Little Big Man

How mighty mite Alfred Moore became our county’s namesake

By Bill Case

By 1781, the Revolutionary War had raged in America for five years. North Carolina had mostly escaped armed conflict since the spring of 1776 when early Patriot successes caused Loyalist militia to disperse and British soldiers to vacate the Cape Fear area. Wilmington was a hotbed of independence, controlled by Patriots devoted to their cause. But in the first month of 1781, British general Lord Charles Cornwallis, seeking to restore hegemony in North Carolina, ordered a contingent of 300 redcoats commanded by Maj. James H. Craig to sail from Charleston to Wilmington and occupy the city.

Immediately after stepping onshore at the city’s wharf on January 28, 1781, the ruthless Craig ordered Wilmington citizens to declare their allegiance to King George III or face the plundering of their possessions and a possible death sentence. As historian James Sprunt put it, Craig mercilessly employed “fire and sword” in his dealings with leading Patriots, burning their homes and jailing the most prominent while imploring Loyalist sympathizers to join militia units and assist in his scorched earth campaign to destroy “every Whig (Patriot) plantation.” Many Cape Fear Tories who supported English rule but had been laying low since 1776 became emboldened to take up arms against their fellow citizens.

This turn of events alarmed 25-year-old Alfred Moore, who lived with wife Susannah at “Buchoi,” their rice plantation 7 miles from Wilmington. He reckoned himself a target for Major Craig’s wrath since several Moore family members, including Alfred himself, had played key roles in the Patriot victories of 1776. Now, after a five-year hiatus, they again confronted the prospect of fighting forces antagonistic to independence.

Indeed, Alfred’s family had been a dominating presence in the Carolinas almost since colonization began. In the late 1600s, his great-grandfather of Irish ancestry, James Moore, acquired by dint of marriage vast amounts of land in the Carolinas. From 1700 to 1703, James served in Charles Town (today’s Charleston) as royal governor of Carolina — the colony would not be split into two until 1712. One of James’ six sons, James Jr., a noted Indian fighter, would later serve briefly as provisional governor of South Carolina. With further land acquisitions by James Sr.’s sons, the combined Moore families amassed ownership of 83,000 acres by 1731. One of those sons, Maurice, chose to settle not far from Wilmington, founding the now defunct town of Brunswick on the Cape Fear River. Maurice’s son, Maurice Jr. (Alfred’s father), would become a well-known attorney, and one of three royal judges in North Carolina.

In 1766, Maurice Jr. authored an inflammatory pamphlet denouncing the hated Stamp Act, imposed by the British Parliament on the colonies. His provocative writing so angered the royal governor that Maurice Jr. was briefly stripped of his judgeship. Despite his disapproval of English policy, Maurice Jr. tended to vacillate on the issue of whether the colonies should make a total break from the mother country. His son Alfred held no such reservations. After the opening shots of the Revolutionary War were fired on the outskirts of Boston, at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Alfred, recently admitted to the bar, postponed his legal career and joined the newly formed Continental Army.

Boston was where Alfred had been sent for schooling after his mother died when he was 9 years old. While there, he rubbed elbows with soldiers from the British garrison, impressing the commander sufficiently that he saw fit to offer the by then 13-year-old an ensign’s commission. Moore was now eager to fight the foe that had attempted to recruit him as a boy.

Moore was appointed a captain in the North Carolina First Regiment, led by his uncle Colonel James Moore — a canny leader the nephew held in high esteem. The regiment became a true family affair when Alfred’s brother Maurice III and brother-in-law Francis Nash signed up, too. The regiment’s most memorable encounter came the following February against 1,600 Tory militia, mainly Scottish Highlander immigrants. The militia was on the march from Cross Creek (subsequently Fayetteville) to Wilmington, intending to link up with Sir Henry Clinton’s redcoat army en route from the north. The Tories never reached Wilmington. Led by Colonel Moore, the Tories were routed at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge. Those not killed or wounded scattered into the woods. Captain Alfred Moore and his regiment distinguished themselves by cutting off the Tories’ retreat and rounding them up. The Patriots’ smashing victory meant that North Carolina would be effectively rid of active Loyalist militia for the time being.

The two most important men in Alfred’s life, his father, Maurice Jr., and uncle James (who had been promoted to brigadier general by General George Washington), died in the same house on the same day — January 15, 1777 — victims of a plague. Compounding the family tragedies were the deaths in battle of Maurice III and Nash. The resulting turbulence in family affairs necessitated Alfred’s attention at home, so he resigned his commission and stayed behind in North Carolina after Washington ordered the First Regiment to New Jersey in March 1777. Moore remained involved in the independence cause as the leader of his local militia. With hostilities ebbing for the moment in the Carolinas, he was able to devote time to his legal career and resume his role as the master of Buchoi.

