Soaring above Pinehurst in 1911

By Bill Case

Photographs by Ellsworth Eddy from the Tufts Archives

The Sandhills was abuzz with excitement after the Pinehurst Outlook reported on March 11, 1911, that within the week, an airplane would be aloft over the town. “Pinehurst,” declared the paper, “is soon to enjoy the novel sight of seeing man vie with the buzzard in its majestic journey through the clouds.”

The community had been chosen by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (now Curtiss-Wright Corporation) to host a “school of aviation instruction” from March 18 to April 5. The acknowledged goal of the school was promotion of the company’s two-winged biplane, designed by aviation pioneer and company owner Glenn Curtiss.

In addition to providing lessons to would-be pilots, curious onlookers were going to be offered “the delights of a ‘fly’” in the biplane with the “daring aviator” in charge of the school, 24-year-old Lincoln Beachey. Though he had flown planes for just over a year, Beachey’s breathtaking aerial exploits were already gaining him cult-like status among flight enthusiasts.

The native San Franciscan broke into the flight game in September 1905 when Capt. Thomas Baldwin hired the mechanically inclined, but aeronautically inexperienced, teenager to fly a dirigible at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. Beachey, piloting from a flimsy wooden undercarriage beneath the balloon, skillfully maneuvered the craft while thousands below marveled at the spectacle. According to Frank Marrero’s biography Lincoln Beachey — The Man Who Owned the Sky, Lincoln received “high-profile press coverage by landing, message in hand, on top of ‘The Oregonian’ newspaper company and City Hall, thus initiating air mail.”

Beachey revelled in this first taste of public acclaim. In pursuit of further headlines, he, along with brother Hillery, conjured up an outlandish scheme. On June 14, 1906, Lincoln ascended in a dirigible from a Washington, D.C., park, the first flight of any kind to occur in the nation’s capital. Gobsmacked by the sight of the airship as it floated high above the Mall and the Washington Monument, citizens were in an uproar. Then Beachey turned the lumbering airship in the direction of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. As he descended to the White House lawn, presidential guards sprinted toward the dirigible with mean intentions. But Beachey was in luck.

President Theodore Roosevelt’s wife also saw him arriving and chose to intervene. She restrained the guards and greeted the daring pilot.

“Congratulations, young man!” exclaimed Edith Roosevelt. “This is certainly the most novel call ever made on the White House.”

Beachey next paid a visit to a joint session of Congress, landing on the steps of the Capitol, then spending the following hour discussing the future of air travel with fascinated lawmakers. He would become an outspoken advocate for governmental investment in aviation.

Beachey’s airship histrionics brought him considerably more than his requisite 15 minutes of fame, but dirigibles became old news when public attention turned to winged aircraft and the daredevils who piloted them. Not wanting to be left behind, Beachey knocked on the door of the Wright Brothers, imploring them to train him to fly in their behalf. Orville and Wilbur, however, wanted Beachey to pay them $500 for the opportunity — a sum that was out of the question for the penurious Beachey. Hat in hand, he accepted a less desirable position as a mechanic with Glenn Curtiss’ outfit. Eventually, he cajoled Curtiss into letting him practice flying a biplane during off hours.

By his own admission, Beachey was inept at first. Though one might not think of flying as a skill best learned by trial and error, according to Marrero’s book, Beachey spent considerable time repairing gears damaged by hard landings. Months passed before his aerial proficiency improved.

When Curtiss’ top pilot, Charlie Hamilton, was seriously injured during a December 1910 flying exposition in Los Angeles, Curtiss reluctantly tapped Beachey to finish out the meet. Blustery conditions made flying difficult for the nervous Beachey, though he relaxed after discovering the plane’s natural stability tended to even out the rough ride.

