and — in shock — scrambled back out of the frigid water just as fast. But not for long. Denise had a plan: We would stand under the cold shower for as long as we could take it, then jump into the pool. It worked — for a minute or so, the water felt warm by contrast. We were able to swim a length or two before we had to climb out and rub ourselves dry while the blood returned to the tips of our blue fingers and toes.

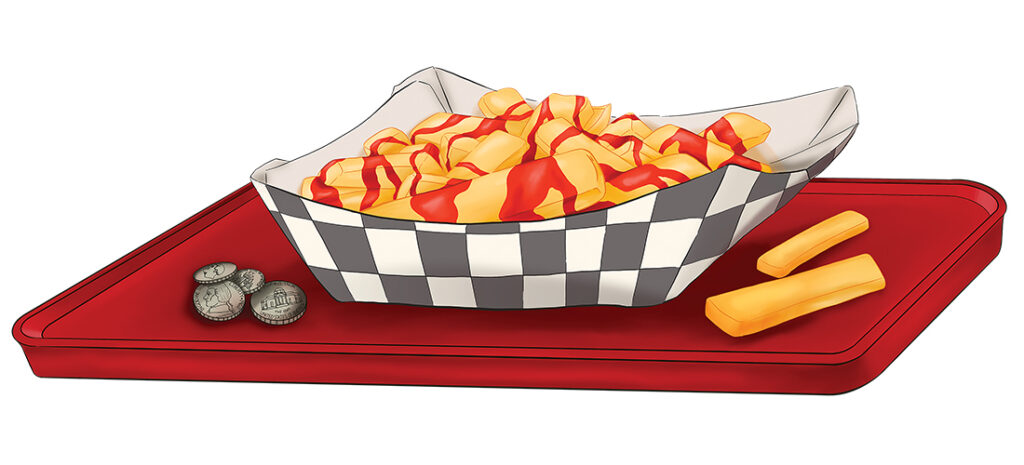

Wrapped in our towels, we headed to the snack bar, where the aroma of potatoes frying in sizzling fat awakened in me a hunger long gone dormant. When I became the only one sitting at the dinner table between my parents, I lost all desire for food and any pleasure in eating it. But that day, as Denise and I waited in line clutching purses heavy with coins, I couldn’t remember ever craving anything the way I craved those french fries.

Under a big red umbrella, we slathered our hot fries with ketchup and devoured them, two and three at a time. After wolfing down that first carton, my resurrected taste buds cried out for more. We got back in line and ordered another round. This time we carefully dipped each fry into our well of ketchup and savored the crispy outer layer, then the warm, mealy center, sharing not so much as a crumb with the sparrows scavenging under the wrought-iron table. Afterward, we beached by the pool for an hour. A sense of well-being settled over me as I lay beside my friend, the sun toasting my backside and the concrete warming my full belly.

After school let out in June, Denise and I went to the pool almost daily, tossing the brown-bagged lunches made by our mothers into the trash barrel at the gate. Economizing to make our money last, we drank water instead of soft drinks and limited ourselves to a single order of fries each day. By the end of the month we could afford only one carton between us, and we divvied up the fries as if they were precious jewels.

Come the first of July, our allowances made us flush once more. The water was warmer and we stayed in the pool longer, making us even more ravenous when we got out. Too often we splurged on two orders of fries apiece. Between that, our Saturday matinees, and PX-candy habit, we were bankrupt by the third week of the month. Denise’s dad refused her request for an advance, and I dared not ask mine. My father, a tall, barrel-chested lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps, had been a fighter pilot in World War II and Korea. Our household was clearly under his command, and I feared that approaching him about my allowance might be regarded as insubordination.

Broke and with no chance to restock our coin purses before the first of the month, Denise and I tried to distract ourselves by jumping off the high dive, doing flips off the low one, and playing Marco Polo with other kids from school. But it only made us hungrier. Forced to settle for the lukewarm sandwiches and fruit slices our mothers provided, we grew churlish with each other and envious of the people with plastic trays laden with burgers, soft drinks, and those plump, aromatic, golden fries.

