ART OF THE STATE

Pete Sack’s Second Act

Taking a turn as community leader

By Liza Roberts

A successful painter for nearly 30 years, Pete Sack has work featured in several corporate collections, including SAS Institute and Duke University Hospital. His resume includes dozens of prominent solo and group exhibitions and he’s currently got a waiting list for commissions.

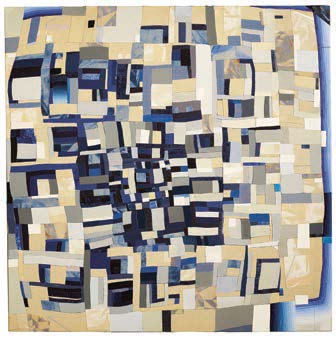

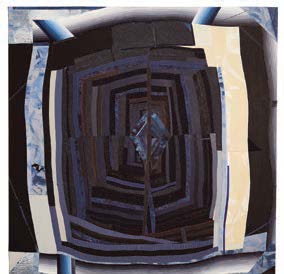

Known for paintings that feature finely nuanced portraiture through an abstracted lens, Sack often obstructs faces with shapes and colors, combining pencil drawings with watercolor and, finally, oil paint. Sometimes two or three portraits of the same person are layered on top of each other, just enough expertly wrought detail to recognize who it is.

His completely abstract paintings are no less contemplative. Thought Patterns is a series “created with the premise that we begin every day as a new person,” he says. Depicted as layers of spheres and ovals of various hue, some are cool and moody, others buoyant, a few bright and jangled. The resulting paintings reflect the moods and thoughts of the days he made them. “Each day we are reacting to fresh thoughts, actions and environments,” he says. With a limited palette and the self-imposed requirement that he complete each piece within a single day, the works are “fully representative of a particular moment in time and take into account the deeply layered experience each individual has with the present moment.”

Sack’s path began at the Visual Art Exchange — a nonprofit hub for nurturing, connecting and showcasing artists — when he landed in Raleigh in 1988 after earning his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at East Carolina University. “When I moved here, the VAE was where you learned how to be an artist in this area,” Sack says. It’s also where he and many others had their art exhibited publicly for the first time. “It was where you got your pieces on the wall.”

An emerging artist residency at Artspace and a full-time studio there followed, which further engaged him with the downtown art community. When the creative space Anchorlight opened on S. Bloodworth Street, he moved his practice there. Then he spent nearly five years as an artist in residence at SAS Institute in Cary, where he made as many as 150 works of art for the growing software company’s walls. These days, Sack has a studio on Hargett Street and a dedicated roster of collectors.

None of it happened by sitting back and waiting for things to come to him. For years, Sack worked to create opportunities for himself, finding creative ways to get his work seen outside the gallery system, including working with real estate developers and interior designers making art that he could be proud of while still suiting their purposes.

The spirit of those efforts expanded to the wider community in 2023 when he and three other established Raleigh artists, Jean Gray Mohs, Lamar Whidbee and Daniel Kelly, began convening groups of fellow artists to discuss the declining number of exhibition opportunities and spaces to gather and experiment downtown. The result was the creation of The Grid Project, an art collective focused on mounting pop-up exhibitions. With the long-term loan by ceramic artist Mike Cindric of his former studio (now called Birdland), The Grid Project has mounted 10 shows in the last two years, exhibiting work by 25 artists. Those exhibits spawned the creation of what Sack and Mohs call the Boylan Arts District.

The calling on everything Sack’s learned over the last 27 years about what it means to be an artist in his community.

In an unexpected turn of events, Sack was tapped last spring to co-direct the Visual Art Exchange with Mohs. The two aim to revive the 45-year-old institution, bringing it back to its roots as a resource for artists, a place for them to learn the practical business of being an artist, connect with other artists, and show their work.