That sense of stability didn’t last long. After climbing to 3,000 feet, the plane’s engine stalled out and an eerie silence ensued. In the early days of flight, this scenario rarely ended well for the pilot. Beachey began plummeting toward the Earth, his craft spiraling out of control. The natural, though often futile, reaction for pilots faced with this predicament was to try to wrestle the plane up and out of the spin, causing the plane to spin even faster. Beachey sensed he could avoid a crash by nosing the plane completely into the dive. This counterintuitive move provided sufficient power for Beachey to regain control. He landed with the exultant roars of the crowd ringing in his ears.

Afterward, Curtiss said to him, “Linc, that was as fine a demonstration of flying as I’ve ever seen. Thank God, you’re alive.”

The flight was something of an epiphany for the young pilot, too. “Mr. Curtiss,” he said, “in the silence I could finally feel the whole machine for the first time. I think I know how to fly now.”

On the heels of this sensational debut, Beachey entered a January 1911 air exhibition held in his hometown of San Francisco. The show featured competitions in racing, take-offs, altitude, landing and showmanship. Lincoln blew away all challengers, winning several contests including “shortest take-off,” for which he earned $1,000.

As he was emerging as an aviation rock star, more than 17 million people would witness his flying feats in over 100 cities during 1911. His derring-do, newfound fame and money brought him attention from admiring females. Though Beachey had married North Carolinian May (Minnie) Wyatt during his dirigible days, those vows didn’t seem to deter the flyer from accepting the company of other young women during his wanderings around the country. To persuade the objects of his affection to join him in a fling, he would offer them diamond engagement rings, which he purchased by the dozen. He made a practice of keeping one at the ready in his vest pocket and is said to have had fiancées awaiting nuptials in cities across the U.S.

The dalliances, however, did not distract Beachey from formulating new and more dangerous aerial maneuvers. Now widely referred to as the “Birdman,” or “The Man who Owns the Sky,” he practiced longer and steeper dives, producing breathtaking close calls. Beachey claimed he was no daredevil and that his extraordinary stunts simply underscored the fact that the normal flying of an airplane was a safe activity. His feats, however, had the opposite effect on public perception, since an alarming number of less-skilled aviators perished in attempts to emulate his maneuvers. The frequency of horrific accidents led to ghoulish betting activity at airshows regarding the likelihood of a fatality.

Notwithstanding this gladiators’ arena-like gruesomeness, aerial shows were beginning to emerge as a bona-fide American sport. The article in The Outlook trumpeting Beachey’s arrival said as much. “Several pupils and a big gallery of ‘fans’ come with Mr. Beachey to enjoy the sport, (for that is what it is rapidly developing into).” The paper offered the view that “as an entertainment novelty, the school promises to be the biggest feature in the history of the Village.” The Outlook even predicted that golf would, for the moment, be “back grounded by interest in the ‘Bird Man.’”

In 1911, no airfields existed in the Sandhills, so the Curtiss representatives needed to locate a Pinehurst property with dimensions sufficient to accommodate the taking off and landing of the biplane. They selected a large field on high ground west of the Aberdeen, Carolina and Western railroad track in the vicinity of what is now Linden Road.

