The unquenchable passion of Jef Moody

By Bill Fields • Photograph by Tim Sayer

Most mornings between 6 and 7 o’clock, Jef Moody laces up his running shoes and goes to the starting line, a sandy trailhead next to his driveway in Taylortown. He will travel a couple of miles on paths through the pines and scrub oaks in about 45 minutes. It is, at age 63, as far and as fast as his body will allow unless he wants to move around like a much older man the following day.

He has logged 129,000 miles since he began keeping track as a child, more than half the distance to the moon or five times the circumference of Earth. “I remember once when I had gotten over 100,000, I finished my run and was sitting in the driveway and my wife (Nadine) asked me what was wrong,” Moody says. “I said, ‘I’ve run more than 100,000 miles and I feel like I did every one of them today.’”

A while back, someone called Nadine, and told her “a man was hopping down the road.” It was Jef, who says these days he goes “jopping,” a hybrid of jogging and hopping, because of the decades of wear and tear.

“I’ve got a good bad knee and a bad good knee,” he says of the arthritic joints, punctuating the description with a smile. “I wake up still thinking I can do a 4-minute mile, then my two feet hit the floor. But 90 percent of the time, the knees don’t hurt when I run unless I step wrong or go too fast. I’ve got to run slow. I hate running slow.”

Although any running is better than no running, if Moody felt differently about the pace of his current workouts, it would be a news flash. He spent the first third of his life becoming an elite cross country and middle distance runner, one of Moore County’s best all-time athletes, after moving to Southern Pines to live with his maternal grandmother, Geneva Mincer, as a fifth-grader in 1968. He was a star at Pinecrest High School and Pembroke State University (now UNC Pembroke). A member of Pembroke’s 1978 NAIA national-championship cross-country team and the 1979 NAIA 1500-meter national champion, Moody still holds eight UNC Pembroke school records, including the 800 meters (1:50.30) and 1500 meters (3:44.10) established in 1977.

“I never saw him finish a race,” says Gary Barbee, a Pinecrest cross-country teammate of Moody’s in 1972. “Jef would already have his warm-ups back on by the time I was done. He already was ‘the man.’”

During his stellar prep career, during which he was a national Junior Olympic champion in cross-country and 800 meters, Moody was recruited by 175 colleges. Kansas was among the many prominent schools to pursue him, and the Jayhawks enlisted a famous alum to make their pitch the second semester of Jef’s senior year at Pinecrest.

“My Grandma said there was a guy on the phone named Jim Ryun,” Moody recalls. “She didn’t know much about track, but she wanted to know who he was. I just told her he was a big-time runner.”

Ryun, the first high school runner to break the 4-minute mark in the mile and a three-time Olympian (1964, ’68, ’72), called Moody once a week for a month in the spring of 1975 to no avail. Pembroke coach Dr. Edwin Crain’s visits to the Moody home paid off.

By 1980, the year following his graduation from Pembroke and an NAIA national championship in the 1500 meters, Moody was a good bet to qualify at that distance for the Summer Olympics in Moscow. That dream dissolved when the United States and some of its Allies boycotted the games in protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

When the 2020 Tokyo Olympics were postponed until 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it took Moody back 40 years. He was at the wheel of his red Fiat driving through South Carolina returning home from a race when he heard about the Olympic boycott on the car radio.

“I had run a 5-miler in Columbia in 23:48, I think it was,” says Moody. “I was pretty much ready to go. The (Olympic qualifying) trials were coming up. I’d gotten my stuff for that. I was upset and decided I wasn’t going to go to the trials. When Nadine and I got married the previous November, I said to give me a year to get through the Olympics. I was crushed, but as they say, time heals.”

Moody is sitting in his “Track Shack,” a small, detached man cave/office in the shadow of the home where he and Nadine raised their children (Yarona, Jessica and Jeff II). The walls are covered with photos, ribbons, medals and uniforms — markers of Moody’s running life that began 475 miles and a world away from Moore County in a tough part of Philadelphia.

“I was 5 or 6 years old,” Moody says. “The doctor told my mom I had a heart murmur and it’d be good for me to exercise a little. She let me go out and run a little bit — run around the corner. That’s when I started to love to run.”

Moody found a kindred spirit in classmate Louis Pagano. From first through fourth grades the pair ran the half-mile to school in the morning, made a round trip at lunch and back home in the afternoon. The exercise and other hijinx — the boys rubbed the wax from Nik-L-Nip bottles on the soles of their dress shoes to slide across the playground — were a buffer against a difficult family situation. Mildred and Robert Moody Jr. separated. “My parents were apart and my mother was sick. We were homeless and it was North Philly, a rough part of the city.”

On March 3, 1968, Isaac Mincer, the uncle of Jeff (it was two f’s then) and his younger brother, Robert III, intervened. He put the children — Jef was a month or so from turning 11 years old — on a train to Southern Pines. “I was like, ‘Man, we’re leaving everything we’ve known,’” Moody says. “I remember telling my grandmother the first week that as soon as I finished high school I was out of here.”