So, when Major Craig stormed into Wilmington four years later, issuing an ultimatum that those of Patriotic leanings must pledge unswerving loyalty to King George — or else — Alfred Moore faced a dilemma. If he swore, he would betray his cause. If he refused he faced the loss of all material possessions, a life on the run and perhaps his own death. Some Patriot supporters submitted to Craig’s demands, but Moore would not bend. Instead, he and his band of militiamen became guerrillas, making themselves a “thorn in the side” of the British. The exasperated Craig softened his stance a bit, indicating that if Moore would simply agree to take no further part in the war, he and his property would be left undisturbed, but Alfred rejected this entreaty. In retaliation, Craig dispatched a raiding party to Buchoi. The plantation’s buildings and crops were burned, Moore’s livestock removed, his family’s personal possessions plundered, and his slaves freed.

Meanwhile, British Gen. Lord Cornwallis had been active in the interior of the Carolinas fighting engagements against Gen. Nathaniel Greene’s army, including the Battle of Guilford Courthouse near Greensboro, on March 15, 1781. Though the British were deemed the victors of that encounter, Cornwallis’ provisions and troops were greatly depleted. When he and his soldiers marched southeast to Wilmington for resupplies, Moore’s militiamen made life miserable for them. Disappointed with the lack of his campaign’s progress in the Carolinas, Cornwallis moved north into Virginia, where his troops were trapped at Yorktown, ultimately surrendering to Washington on October 19, 1781. The despised Craig would hang on in Wilmington until November 18, when he, his remaining troops and any Loyalists who wanted to accompany them evacuated the city. The war was over.

Moore’s defiance of the British left him “ruined in fortune and estate,” wrote one observer, “his family almost destitute of food and clothing.” On the plus side, he still possessed his law license, and the admiration of his fellow citizens. That would prove to be enough to begin a career that would carry him all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

In January 1782, while traveling in the company of Judge John Williams and fellow attorney William Davie, on a stopover in Hillsborough, the three men learned that seven Loyalist militiamen were languishing in custody at the local jail awaiting trial for treason and other grave misdeeds during the war. Annoyed that the trials of the seven defendants had yet to occur, authorities in Hillsborough implored Judge Williams to hold an immediate special session to try the captives. Williams was agreeable, but Attorney General James Iredell, who normally would bear responsibility for prosecuting, was elsewhere. Williams persuaded the 26-year-old Moore to stand in for Iredell. Davie agreed to undertake the Loyalists’ defense. According to Robert Mason’s biography of Alfred Moore, Namesake, Davie pithily summarized the trials this way: “Moore prosecuted all, I defended all and Williams convicted all.”

While previously recognized as a patriot and war hero, Alfred’s successes in Hillsborough brought recognition as a highly capable lawyer. The combination of his military accomplishments and legal victories provided an ideal stepping-stone for a political career and Moore took advantage. After his bravura legal triumphs, he became a Federalist Party state senator in North Carolina’s General Assembly. In 1783, when Iredell resigned as attorney general, Moore expressed interest in the post, and the General Assembly unhesitatingly confirmed him.

