At the height of the Jim Crow era, little Jackson Hamlet’s Ambassadors Club hosted R&B and rock ’n roll’s greatest stars

By Bill Case

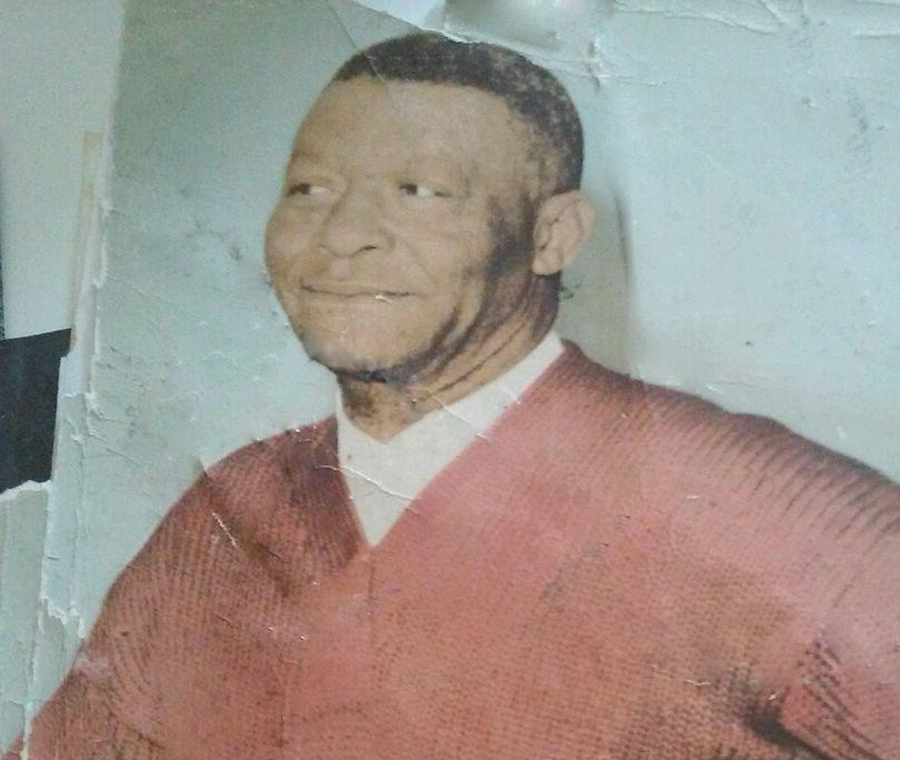

Maybe there had been some trouble with the law back in Georgia. Maybe there’d been a fight and someone died. Could be that’s why he hightailed it out of the state and made his way to the Sandhills in the 1920s. And maybe that explains why the strapping 6-foot-5, 250-pound John Nelson began using another name — Sam Arnette. One thing was certain: If he was a fugitive, Moore County was the ideal place to live on the lam, since law enforcement was only a sometime thing. Whatever the murky circumstances of Arnette’s past, he made his presence felt in the African-American enclave of Jackson Hamlet, sandwiched between Aberdeen and Pinehurst.

When Sam arrived on the scene, the community’s several hundred residents provided a significant portion of the workforce serving Pinehurst’s renowned resort. Maids, caddies, cooks, gardeners and waiters all called Jackson Hamlet home. The paychecks may not have stretched very far, but they were going to be spent somewhere. If a person of brown or black skin color fancied a bite to eat in a restaurant, however, that was a problem. In North Carolina’s mid-20th century segregated society, blacks were not welcome in any bar, restaurant, or other public accommodation where whites were present.

Black businessmen filled the void. Tiny pocket stores providing groceries and other necessities popped up in Jackson Hamlet. In the late 1930s, Sam Arnette embarked on his own entrepreneurial voyage, opening a combination filling station and restaurant on the Aberdeen-Pinehurst Road, now N.C. 5. Sam’s Cafe became a favorite meeting spot for folks swapping gossip and family news while dining on fried chicken and pork sandwiches cooked by Myrtle Houston, who would become Arnette’s second wife.

