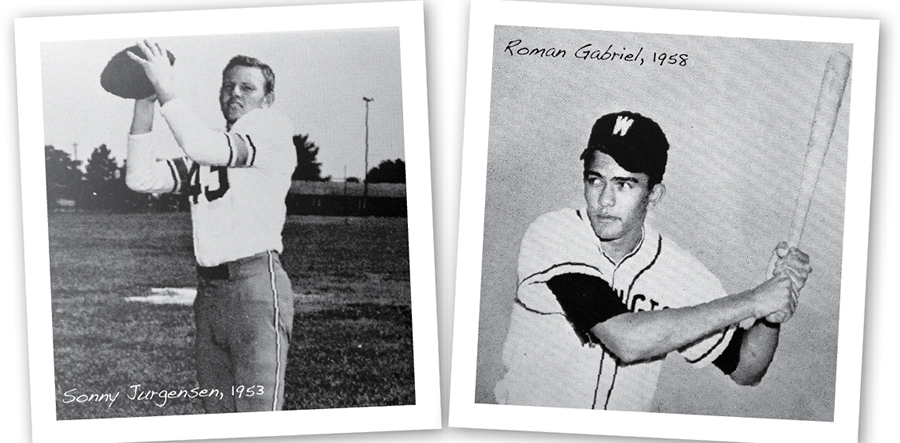

How Wilmington’s legendary coach, Leon Brogden made superstars of a couple hometown heroes

By Bill Fields

It’s been 63 years since Sonny Jurgensen graduated from New Hanover High School, a very long time by any measure, but the Pro Football Hall of Famer hasn’t forgotten the mood of his happy days.

“They were fun times, they really were,” Jurgensen says, his accent still as soft as taffy on a beach blanket. “Lively crowds at home. A bus on the back roads to the away games. Raleigh, Durham — you did a lot of traveling. And Coach Brogden really was a special guy.”

They are in their late 70s or early 80s now, and for other men from other places, such a distant chapter might be a cloudy memory. For the boys who suited up in orange and black, who were Wildcats under legendary Leon Brogden in the 1950s, when prep athletics were king in Wilmington and fans packed the bleachers for home games in basketball and football, the recollections tend to come easily.

“We didn’t have television in Wilmington until 1954,” says Ron Phelps, 84, a member of the Wildcats’ 1951 state champion basketball team. “If you wanted to enjoy sports, you went to Legion Stadium on football Friday nights or to the gym in the winter. When we came out in our basketball uniforms, the crowd got rowdy. They’d stomp their feet in the balcony and scream and yell.”

Jurgensen, 82, was in New Hanover’s Class of 1953, a three-sport athlete who left the Port City to attend Duke and was a star quarterback in the National Football League for the Philadelphia Eagles (1957-1963) and Washington Redskins (1964-1974). Regarded by many as the best pure passer in NFL history, Jurgensen — full name Christian Adolph III — threw for 32,224 yards and 255 touchdowns in his career.

“Every pass that man threw fit the situation,” one of Jurgensen’s receivers for the Redskins, Jerry Smith, said upon his NFL retirement. “Fast, slow, curve, knuckleball, 70 yards, 2 inches — they were always accurate. If it wasn’t completed, it wasn’t No. 9’s fault.”

Not only did Jurgensen emerge from Wilmington in the post-World War II period and go on to achieve NFL success, so did Roman Gabriel, 76, who graduated from New Hanover High School in 1958. Starring in football, basketball and baseball for the Wildcats as Jurgensen had, Gabriel was quarterback at N.C. State and then enjoyed a lengthy, successful NFL career for the Los Angeles Rams and Philadelphia Eagles, earning NFL Most Valuable Player honors in 1969.

Jurgensen and Gabriel might not have achieved what they did without the influence of Brogden, an NHHS institution from 1945 through 1976 and the first high school coach to be inducted into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 1970. Proper and placid, Brogden, who died at age 90 in 2000, did not have to shout to be heard.

Brogden dressed up when he coached — always coat and tie (and hat on the gridiron) unless he was on the baseball diamond — but didn’t dress down his charges. “If we ever lost a game, he took the blame, and if we won he gave us the credit,” says Jimmy Helms, a 1958 NHHS graduate. “He was really more of a father image. He was a legendary coach but an even better man. You just wanted to please him so much. If you messed up and he was looking down at the floor because he didn’t want to see what he just saw, that was worse than being slapped.”

In an era during which teenagers tended to mind their elders, Brogden made a lasting impression on the students he was around. “To me he was just like magic,” says Jackie Bullard, another member of the Class of ’58. “He was probably the calmest, most respected person I’ve ever been around. It’s hard to explain how much that man meant to me. He coached hard without raising his voice. When he spoke, everything was quiet.”