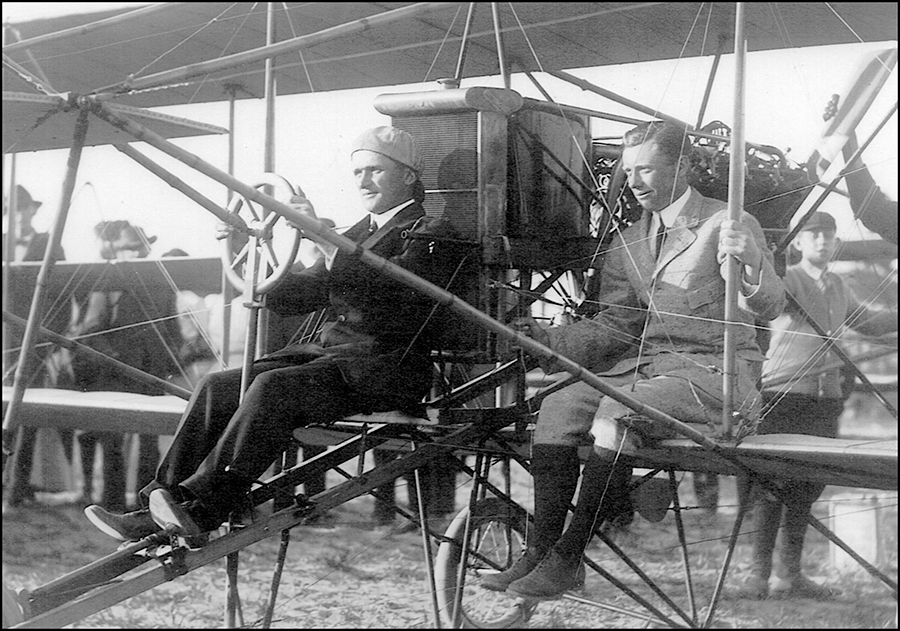

Beachey and wife Minnie arrived in Pinehurst on March 18 and bunked at the Berkshire Hotel. The following morning, he made his way to the makeshift airfield and personally took charge of assembling the biplane. By noon, he had the engine whirring with (as The Outlook described it) a “resonant roar.” In short order, Beachey was soaring over Pinehurst, accompanied by the biplane’s mechanic.

Next, he treated R.B. Middleton to his maiden airplane ride. Middleton, a race car driver from New York, aspired to be an ace aviator under Beachey’s tutelage. Another noteworthy passenger was Commander (later vice-admiral) Shichigoro Saito of the Royal Japanese Navy. According to The Outlook, Saito “left bubbling over with enthusiasm, convinced of (an airplane’s) practicability for Army and Navy uses.”

Minnie also hitched a flight with her husband, though her presence in Pinehurst may not have entirely inhibited Lincoln’s roving eye. The Outlook reported that Miss E. Marie Sinclair, “an accomplished and daring sportswoman,” was “favored with a long and high flight.”

Another first-time passenger was acclaimed amateur golfer Chick Evans, in town for the United North and South Amateur, which he won. If Evans wasn’t the best American golfer in the era immediately prior to the emergence of Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones, he was close. He defeated all the top pros in the 1910 Western Open (then considered a major championship), and later won both the U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur in 1916.

Evans would confess to pre-flight jitters. “Before my ascent,” wrote the golfer, “I imagined the most acute feeling on leaving my old friend the Earth, would be fear; the shuddering, awesome, sort of fear which assails a boy when passing a cemetery on a dark night.” But Evans’ anxiety was allayed once above the pinewoods, where “a profound sensation of security came over me, and while the rush of air was tremendous and the revolutions of the high-power motor deafening, I felt as safe as if sitting upon a sheltered balcony.”

