NC SURROUND SOUND

Sounds of a City

Music with a connection to place

By Tom Maxwell

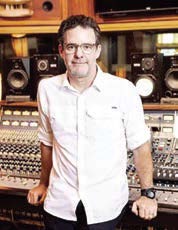

Alex Maiolo is a creature of pure energy. It’s not that he talks fast or acts nervous — he’s simply an ongoing conversation about electronic music, geography and whatever else happens to capture his interest. He’s also a singular kind of globetrotter, one who doesn’t sound pretentious about it. He loves Estonia’s capital, Tallinn, so much he made music with the place, a 2021 conceptual performance he called Themes for Great Cities.

Conceived as one of his two main pandemic projects — the other was getting better at making pizza — the musical idea took on a life of its own even as the flatbread faded. He invited Danish musician Jonas Bjerre, Estonian guitarist and composer Erki Pärnoja and multi-instrumentalist Jonas Kaarnamets to collaborate. What resulted was something that felt improvised, unpredictable and exhilarating.

“Even though I was living in Chapel Hill, I was trying to think about, well, what do you miss when you miss a city?” he says.

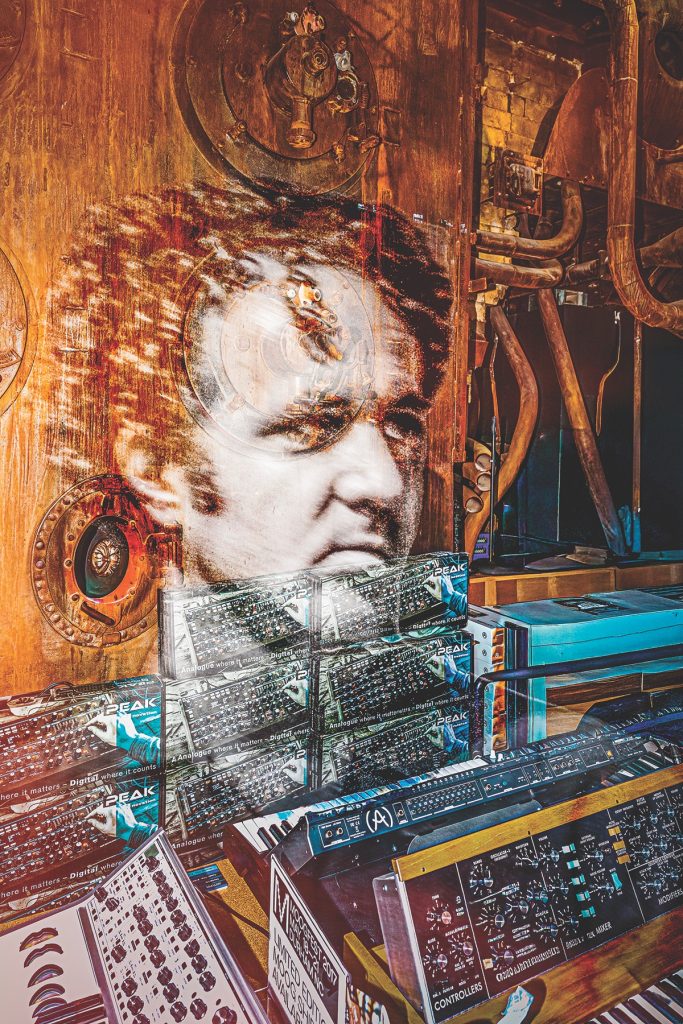

The obvious things — favorite restaurants, familiar streets — were only part of it. Beneath that, Maiolo sensed a deeper, subconscious connection to place that might be expressed musically. He seized upon the idea of treating the city itself as a collaborator. “I wanted to write a love letter to this incredible city by gathering elements of it and assembling them in a new way,” he says. Sounds and light readings became voltages; voltages became notes. “Every synthesizer is just based on the assemblage of voltages,” Maiolo says. “So, if you have voltages — particularly between negative five and plus five volts — you can make music.”

The group collected source material across Tallinn: gulls shrieking overhead, rainwater rushing down a gutter, chatter in a market, the squeak of trams, cafeteria trays clattering at ERR (Estonia’s equivalent of the BBC). A custom-built light meter called the Mõistatus Vooluringid — “mystery circuit” — captured flickering light and converted it into voltages. These inputs were then quantized, filtered and transformed into sound. Tallinn became what Maiolo called “our fifth band member. And just like with any band member, you can say, ‘Hey, that was a terrible idea’ or ‘way to go, city — that was a good one.’”

From the outset, the goal was to create something that felt alive. “We wanted happy accidents,” Maiolo says. “Quite frankly, I wanted to be in a situation where something could go wrong.” Unlike a pre-programmed, pre-recorded synthesizer session, Themes for Great Cities was designed to court risk through completely live and mostly improvised performance — to create the same adrenaline rush that test pilots might feel, only with much lower stakes. “No one was going to crash,” Maiolo says.

That philosophy made the project’s debut even more dramatic. Originally slated for a 250-seat guild hall built in the 1500s, the show was suddenly moved to Kultuurikatel, a former power plant that holds a thousand. Then came another surprise: The performance would be broadcast live on Estonian national television, with the nation’s president in attendance. “It was far beyond anything I had imagined,” Maiolo admits. “I thought we were going to play to 30 people in a room.”

Visuals by Alyona Malcam Magdy, unseen by the musicians until the night of the show, added a surreal dimension. Estonian engineers captured the performance in pristine quality. “It all came together,” Maiolo says. “The guys I was doing this with are total pros.” The recording was later mixed and pressed to recycled vinyl at Citizen Vinyl in Asheville. Unable to afford astronomical mailing expenses, Maiolo split 150 LPs between Estonia and the United States, carrying them in his luggage.

Though imagined as a one-off, Themes for Great Cities continued to evolve. The group returned to Estonia in 2022 for a new performance in Narva, reworking parts of the score and staging it in a former Soviet theater. “We didn’t record that one because it was similar to the first. But when we do Reykjavik, we’ll record that one and hopefully release it,” he says. Yes, Iceland looks like the next destination. The plan is to work partly in the city and partly in the countryside, where light, landscape and weather can all feed into the music.

The ensemble has grown tighter, but Maiolo emphasizes the lineup will be flexible, with an eye toward incorporating local musicians. Vocals may be added in future versions, perhaps improvised or even converted into voltages to manipulate the electronics. “Anything is possible,” he says.

Though he now lives in San Francisco, Maiolo continues to think of North Carolina as part of his creative geography. He still has his house in Chapel Hill, stays connected to Asheville’s Citizen Vinyl, and carries his records home through RDU.

Maiolo and his partner of seven years, Charlotte, are to be married in Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. Her father, a German who came of age during World War II, once spent a year in San Francisco immersing himself in jazz. Even now, as he struggles with dementia, he plays clarinet and listens to Fats Waller and Oscar Peterson. The sense of music as a lifelong companion, capable of anchoring memory and identity, is yet another thread running through Maiolo’s work.

Ultimately, what began as an experiment has become an ongoing series of collaborations. Each city brings its own textures, rhythms and surprises. Each performance is both a portrait and a partnership. “At the end of the day, it just kind of sounds like music,” Maiolo says nonchalantly, as if jamming with an entire city is an everyday thing.