On Sept. 25, 1944 an earth-shattering explosion rocked Arnette’s business, breaking store windows and the glass in the gas pumps. Remnants of military blasting materials were found in the debris, and Sam suspected white officers from nearby Camp Mackall who had been refused service at Sam’s Cafe were responsible. Given what the higher-ups deemed to be inconclusive circumstantial evidence, the officers were never prosecuted.

After the war, Arnette’s cafe faced a different danger — competition. Just yards away, the House of Blue Lights opened, sporting a jukebox. For a nickel, recordings from a new wave of swinging black musicians like Billie Holliday, Louis Jordan and Joe Turner spun on the turntable. Couples strutted their stuff on the joint’s compact dance floor. Deep in the piney woods, accessed by a rutted sand path barely wide enough for one car to pass, James “Babe” Gaines operated yet another sweet juke joint he called Cabin in the Pines, and Jake Lawhorn’s Paradise Grill opened too.

Recognizing that the war’s end would cause business to boom at the resort, Arnette made a savvy investment that set him apart from his business competitors in the community. He reasoned new service jobs would mean new workers who would require new housing. When the opportunity arose to purchase a 25-acre grape vineyard across the Norfolk and Southern Railroad tracks on the eastern side of the highway from Sam’s Cafe, Arnette jumped on it. For an investment of $74 an acre, he became the land baron of Jackson Hamlet. New homes sprouted up where, even today, Arnette Street crosses the tracks into the “Arnette Subdivision.”

Sam kept two acres adjacent to the Norfolk and Southern tracks for something else he had in mind. Noting the popularity of the juke joints, he reckoned live music would have surefire appeal. Top black musicians were already performing in a network of bars, clubs and restaurants throughout the South, collectively known as the “Chitlin’Circuit.” Sam figured his land would be an ideal location to build a nightclub that could become a regular stop on the circuit. There were several African-American neighborhoods in the county to draw from, and if the area’s young ladies came, then the black soldiers from nearby Camp Mackall would likely break down the doors to join them.

Arnette’s dream nightclub, the Ambassadors Club, caught the eye of all who happened by. The building’s very design announced that this was a place where music was played and heard. Viewed from the road, the structure’s peculiar curvature at its south end gave the impression of a gigantic alabaster double bass lying strings-up on the ground.

Precise details of the club’s history are scarce. In the 1940s and ’50s the local white-run newspapers tended to ignore the goings on in areas where blacks lived, be it Jackson Hamlet, Taylortown or West Southern Pines. Fortunately, there are still some folks around old enough to remember Sam Arnette and his club.

Ida Mae Murchison, a 96-year-old resident of the Pine Lake facility in Carthage, is beset with the typical infirmities expected for a nonagenarian. But Mae’s mind remains sharp and when she talks about Sam Arnette and the club, her face lights up like a schoolgirl’s. Murchison broke the color line at the Carolina Hotel by becoming its first African-American chambermaid in the mid-1940s, but her moonlight job was as Sam’s ticket seller at the Ambassadors Club. She remembers collecting $2 a head, though the amount varied depending on the reputation of the performer. As many as 250 patrons would pay their way inside, a fire code being a quaint concept. Admission was good for a night of entertainment and dancing along with sandwiches prepared by Myrtle Houston in the club’s modest kitchen. Beer and wine could be purchased at the bar, tended by Mae’s husband, Brice. Long-time civic activist Carol Henry remembers that when a big show was held at the Ambassadors Club, “you couldn’t get in.” Cars filled the parking lot and spilled up one end of the road and down the other. Though the raised stage was large enough to accommodate the big bands of the ’40s, after the war, the combos tended to have three to five members, a trend that would have been welcomed by Sam Arnette and other club operators on the Chitlin’ Circuit. As Billboard Magazine reported, “the nut (i.e., guarantee) for a small unit is much lower than for a 20 piece band.”