A rebirth is in order, because among other challenges, the pandemic hit the VAE hard. By one estimate cited by Sack, the nonprofit gave out as much as $300,000 in funds directly to support artists during that time. The financial hit proved significant, and the organization moved out of its brick-and-mortar home in late April as a cost-saving measure. Sack and Mohs were recruited by the board and took the reins in June.

“As we move into this new chapter, our immediate focus will be on strengthening the internal structure of the organization,” the co-directors said in an October email to stakeholders. At the time, they were full-time volunteers; the VAE had just $7,000 in the bank. They have since held a series of listening sessions to gather input about the organization’s future direction.

“We need to temper expectations,” Sack says, “and let people know that this is the reality. But we aren’t going anywhere. We’re going to see this through.”

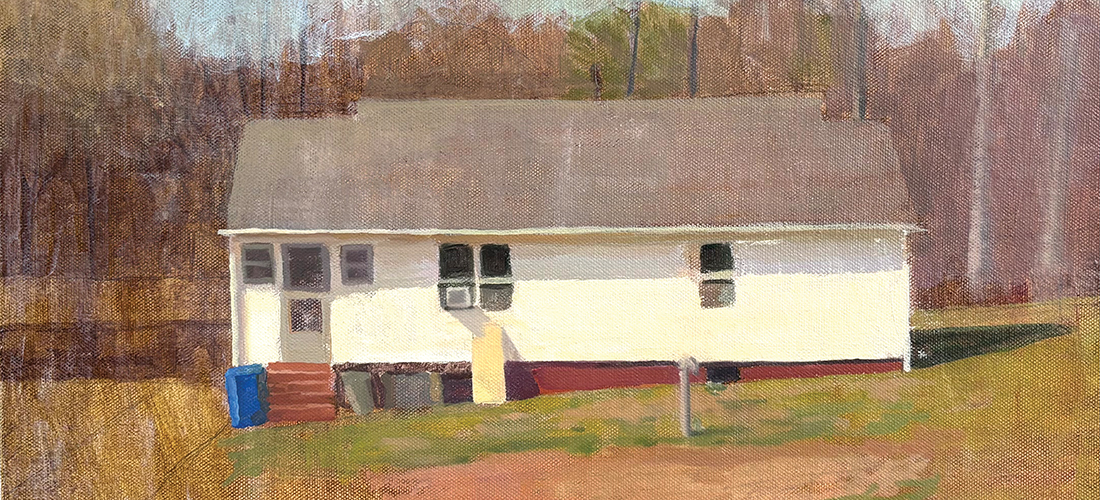

In the meantime, they’re doing what they can, where they are, with what they’ve got. In October, they filled the empty windows of the former CVS at the corner of Hargett and Fayetteville streets with art by Renzo Ortega and Lee Nisbet, working with Empire Properties to turn what was a dark corner into an art beacon. VAE is providing small stipends for the artists and calling the effort “StreetFrame.” Sack says they hope to replicate it in other empty downtown storefronts.