But Moody made friends and charted a course for himself in the Sandhills, never returning North to live. Grandma Mincer’s yard with a large garden of fruits and vegetables was a stark contrast to Jef’s urban roots. “It was just a big garden,” he says, “but I felt like a farm boy.”

He soon began to immerse himself in running, motivated at first to win a live turkey in a 2-mile race for middle-schoolers held on a Midland Road horse track located where the Longleaf golf course exists now. Moody didn’t bag the bird in two tries — he laughs about ending his career with a frozen fowl-earning victory at a mid-1980s Pinehurst Turkey Trot — but developed an indefatigable work ethic to complement his athletic talent and competitiveness.

Moody’s Pinecrest coach, Charlie Bishop, an important mentor, told him to always win as convincingly as he could. And Moody trained to make that possible.

“Since 1969, I don’t think I’ve missed a hundred days of running,” Moody says. “I had two streaks of six years and ones of five and four years where I didn’t miss a day.”

And on almost all of those days, Jef — who began preferring to spell his first name that way in 1994, after someone misspelled “Jeff” in a letter — pushed himself hard.

“He always ran one more lap after practice,” recalls Pembroke teammate Jim Miles, a pole vaulter who sometimes ran relay events. “I asked him why once, and he said, ‘Jim, somebody else out there is doing it too.’”

Crain worked his distance men hard, rain or shine, a thunderstorm the only thing that paused the training. “When freshmen got to campus, they sometimes wouldn’t come to practice if it was raining,” Crain says. “Jeff would go to the dorm and tell them that wasn’t how it works. He was a great influence on his teammates.”

Nothing could keep Moody away from his passion. During his final track season at Pinecrest, he suffered a stress fracture in his right foot running an indoor race in Greensboro. For a few weeks, he had the cast removed for a meet, then replaced. During the 1977 NAIA cross-country national championship in Kenosha, Wisconsin, the 5-mile course went through some woods. After glancing back at a teammate, Moody collided full speed into a tree.

“They said I finished the race but I don’t remember,” Moody says. “I don’t remember flying home. They were still pulling bark out of my eyes when I got to the infirmary. But the next morning I snuck out the window to go on a training run. I did the run and got caught climbing back through the window.”

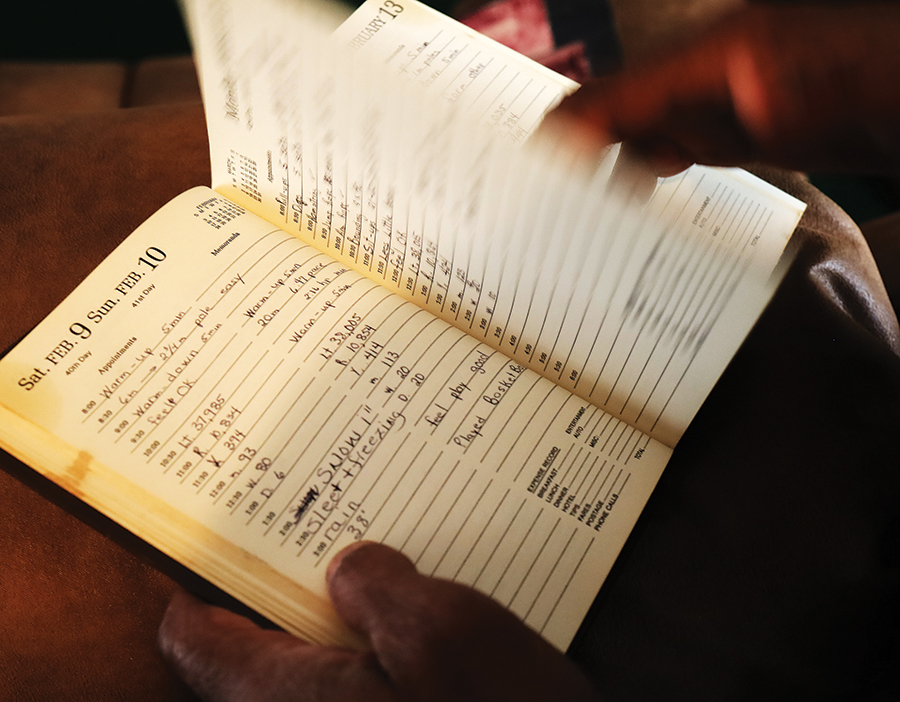

He ran a 5:30 mile in the seventh grade. In the eighth grade, he lowered his time to 4:51 after being motivated to break the school record of 5:14. As Moody got more serious about his training, he logged every workout on a calendar, a practice carried out with more detail in desk diaries and, later in adulthood, a computer. It was a habit, he discovered after his father died years later, that ran in his family.