According to Murchison, the dance floor was where the action was. There weren’t many wallflowers at the Ambassadors Club. Dressed to the nines — men in coats and ties, women dolled up in their best dresses — couples reveled in the acrobatic maneuvers characteristic of the popular swing dances. The better men dancers would lay down spectacular tap routines. A fringe benefit of Mae’s job was that Sam permitted her to dance the night away gratis once she’d collected the evening’s take. And make no mistake; Mae considered this a major perk. Husband Brice, was stuck behind the bar, so she danced with friends. She chuckled recalling her prolonged and energetic night of dancing with a local doctor who was so exhausted at the end of the evening he was forced to postpone a scheduled tonsillectomy the following day.

Asked whether stronger alcoholic spirits than beer and wine were illegally sold at the club, even at 96 Mae could not quite bring herself to confirm any bootleg activity went on. “I heard tell something about that,” she said demurely. Her 72-year-old son, Butch Murchison, was too young during the club’s heyday to be an eyewitness, but he doubts Sam or his father made liquor available on the premises, although he said both knew where it could be had on short notice. Virtually every restaurant and hotel selling beer or wine in Moore County had a way to find the hard stuff for thirsty customers. “Nobody felt there was anything wrong with selling liquor,” Butch recalls of the prevailing sentiment. On the rare occasion when a raid was planned by the authorities, it was not unheard of for some friendly public employee to provide advance notice of the impending bust.

Anytime young men (particularly soldiers on leave) are mixed together with women and alcohol, there is some risk of a disturbance, but the Ambassadors Club had surprisingly few. If an incident did occur, Sam was armed with a pistol. Though he never actually fired it, if the circumstances demanded he was known to occasionally employ it as a blunt instrument. Myrtle Houston packed heat too. According to another long-time Jackson Hamlet resident, Lillian M. Barner, who remembers Sam’s wife well, “You didn’t mess with Myrtle.”

Advertising acts for the Ambassadors Club was a two-man job. Arnette had taken a liking to Butch, not even a teenager yet, and the pair would drive Sam’s shiny ’53 Buick to African-American neighborhoods to tack up posters heralding the coming attractions. The tight-knit communities took it from there, spreading the news by word of mouth. Arnette made a lasting impression on his young sidekick. “Sam was totally no nonsense when it came to his business. No fooling around. When the radio was on, he always turned it to the news. He wanted to know what was going on in the world. Later, when I became involved with my own businesses, I was influenced by his example,” said Butch.

Securing the services of out-of-town African-American performers involved more than simply paying their performance fees. None of the hotels allowed blacks, so local Jackson Hamlet residents often housed the artists during their gigs. Sam’s house, across the road from the Ambassadors Club, provided extra beds for band members to crash. The Murchisons were among the families that guested musicians, and wide-eyed young Butch relished listening to tales of their adventures on the road.

Before the Chitlin’ Circuit came along, it was difficult for black artists and bands to find places to perform, particularly in the South. Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway were exceptions whose music found favor with white audiences in the 1930s and ’40s. But performers of “race music” (mainly blues and R&B) were mostly shut out from touring until black promoters and club owners in the South created enough of a network that artists could hop from town to town playing in a series of grueling one-night stands.