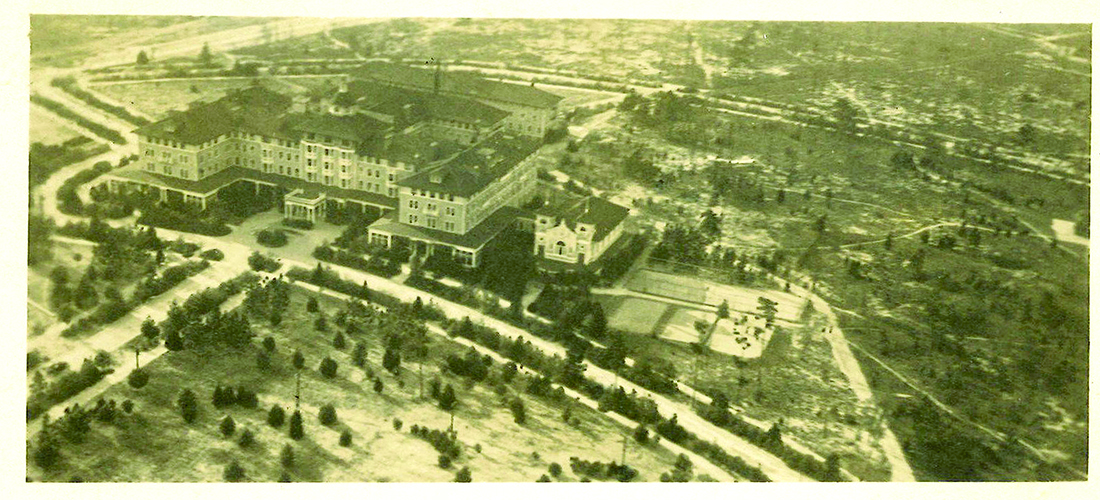

Evans’ observations of flight painted a vivid picture. “The world we were leaving became very small — a strange little boy world. The great Carolina Hotel was the Noah’s Ark of my childhood.” To Evans, the people gathered on the ground resembled “a regiment of toy soldiers.” He marveled at the sight of “the golf links, a beautiful stretch of soft green, with strange square inserts to mark the putting greens, and the winding roads, silver ribbons; with the surrounding landscape stretching on and on, like the ocean, to infinity.”

When the Pinehurst resort’s lead photographer, Edmund L. Merrow, got wind of the fact that the Curtiss team was offering rides to intrepid passengers, he inquired whether the team would permit a photographer to snap pictures of Pinehurst from the air. The taking of photographs from an airplane was a nearly unheard of activity. No passenger, let alone one schlepping a camera, boarded a plane until 1908. The first such picture-taking occurred in 1909 when a passenger on a plane flown in Italy by Wilbur Wright filmed a three-minute motion picture. It appears that the first aerial photos from a plane in American skies occurred above San Diego in January 1911, just two months before the Curtiss biplane’s flights over Pinehurst.

Merrow convinced the Curtiss team to allow someone to tag along as Beachey’s passenger and take aerial pictures, but the 51-year-old elected not to undertake the project himself, delegating it to his 29-year-old assistant, Ellsworth C. Eddy. The two men had been associated since around 1900, when Merrow hired the young Eddy to assist him at his photography shop in Bethlehem, New Hampshire. During the winter months, Merrow would migrate south to Pinehurst, where he photographed dances, sporting activities and various goings-on at the resort. In 1907, he persuaded Eddy to join him in the Sandhills. During the ensuing four years, the two men were a photographic team, rotating between New Hampshire and Pinehurst, depending on the season.

For Eddy, camera work in Pinehurst had been an enjoyable, though not especially profitable, gig. It allowed him an opportunity to hobnob with celebrities like bandleader John Philip Sousa and sharpshooter Annie Oakley, and now Beachey, Saito and Evans. Flying was not something Eddy was eager to experience, but his assignment required it. As he approached the biplane on March 25, 1911, Eddy presumably wondered whether his $17 per week paycheck was worth it. Would he ever see his wife and children again?

Eddy was greeted at the Curtiss tent on March 25 by the confident Beachey, garbed in coat, vest, white shirt and tie with hat turned backward. Eddy’s diary reveals his trepidation. “I was scared at first when the pilot said before he would take me up, I would have to sign a release absolving him of any liability.”

Despite misgivings, Eddy signed the exculpatory document, and after being outfitted “in a leather jacket, goggles and hat tied on,” he found himself aloft with Beachey over Pinehurst. Buffeted by the wind, his vision impaired by goggles, and struggling to maintain his balance sans seat belt while hoisting the camera, the picture-taking was cumbersome if not downright harrowing. But Eddy managed to snap six pictures of the town and airfield below.

The images clearly depict early Pinehurst, then 16 years in existence, and still in the nascent stages of development. No longer a denuded pine barrens, hundreds of newly planted trees and other ornamental plantings created a boulevard affect along Carolina Vista, Magnolia and Ritter roads. In 1911, the latter road, unlike today, passed directly in front of the Carolina Hotel. The “Music Room,” shown at the right of the hotel, would later be razed and replaced by another structure that currently houses the hotel’s spa. While a substantial number of homes are visible, housing density is low. The tented Curtiss airfield is depicted with onlooking spectators.