“Going through his things, we found notes he kept on his daily life,” Moody says. “He wrote down everything he did during the day.”

Occasionally, the numbers Moody denoted in his log were staggering. As a Pinecrest sophomore, Barbee was on an activity bus making the 27-mile drive to Richmond County for a jayvee basketball game. As they passed through Pinebluff, Barbee saw Moody running beside U.S. 1. Later that evening, Barbee saw him in the stands spectating during the varsity game, having run all the way there.

Pembroke was loaded with talent during Moody’s time on the Robeson County campus. “I had 15 guys who could run five miles in 25:30,” Crain says. “If you sneezed, two guys would pass you — all the guys were good.”

Wayne Broadhead, who ran for the Braves with Moody, says, “We had to do 10 miles in under an hour just to get a uniform.”

Ten miles was a normal afternoon team practice schedule, with runners having done five miles on their own in the morning before class. Crain rode a bicycle alongside his charges as they ran, but Moody never needed much prodding. For hill work, Crain drove the Braves to a steep stretch of Hwy. 74 east of Rockingham, where they ran up and jogged back a handful of times.

“Jef didn’t miss a day of practice in four years,” Crain says. “He was a great leader, by voice and by example.”

Moody has run distances from 200 meters through a marathon. As a 128-pound high school freshman who couldn’t do a single pull-up, he tended to get jostled on a crowded track or cross-country field. He realized he needed to get stronger. “A lot of people don’t realize you can only run as fast as you can pump your arms. If you can’t pump your arms fast, you’re not going to run fast.” By his sophomore year at Pinecrest he was up to about 150 pounds. When he graduated, he could do 40 or more pull-ups.

“Remember those Michelin commercials with the tire digging into the road?” Miles says. “Most people ran on top of the track; Jef had a forceful stride that ate into the track. He could go sub-11 seconds in the 100 meters. That’s some great leg speed for a miler.”

Moody was running a time trial during a 1978 practice on the Pembroke track when he bettered four minutes in the mile for the first time. His teammate Garry Henry, a star long-distance runner, was a formidable foe and had speed too. Moody set out to just stay in front of Henry and did. “We showered and got dressed and coach told us what we ran,” Moody says. “I was 3:59.2.”

Moody’s confidence spiked when he defeated Dick Buerkle, world record-holder in the indoor mile, during a 1979 race in Georgia. Later that year he and Nadine, a fellow Moore County native, got married on the afternoon of Nov. 24 — after the groom tended to some other business in Raleigh.

“The race was 6.2 miles but I think I ran 7 because I was hustling to the car to get home for the ceremony,” Moody says.

He had begun what would be a long, successful career as an elementary school physical education instructor, guiding youngsters as Moore County educator-coaches such as John Williams, Joe Wynn and Nat Carter had influenced him, with direction and encouragement.

“Jef is definitely a people person,” says Larry Rodgers, retired UNC Pembroke track and field coach for whom Moody worked as a part-time assistant in the 2000s. “He communicates well and always has a positive attitude. The athletes really listened to him, and he always made them feel like they could reach their potential.”

As a teacher and coach, Moody always tries to connect with young people, often encouraging them to develop talents they weren’t aware they possessed.

“He’s always been great with kids because he’s still a kid at heart himself,” says Nadine.

Out of college and ineligible for the race he wanted to run more than any other, Moody was gearing up for a new school year teaching when the final of the 1500 meters at the Moscow Summer Olympics was held Aug. 1, 1980, at Lenin Central Stadium. Great Britain’s Sebastian Coe won the gold medal with a time of 3:38.4. It had required 3:43.6 to get through one semifinal and 3:40.4 in the other. The former time was just slightly better than Moody’s fastest time in the event.

In advance of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, Moody considered taking a stab at the steeplechase. He learned the requisite hurdling technique but was hampered by not having an available training partner. Moody shelved his Olympic hopes for good. “I ran in some little races here and there, but basically after 1980 my racing career was over.” He competed for the last time 21 years ago, in a 3000-meter masters run in the same city he raced the day he got married 20 years earlier.

Now a grandfather of five — “a relay team of boys and a girl,” he says — Moody continued to coach, including a stint at Sandhills Community College, where his expertise and dedication helped the Flyers succeed. It’s hard not to if you follow his mantra.

“I want to always get 100 percent out of myself,” Moody says. “That might not be my best, but it’s my best on that day.” He remains a volunteer with Sandhills Track Club, eager to help youth with the will to find a way.

“No, I didn’t get a shot at the Olympics, but I believe I’ve had a bonus of 52 years after moving down here,” Moody says. “I sit here and think about it and kind of tear up. Who knows what could have happened up in Philadelphia? It was a tough situation.”

As long as Moody can run, he will run. It is 2020 and he is on a rural path, but it could be 1965 on a city sidewalk, his lungs and legs taking him to a new place. PS