The business model followed by the artists comprising the mid-century Chitlin’ Circuit matches the one still motivating the music industry today. Live shows were designed to increase the demand for the performer’s recordings; the hoped-for jump in record sales would presumably cause a corresponding boost in attendance at future shows. If fortunate, a black singer might sell enough records to land a spot on Billboard Magazine’s R&B chart. But since black artists of the late ’40s and early ’50s couldn’t expect to attract large numbers of whites to their music, their prospects for major commercial success were limited. Young talents like Ruth Brown, Ray Charles, Fats Domino and James Brown barnstormed the South, playing black nightclubs and roadhouses, hoping to net a couple of hundred dollars from each gig, or at least enough to move on to the next town on the circuit. All of them performed in Jackson Hamlet at the Ambassadors Club, and all are enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The vivacious Ruth Brown became a mainstay on the circuit. When Atlantic Records released her song “Teardrops from My Eyes” in 1950, it quickly ascended to No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart. It was not long before “Miss Rhythm” was the acknowledged queen of R&B. Music critics said that in the South, Ruth Brown was “better known than Coca-Cola.” When she recorded Bobby Darin’s composition “This Little Girl’s Gone Rockin’” in 1958, the song crossed over and climbed high on the pop charts.

Florida native Ray Charles hit the circuit in the early ’50s. His piano and vocal style blended gospel, jump blues, jazz, country and boogie-woogie in a new, irresistible sound. His 1954 R&B hit for the Atlantic label, “I Got a Woman,” brought Charles to the pinnacle of that genre. “What’d I Say,” released in 1959, established the man known as “The Genius” as a pop sensation as well. Charles is well-remembered for a stand he took in the battle for civil rights. In March 1961, he balked at playing a date in Augusta, Georgia, when he learned that blacks and whites were going to be separately seated. Mae Murchison’s most vivid recollection of Charles’ appearance at the Ambassadors Club occurred in the parking lot when she witnessed an angry Ray cussing a blue streak after running his hand over a fresh dent in his sedan.

Born and raised in New Orleans, piano man Antoine “Fats” Domino first came into the public eye in 1949 with his R&B record “The Fat Man.” Later efforts like “Ain’t That a Shame” (1955) and “Blueberry Hill” (1956) became massive cross-over pop hits after more mainstream artists’ (Elvis Presley and Pat Boone) renditions of R&B music paved the way for white acceptance of Fats, Ray, Little Richard and other stalwarts of the Chitlin’Circuit. Suddenly they were being hailed as pioneers of a new form of music — rock ’n’ roll. Fats later remarked, “Everybody started calling my music rock ’n’ roll. But it wasn’t anything but the same rhythm and blues I’d been playing down in New Orleans.”