As we changed in the locker room, I noticed Denise eyeing a couple of women who laid their clothes on a shelf in their lockers, hung their purses on a hook, and closed the doors. Nobody ever locked anything. Down by the pool, she was silent as we settled in a shady corner. Six weeks of lying in the sun had given her a walnut tan. I was a rash of new freckles and peeling sunburned skin. Propped on her elbows, my friend glanced over her shoulder, then looked back at me.

“Those ladies . . . ,” she said. “They wouldn’t miss a dime or two.”

“You want to ask them for money?”

Asking was not what my friend had in mind. No, we would simply help ourselves. “They’ll never miss a few coins,” she insisted.

“That’s stealing. And if we get caught we’ll get in a lot of trouble.”

“Who’s gonna get caught?”

No way, I told her. But as morning turned into a french fry-less afternoon, her proposition began to seem less and less criminal. Walking home later on, we put together a plan: Denise would go into the lockers; I would be the lookout.

We committed our first heist the following morning, and it went off without a hitch. After entering the locker room together and changing into our swimsuits, we futzed around until the room was empty. Then Denise lingered inside near the lockers, and I dawdled outside the door while she carefully extracted a dime from one pocketbook, two nickels from another, until she’d collected enough for two orders of fries. If anyone approached the locker room, I yelled our coded alert: “I’m going down to the pool!”

My taste buds were initially unconcerned with the method by which they’d been satisfied, and those ill-gotten fries settled happily in my stomach that first day. And the second and third. But on day four I was dragging a fry around in my ketchup when a woman stopped at our table.

“Excuse me, girls,” she said. I caught my breath. “If you aren’t using this chair, may I borrow it?”

“Sure,” Denise said with her easy smile, but I found it hard to meet the woman’s eyes. As she settled with her two kids at a nearby table, I couldn’t stop thinking that it might have been her money that paid for the fries I’d been eating.

“I don’t want to do this anymore.” I pushed my half-eaten carton away and laid the rest of my pilfered coins on the table. “You can have these.” Denise stared across the table at me as she chewed. Then she shrugged and scooped the coins into her hand.

“Yeah, OK,” she said, her tone changing when she added, “but you can’t ever tell anyone.” I promised I wouldn’t and left her there alone.

I stayed away from Denise and the pool for the next few days and took long walks alone in the woods behind our building, debating with myself exactly how much the word of a thief was really worth. Not much, I finally decided and mustered the courage to go to my parents and confess.

They were shocked, and I could imagine what they were thinking: Your sister would never have done such a thing! No, my sister, beautiful, smart, honorable, and beloved by everyone, including me, would never have taken a penny that didn’t belong to her — not for anything, and certainly not for a stupid slice of potato. That daughter was gone, and I was what they were left with. A thief. My mother sank down onto the couch and begin to cry. My father ran a hand around the back of his neck, cursing under his breath, and sent me to my room.

When I was summoned back half an hour later, he was sitting in his chair. “Come over here, Pumpkin,” he said, using the nickname I hadn’t heard in a long time and pointing to a nearby chair. He told me they were disappointed by what I’d done, but proud that I’d come to them. There was no way to give the money back since we didn’t know who the victims were, so there was nothing to be done — except to give me a lecture about honesty and integrity and to detail the dire consequences had we been caught. He agreed to say nothing to anyone, not even Denise’s parents — if I promised never to do such a thing again.

It wasn’t necessary for my father to forbid me to hang out with Denise, but he did. The pool and movie theater were off limits too. I suffered my sentence without complaint and spent my remaining summer afternoons at the base library, reading books from the adult shelves. I’d turned 11 that August and wasn’t feeling much like a child anymore. PS

Janet Wheaton taught herself to type on a second-hand manual typewriter that her father gave her at the age of 10, and she hasn’t stopped writing since. She lives in Pinehurst with her husband, Bill, and is working on a memoir in essays.