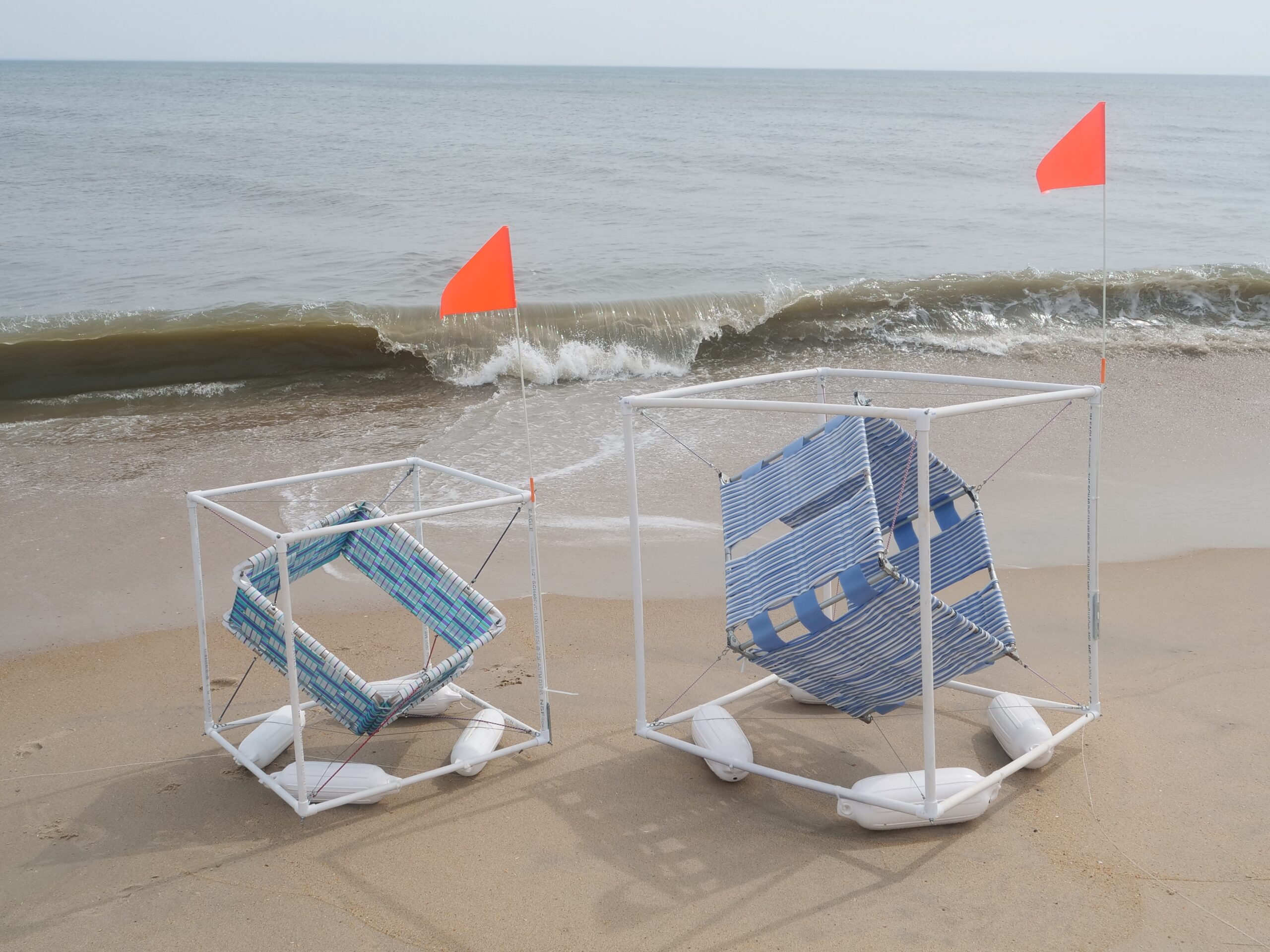

In October, under the VAE banner, the duo opened Echoes of Modernism, an exhibition examining how modernist architecture shapes our political, social and economic lives. Curated by artist Sam van Strein, it included work by Amba Sayal-Bennett, Daniel Rich, Frances Lightbound and van Strein.

Meanwhile, Sack’s art has its own demands. Last year, he had back-to-back shows for six months at a stretch and worried about “saturating” the market.

The demands of his work with VAE have given him time to “take a step back, to recalibrate” his art, and to think about where to take it next. “My sketchbook is filling up, I am building up the reserves, and I’m excited to see where the work goes,” he says. “Toggling between the figurative and the abstract is still something that I’m pushing. At the end of the day, I’m always going to be an artist. I’m building up to something bigger.”

And despite the obvious challenges, that same spirit is fueling his work with VAE. Sack says he’s determined to make it indispensable to the next generation of Raleigh artists.

“Years ago, I would never have thought I’d be in this position, just because it’s not something I ever wanted to do,” he says. “But the writing is on the wall that nobody’s coming to save us. We have to save ourselves.”