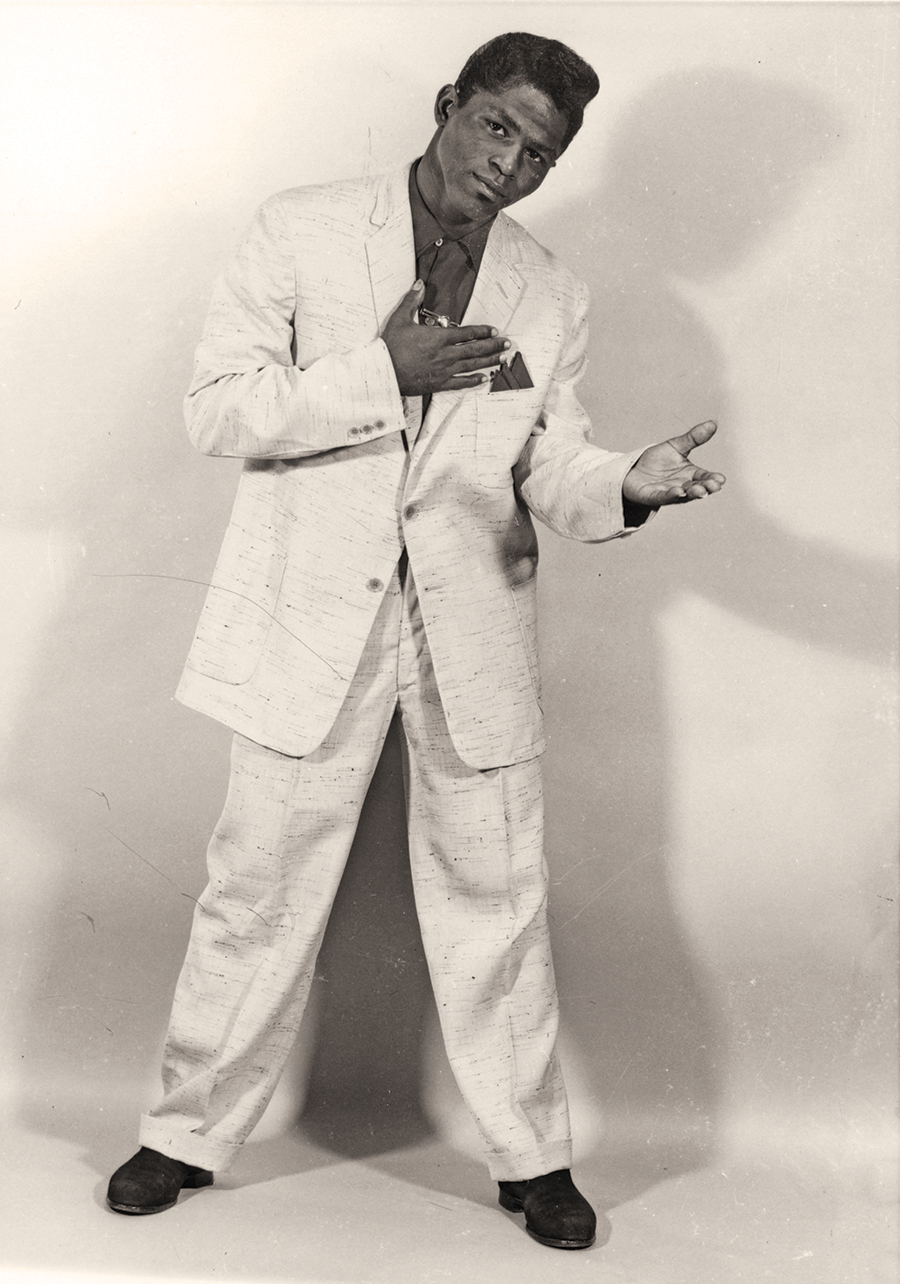

While the gigs of these greats at the Ambassadors Club were memorable, it was the electrifying performance of young James Brown and his Famous Flames that most vividly sticks in Mae Murchison’s mind. A chill went up her spine when she saw “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business” on his knees shaking off his cape and pleading for the love and attention of all the young women in the house as he belted out “Please, Please, Please” to thunderous applause. Though performers often venture into the crowd to sing, the irrepressible Brown took things one step further, leading the Flames outside the club to the railroad tracks, the audience in tow, to listen in rapture as Brown’s high-powered voice echoed through the pines of Jackson Hamlet. Given that three other joints were located just a stone’s throw away from the club, the band’s foray onto the tracks gave a number of folks the unexpected privilege of watching the unbridled James Brown in action. Talk about advertising!

Just at the time many of the club’s performers were breaking through to a wider audience, Sam Arnette died, on Nov. 28, 1954, at the age of 59. It was not long before it closed down for good. Its demise didn’t mark the end of great music in the building, however. After the club property was sold to the Jones Temple Church of God in 1962, the church conducted rousing revivals featuring performances of gospel stars like the Dixie Hummingbirds and Shirley Caesar.

After several decades, the church abandoned the property and the building was razed. A passerby today won’t find any vestige of the old club or any remembrances of the many greats who preformed there: Cab Calloway, Louis Jordan, Ruth Brown, Ray Charles, Fats Domino or James Brown. Most of the buildings that housed the other joints are long gone, too. The lone exception is Sam’s gas station and cafe on Rt. 5 at the west end of Jackson Hamlet — the one that nearly blew up in 1944. A curtain store occupies the space.

Butch Murchison believes that the heyday of Sam Arnette’s Ambassadors Club was, “the happiest time for people who weren’t happy otherwise.” All that remains is the sound of a voice high up in the pines. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.