His nerve-racking camerawork made young Eddy something of a trailblazer. He may have just missed being the first aerial photographer shooting from an airplane in the United States, but Steve Massengill’s book, Around Southern Pines, A Sandhills Album, confirms Ellsworth’s photos were the first such taken in North Carolina.

From their studio on the corner of Chinquapin and Magnolia roads, Merrow and Eddy immediately converted the unique images into postcards, and by early April they were on the market. According to local historian Larry Koster, “Pinehurst postcards were a cheap, easy way for the many tourists to convey both the beauty and attractions of this area to the folks back home.” They also provided wonderful advertising for the resort.

Koster, who authored the 2009 publication The Photographers of Moore County and Their Postcards, has been searching for and collecting vintage Pinehurst postcards for 25 years. He eventually acquired examples of all six postcards depicting the aerial images taken by Eddy and, in recognition of their historical significance, has donated them to the Tufts Archives.

On Thursday, April 7, 1911, Beachey, according to The Outlook, “took the big bird apart, packed it in its snug cage and left for Fayetteville, the first point of many which lie before him.” Waxing eloquently, the article noted that residents would miss the plane’s “weird notes at dawn, twilight or high noon, its presence in the sky, the grotesque, fleeting shadow.”

The writer compared the sight of Beachey’s jaw-dropping flights to “the grandeur of Niagara — the spectrum in the spray and the roar of the waters.” The reference proved a precursor to Beachey’s incredible exhibition at Niagara Falls less than three months later, on June 26, 1911. For the stupendous sum of $4,000, he dove his Curtiss Pusher straight for the center of Horseshoe Falls, his aircraft suddenly vanishing in the mist. Many spectators swooned at what they perceived was the pilot’s certain demise. With spray stinging the Birdman’s face, his plane suddenly shot out “like a cannonball” from the bottom of the mist, after plunging to within inches of the raging river. Having been offered an additional bonus of $1,000 for flying beneath the arch of Honeymoon Bridge, Beachey promptly tacked on that daunting stunt. One newspaper declared him “the eighth wonder of the world, and his dive into the Falls, the greatest aerial feat of all time.”

In August, Beachey performed more amazing exploits at a Chicago aerial competition. He shattered the world record for altitude, attaining 11,642 feet, but it was his crowd-pleasing stunts that would be remembered best. Eyeing a locomotive headed into the city, he dropped down to brush his wheels atop the train, then passed within spitting distance on both sides of the passenger cars while waving to those inside. Then, Beachey hopped his plane from one car to the next.

In a subsequent flight, dressed as a woman for dramatic effect, he frightened the spectators with a seemingly out of control dive directly at the grandstand. Beachey pulled the plane up just 8 feet from mayhem. He turned and headed toward the central city, where he ducked under power lines, bounced off tops of cars and buildings, then landed to a 10-minute standing ovation after pulling off his wig revealing his true identity. In a rather somber note, two pilots attempting similar dives crashed and died at the meet.

Over the next three years, Beachey’s aerial acrobatics would further cement his fame. Even Orville Wright acknowledged his aerial mastery. “Beachey is more magnificent than I had imagined,” proclaimed Wright. “I have watched him closely with my glasses and have never seen him make an error or falter. An aeroplane in the hands of Lincoln Beachey is poetry . . . He is the most wonderful flyer of all.” Thomas Edison paid similar tribute.

His numerous affairs ultimately undermined Beachey’s marriage. Minnie divorced him in 1913. In the court proceeding, she claimed her husband had conducted illicit affairs in 32 cities. One headline read, “Aviator’s Conquest Not of Air Alone.” He also received increasing press criticism because so many pilots perished in attempts to duplicate his various stunts. A San Diego Union editorial, noting his “wild performances,” opined that “there is serious doubt as to whether Beachey should be allowed to continue.” The barrage took its toll on the flier, who announced on May 13, 1913, “You could not make me enter an aeroplane at the point of a revolver. I am done.” In his statement, Beachey castigated the attendees at his exhibitions, saying they “paid to see me die.”