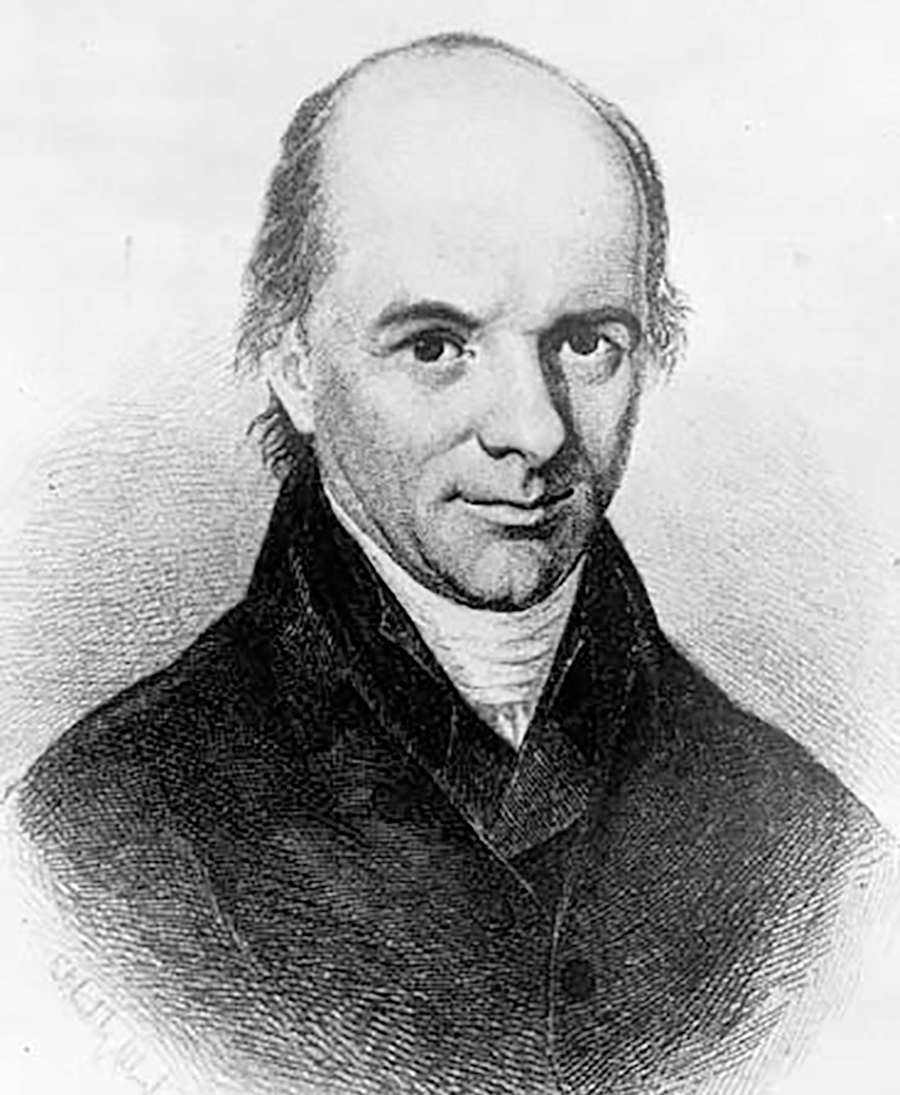

During his eight-year tenure in that position, Moore’s friend, Davie, often served as opposing counsel. Their legal tussles provided entertaining theater for the onlookers who regularly packed courtrooms to observe the talented lawyers engage in forceful forensic battles. Their oral argument styles differed — Davie adopted a lofty, florid, flowing style, while Moore spoke with “plainness and precision.” Moore was described in an 1899 speech by Junius Davis as having “a dark singularly penetrating eye, a clear sonorous voice . . . a keen sense of humor, a brilliant wit, a biting tongue [and] a masterful logic [that] made him an adversary at the bar to be feared.” Moore and Davie along with James Iredell (who would in 1790 join the United States Supreme Court) constituted a brilliant legal triumvirate, unquestionably the giants of the early North Carolina bar.

It should be noted that the term “giant” cannot be applied in any literal sense to Alfred Moore. He was a man of the slightest stature. Accounts vary as to whether he stood 4-feet-5-inches or 5-feet-4-inches. Perhaps a dyslexic historian mistakenly transposed the 5 and 4 somewhere along the way. But the late William Rehnquist, former chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and a fastidious researcher, says in his book, The Supreme Court, that Moore “apparently looked much like a child, being only four and a half feet tall, and weighing between eighty and ninety pounds.”

Though he endured suffering inflicted by Tories during the war, Moore declined to pursue a path of vengeance against them in post-war prosecutions. In an article written for the North Carolina History Project, Willis P. Whichard says that Moore “was realistic about the prospect of jury nullification in these largely political prosecutions; he accordingly often pursued lesser charges and by doing so achieved a higher conviction rate than Iredell’s.”