Bill Brogden, the middle of Leon and Sarah Brogden’s three sons, who recently retired after a long career as a college golf coach, also played on two (1960, ’61) of his dad’s eight state championship basketball teams. “You wanted to play for him, and you didn’t want to disappoint him,” Bill says. “He had your respect, and when he asked you to do something, you didn’t ask why, you just did it.”

Although he did plenty of it, winning wasn’t everything to Brogden. “You hear today you’ve got to win or you’re a nobody,” says Gabriel. “With Coach Brogden, it was not about winning or losing, it was how much you enjoy preparing to do the best you can. And that carries over to your schoolwork, your whole life. If you enjoy it, you’re a winner.”

Brogden won quickly after arriving in Wilmington following a nine-year stint at Charles L. Coon High School in Wilson, winning the state basketball championship in 1947, the Wildcats’ first North Carolina title in 18 years. The city’s population grew to 45,000 by 1950, a 35 percent increase over a decade in part because of the shipbuilding during the war. That meant a lot of ball-playing kids would eventually play for Brogden and his assistant, Jasper “Jap” Davis, a star fullback at Duke whom Brogden coached in Wilson.

“You had so many kids,” Jurgensen says. “We all played. There were guys everywhere.”

Jurgensen, whose family operated Jurgensen Motor Transport, a trucking company that carried freight for A&P, grew up on South 18th Street about a mile from New Hanover High School. “Our neighborhood had about 30 boys within a four-block area, and we always had enough kids to make up any kind of game we could think of,” Thurston Watkins Jr. wrote in a 2004 Star-News article. “One day a red-headed kid with a big smile asked to play ball with some of us out in front of his house on a big empty corner lot. Sonny was the name of that red-headed kid.”

When boys graduated from pick-up games to organized leagues, Brogden wasted no time having an impact on them. “He would recognize guys in junior high who looked like they were going to be good athletes or good people and take them under his wing,” says Bill Brogden. “He had the junior high school coaches run his system so when kids got to high school everybody would know what was going on.”

Jurgensen noticed the continuity when he got to New Hanover. “We practiced all the fundamentals, starting when I played freshman ball,” Jurgensen says. “When you made varsity, it was the same system, which was good. But coach would adjust the offense according to what kind of players we had. We ran the Split-T and a Spread at times.”

Few details escaped Brogden when it came to preparing his players. Jurgensen developed the snap in his throwing arm — and Gabriel also developed a powerful motion — through drills in which the quarterbacks would pass kneeling and sitting. “He’d have you sit on your fanny because it forced you to turn your waist and strengthened your arm,” Gabriel says.

In Jurgensen’s junior season (1951), he was a valuable running back and linebacker for the Wildcats, while Burt Grant — who would go on to play at Georgia Tech — quarterbacked the team. During a 34-0 win over Wilson, Jurgensen scored two rushing touchdowns and recovered a fumble, made an interception and blocked a punt. Jurgensen always had a knack for the big play.

“One of the first times I saw Sonny,” says Bullard, “we were watching New Hanover play Raleigh one Friday night. I must have been in the sixth or seventh grade. We kicked off to Raleigh and they ran it back 90 yards for a touchdown. When Raleigh then kicked off to us, Sonny returned it a long way for a touchdown. It was 7-7 and I bet only 30 seconds had gone off the clock.”

With 10,000 spectators watching at Legion Stadium, New Hanover beat Fayetteville 13-12 in a battle of undefeated teams in 1951 to win its first Eastern Conference title since 1928. The following week the Wildcats beat High Point 14-13 to win their first football state title in 23 years.

The Wildcats couldn’t repeat as state champs in 1952, but Jurgensen starred at quarterback and earned All-State honors. That school year, the “Most Athletic” senior averaged 12 points a game for the basketball team and played third base and pitched for the baseball Wildcats, batting .339.

“Sonny had that big flashy smile. People idolized him,” Helms says. “He was so natural about anything he did, and he was a great basketball player. Coach would tell about when Sonny made nine shots in a row and never saw a one of them go in the basket. He knew it was going in when he shot it, so he turned and went back down the court.”

When Jurgensen was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1983, Brogden told the Star-News: “I will always remember Sonny for his competitive spirit and unusual good sense of humor. He had the ability with his personality and skills to raise the level of play in his teammates and also to stimulate his coaches. Associating with Sonny was not quite like traveling with a big brass band, but you did realize you were with someone special.”

While Jurgensen went to Duke — where he played quarterback on a team that passed infrequently and was in the defensive secondary — Gabriel was getting noticed back home for his multi-sport talents. Not as outgoing as Jurgensen, Gabriel had a personality a lot like their coach. “Roman was very serious, very humble,” says Helms. “He was the most unselfish fellow you’ve ever seen and a terrifically hard worker.”

Says Bullard, a co-captain with Gabriel in football and basketball and a close friend: “He had a lot of Coach Brogden in him. He wasn’t ‘Rah-rah, look at me, I’m Roman Gabriel.’ He was just a leader who brought everything to the table, and he expected everybody else to bring it to the table too.”