His retirement, however, was short-lived. Four months later, he was flying in exhibitions again. Instead of throttling back his theatrics, the Birdman presented an array of new tricks in his comeback: flying both upside down and backward, inside and through a San Francisco building. He raced his plane around a track against the country’s top race car driver, Barney Oldfield. At times during a race, Beachey would cause the front wheel of his plane to graze Oldfield’s head.

Then, in November 1913, Beachey debuted a maneuver which would become his signature stunt: the loop-the-loop, in which he would dive, pull back on the controls at 1,000 feet, then climb until the nose of the airplane would fall back beyond the vertical. Then he would repeat the stunt — again and again. He conceded he was pushing the limits. “I do not intend to let the margin of safety and disaster be any wider than I can help. Beachey never cheats the crowds, that is, excepting those who come to see me die.”

His acrobatics drew the attention of America’s top military brass, who were starting to realize that the maneuvers Beachey had mastered could have application in warfare. In September 1914, the secretaries of the Army and Navy invited him to Washington, D.C., for a demonstration. Beachey was intent on making an impactful splash. At one point, he aimed his biplane toward the Oval Office of the White House, where an aghast President Woodrow Wilson saw him coming. The Birdman pulled up and away at the last instant.

Similar acrobatics were directed at the Capitol Building. Congress was then in session, but promptly adjourned so that the members could view Beachey’s theatrics. If any legislator present harbored doubts regarding the usefulness of airplanes in wartime, Beachey’s performance erased them. When subsequently huddled with assembled Congressmen, he remarked, “If I had had a bomb, you would be dead. You were defenseless. It is time to put a force in the air.”

In March 1915, Beachey came home to San Francisco to perform at the Panama Pacific International Exhibition. As he strolled around the fairgrounds arm-in-arm with his new 23-year-old fiancée Merced Wallace, his star was at its zenith. In the four years since his Pinehurst visit, he had become an aviation legend and an A-list celebrity. To honor their hometown hero, the organizers had proclaimed March 14 “Beachey Day.”

There had also been significant changes in the life of Ellsworth Eddy since his flight with the Birdman. He had left Merrow’s employ in the fall of 1911 because his salary was insufficient to support a family. To make ends meet, he worked at the Carolina Hotel for a year, renting out horses to guests. In the spring of 1913, he opened his own photography studio on Pennsylvania Avenue in Southern Pines and became the town’s go-to photographer until he and his wife retired to Florida in 1946. He passed away in 1973, at age 91.

Lincoln Beachey was not destined to approach the photographer’s lifespan. His demise was especially ironic. It came after he said he would give the 50,000 Beachey Day spectators, “a show they’ll never forget.” While flying his new monoplane, Beachey launched into one of his patented dives. The right wing of the plane suddenly failed, breaking under the pressure. Then the left wing followed suit. As the enormous San Francisco crowd watched in horror, he crashed into the bay at 210 miles per hour. Though surviving the initial impact, he was unable to get free from his restraints and drowned. Lincoln Beachey was just 28.

Tributes to the “Man who Owned the Sky” came from all over the country. There were plans for a permanent memorial in San Francisco, and money was contributed for that purpose though the funds were subsequently repurposed toward America’s efforts in World War I.

As new aviation heroes like Eddie Rickenbacker and Charles Lindbergh took the national stage, memories of Beachey and his incredible early achievements faded into obscurity. He was elected to the Aviation Hall of Fame in 1966 and the International Acrobatics Hall of Fame in 1990. And a small band of aviation devotees still honor the flyer every March 14 — Beachey Day — by dropping pink roses into San Francisco Bay.

In Pinehurst, a town that venerates its storied history, the whirr of his biplane’s engine is a distant memory preserved only in a picture postcard captured by a reluctant cameraman. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at william.case@thompsonhine.com.