Metamorphosis of a village showplace

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

Hundred-year-old houses like Red Gables harbor mysteries, secrets. Who (or what) was Ailsa, the name on the gate shingle — a girl or the islet off Scotland? What is known about the people who autographed boards — one dated 1918 — uncovered during renovation, now framed in the kitchen? And why — in an age when Pinehurst homes had a crawl space, at best — does this house own a brick-walled basement sturdy enough to withstand a tornado?

“I kept driving by . . . I always wanted to live in the house,” says Holly Davis.

Now, she does. After 18 months of respectful renovation and new construction, the house within sight of the Carolina Hotel is once again a showplace, a comfortable family home and gallery for Southern folk art.

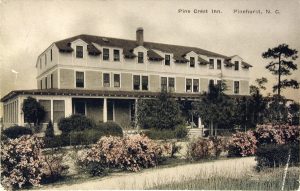

By the early 20th century word had spread through the Northeast that Pinehurst was a desirable winter destination for high society — and so much closer than Palm Beach. Some snow birds stayed at hotels or rented one of the founder’s, James Walker Tufts, cottages, while the deepest pockets built their own. In 1909 Mrs. Emma Sinclair of Boston commissioned architect W.W. Dinsmore, also of Boston, to build what the Kennedys might call a compound: two structures collectively named Red Gables after the clay-tiled roofs, so she could winter alongside her daughters. In 1918 the property was sold to Henry B. Swoope, a Pennsylvania coal baron.

Red Gables, along with its sister cottage and log cabin, changed hands several times, endured multiple updates, but stood empty and sad when a friend told Holly that, finally, the property was for sale.

“I was glad the house needed work,” Holly recalls. “That scared off people. I could see the potential.”

Holly grew up in Illinois, moved to Durham; her husband, Carty Davis, comes from New Orleans. They lived in Atlanta before deciding a smaller city would be better for the children. The area offered schools, culture, interesting people. In 2002 they built a residence in Forest Creek. Holly, who studied graphic design at N.C. State, enjoys building and renovating. “I can (visualize) the space when I see plans, which is helpful.” Eventually, like many transplants, they gravitated to the village. “I much prefer a historic house with so much more character,” Holly says.

This she vowed to preserve by keeping the footprint virtually intact and cherishing details, such as crystal teardrop sconces and chandeliers, oversized windows, a glass-front built-in bookcase. Instead of a spa tub, she refinished a claw-foot, original to the house. Aesthetically reluctant to convert to gas, four fireplaces trimmed in exquisite moldings still burn wood.

Vinyl trim was replaced and a fresh layer of stucco applied to exterior walls which, with the red tile roof, completed the Mission style that caused a ripple in the early 1900s. Alas, the tile roof is gone, but fat Tuscan columns — another uncommon architectural detail — remain on the porch.

Some interior space was rearranged, but not the twin entrances placed on opposite sides of the living room with its coffered ceiling — once dark wood, now painted white. Holly deemed the dining room unnecessary. Instead, she used it for a family room-den and placed a small, elegant round dining table with curved upholstered chairs at one end of the living room. Most mealtimes the family gathers around an 8 1/2-foot kitchen table made to order using lumber salvaged from Liggett & Myers Tobacco Co. warehouses.

Main floor space was also adjusted for a master suite, leaving the three upstairs bedrooms for guests.

Mrs. Emma Sinclair, the Swoopes and their nine children would gasp at the kitchen, which had been redone,’70s fashion, when the Davises purchased the house. Holly wanted everything ripped out, including the ceiling and room above it, making way for a vaulted space clad in painted wideboards, with recessed lighting. This established a scale suiting tall cabinets, a marble island and countertops, and a range hood befitting a castle, all in soothing gray and white. No tabletop appliances or gadgets break the expanse.

“I’m not a clutterer,” Holly says.

But she is a collector. “I love Southern primitive folk art,” which she encountered near the Davises’ beach retreat on Fripp Island, South Carolina. “The raw materials, the emotions — they paint about life,” often life filled with poverty and pain in the post-Reconstruction South. Her favorites include Sam Doyle, a black artist from St. Helena Island, South Carolina, who painted on scrap metal in the African-influenced Gullah tradition. Figures are flat, frontal; coloring is primary, bold. Also represented is Clementine Hunter from Louisiana’s Natchitoches Parish. Hunter, a domestic servant at Melrose Plantation who could neither read nor write, painted on any objects she could find, as well as canvas. She died in 1988, at 101, leaving a thousand visual memories of her gritty existence.

Holly successfully juxtaposed a scene by Alabama farmhand Jimmy Lee Suddeth, who used a mud-based paint tinted with berries, against a marble-topped antique chest from Carty’s Louisiana homestead. Other pieces were brought back from a family trip to Africa.

But, in truth, no period or style defines the result. Holly’s aversion to clutter extends throughout the house, which is furnished with a spare hand, allowing each piece an impact. She trolls junk stores for dressers, headboards and other pieces, paints and “distresses” them herself to resemble well-worn heirlooms. Neutrals prevail except for bursts of color — bright navy on a bedroom carpet and spread, an even brighter orange chair illuminating another bedroom, one small olive green wall in the monochromatic kitchen, sunflowers and orchids in the living room — pure panache.

Across the stone terrace stands a massive new garage with an upstairs office-apartment and balcony, designed and stucco-clad to blend with the house. When landscaping the triple lot Holly was able to retain decades-old plantings, which shield them from traffic. “But we like hearing music (from events on the green) and the bagpiper,” who serenades the hotel every evening. When the Davis children are home they walk to the Roast Office for coffee; Carty Davis and yellow Lab Charlotte are regulars in the village.

Houses, like crops, fashions and seasons, move in cycles — at least the lucky ones. Red Gables, aka Ailsa House, long a wallflower, blooms a debutante once again, this time with all-new systems and wine shelves in her cellar fortress.

Credit Holly’s patience: “I just hope what we’ve done to this home will make it last another hundred years.” PS