Gabriel inherited his ethic from his father, Roman Sr., a native of the Philippines. “He went straight to Alaska to can salmon to make a living,” Gabriel says of his father’s early days in the United States, “then he got into Chicago, where he became part of the railroad.”

Roman Sr. was a cook and waiter for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad after moving to Wilmington where he, his wife, Edna (an Irish-American from West Virginia), and Roman Jr. lived in the working-class Dry Pond section of the city in an apartment complex that had been built for shipbuilders. “My father and three other Filipinos who worked with him were probably the only Filipinos in North Carolina at that time,” Gabriel says. “He had a saying, ‘Never let an excuse crawl under your skin.’ That meant that because of who you are, you might have to work a little bit harder. And if you’re not willing to work hard, you don’t deserve to be good. He wasn’t an athlete, but he was probably the best cook and waiter the Atlantic Coast Line had outside of the other three Filipinos.”

Because his dad loved baseball, Roman Jr. did too, getting tips as a young boy from a former major leaguer who lived nearby, George Bostic “Possum” Whitted. Brogden noticed Gabriel when he was a 10-year-old Little Leaguer, and the boy developed into a high school first baseman who could hit for power, slugging a 500-foot home run in a game at Fayetteville that old-timers still talk about. By the time he got to high school, basketball had become his top passion.

With Gabriel a key factor, the Wildcats won the state hoops championship in 1956, ’57 and ’58 and captured the state AAA baseball crown in ’56 and ’57. Twice they were N.C. runner-ups in football. Jurgensen came back to visit his former team. “When I was in high school, Sonny would come out to practice and help Coach Brogden and Coach Davis a little bit,” Gabriel remembers. “I’ve never seen anybody who could throw it like Sonny, a tight spiral every pass.”

Gabriel and his teammates in the different sports logged a lot of miles riding in the school’s well-used athletic bus. “We thought we were going to have a wreck because Coach Jap would drive and Coach Brogden would sit behind him and have a conversation,” Gabriel says. “He would be driving the bus with his head turned talking to Coach Brogden.”

“We took turns sitting in the back,” says Bullard, “because you always got a little nauseated from the fumes.”

Bothered by asthma as a child, Gabriel grew into a 6-foot-3, 200-pound force on the field and court after a growth spurt and summer of working with weights going into his senior year at New Hanover.

“Roman got to be a big guy for high school as a senior,” says Bill Brogden. “He was hard to handle inside on the basketball court.”

Gabriel proudly points out that he out-jumped a 6-9 Durham center on an opening tip-off, and his athleticism was enhanced by the coaching acumen of Brogden. “He did a lot of studying, and he tried to figure out how to win,” Bill Brogden says. “He was always drawing some kind of play on a napkin. He was so into his job, it was like he was way before his time.”

The Wildcats’ three straight basketball championships during Gabriel’s NHHS years were helped by the team’s use of Brogden’s innovative spread offense, which North Carolina coach Dean Smith credited as an inspiration for the famed Four Corners that he began using successfully in the early 1960s. Brogden tweaked his tactic a bit, depending on the makeup of his team. A formidable rebounder, Gabriel was also a good lob passer to Bullard.

“It was pretty much the Four Corners, and we won the state championship playing it,” says Bill Brogden. “If you had a good ball handler and were a good free-throw shooting team, nobody could beat you. They couldn’t catch up.”

Before Army football flanker Bill Carpenter became well-known as the “Lonesome End” during the 1958 and ’59 seasons, Wilmington utilized a similar ploy. “Howard Knox, our No. 1 receiver, lined up way out near the sideline,” Gabriel says. “He and I had hand signals. He didn’t come back to the huddle on certain plays.”

Ten years after Gabriel’s final fall wowing the faithful at Legion Stadium, on Oct. 22, 1967, he squared off against Jurgensen in a Rams-Redskins contest at the Los Angeles Coliseum — the first time the two faced off in the NFL. Brogden flew out to watch, dining with Gabriel the night before and having breakfast with Jurgensen on game day. As if ordained by the man each admired so much, who watched a half from each side of the stadium, the game ended in a 28-28 tie.

It is one of Gabriel’s favorite memories of Brogden, but here’s another.

Gabriel had read that Boston Celtics star Bob Cousy smoked a cigar to relax before a big game. On the morning of the 1958 N.C. state championship, Gabriel bought five cigars for the Wildcat starters gathered in his hotel room. A knock on the door, and it wasn’t room service.

“What are you doing smoking cigars?” Brogden asked.

“Ask Gabe,” Bullard said.

“Coach,” said Gabriel, “I saw in a sports magazine where Bob Cousy smokes a cigar to relax before a big game, and you know how successful the Celtics are.”

“If it’s good enough for Bob Cousy, it’s good enough for my boys,” Brogden said. “But don’t get sick.” PS