In the aftermath of the war, many Tories fled North Carolina. Their land was seized by the government and sold to bidders at “confiscation sales.” To aid these purchasers, the General Assembly passed a law in 1785 denying courts the authority to hear cases involving challenges to titles granted by the sales. Nonetheless, Mrs. Elizabeth Bayard, a British subject and the daughter of a deceased Tory whose property had been confiscated and sold over her objection, filed suit claiming that the seizure and sale were unlawful and that, by virtue of inheritance from her father, she should be acknowledged the rightful owner of the property. Mrs. Bayard further asserted that the aforementioned 1785 law was in conflict with her rights under the North Carolina Constitution, which guaranteed to her the right of trial by jury in matters pertaining to the recovery of property. Essentially, Mrs. Bayard was requesting that the court declare the 1785 legislation unconstitutional — something that had never happened before in America. Alfred Moore represented North Carolina. His friendly rivals William Davie and James Iredell appeared on behalf of Mrs. Bayard in the case styled Bayard v. Singleton. Ultimately, the judges hearing the case agreed with Mrs. Bayard that she was entitled to a jury trial, declaring the 1785 legislation “unconstitutional and void.” Though she won this battle, Mrs. Bayard lost the war. At the trial, the jury found against her claim because, as a British subject and enemy alien, Mrs. Bayard possessed no rights to hold property in the state. Thus, Moore’s advocacy upheld the legality of the confiscation sales. Of more lasting import was the fact that the Bayard case represented the first time an American court declared a legislative act unconstitutional due to its conflict with a written constitution.

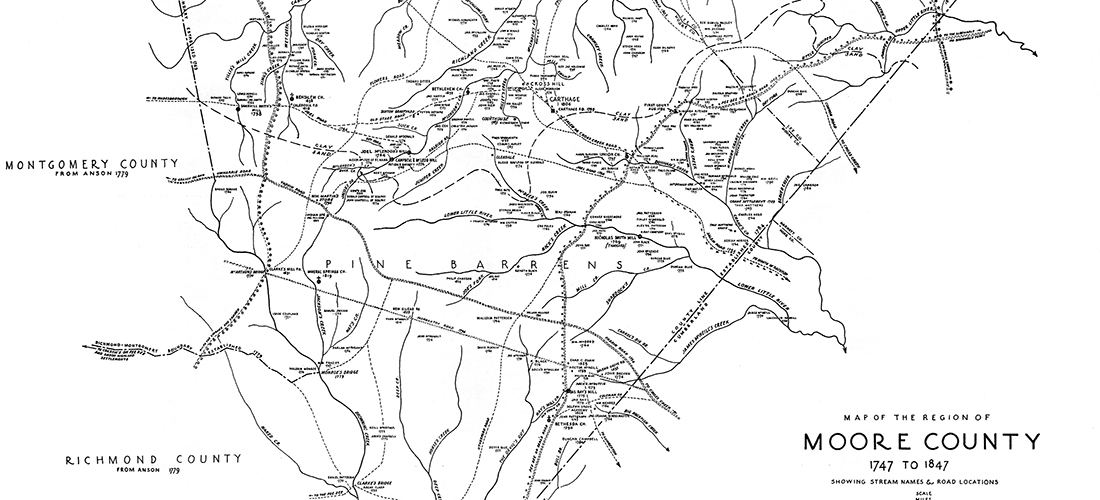

It was during Moore’s time as attorney general that the General Assembly named a county in his honor. Realizing in April 1784 that the western part of Cumberland County was too remote from that county’s political hub — present day Fayetteville — the General Assembly carved out that portion for a separate governmental entity, naming it Moore County just prior to Alfred’s 29th birthday. It is unknown whether he ever actually set foot there. Other counties were likewise named for his legal cohorts, Davie and Iredell.

Both Moore and Davie urged the General Assembly to give birth to a public university in North Carolina. After an unsuccessful legislative attempt to do so in 1784, the two lawyers continued the drumbeat for founding one. Finally, in 1789, the University of North Carolina was chartered with Moore and Davie named to its first board of trustees. According to Mason’s namesake, Moore “helped to select the university’s site at New Hope Chapel, seat of an Anglican parish, which became Chapel Hill. Also, he was on the committee that chose a seal, and one of the three trustees who drafted a regulation disallowing the sale of intoxicants within two miles of the campus.” In addition, Moore was a benefactor to the school, gifting it $200 along with two globes to be employed as teaching aids.

The middle 1780s were a time of passionate dispute over how much power the states should delegate to the new federal government. Federalists like Moore fervently believed his state should ratify a new constitution that would greatly enhance the weak powers provided to the United States government by the Articles of Confederation. But many North Carolinians, mindful of their former colony’s oppression by King George III and Parliament, feared the concept of a remote centralized government controlling their lives. Following an initial rejection, North Carolina approved a revised constitution after it was amended to include a Bill of Rights, and Moore’s unstinting support of the ratification effort contributed to its ultimate success.

Miffed that the General Assembly had created a new office of solicitor general that essentially duplicated the powers and duties of the attorney general, Moore resigned from the latter post in January 1791. By this time, Moore’s Buchoi rice plantation was thriving once more. A man of his time, he acquired more slaves. He also purchased 1,200 acres in Hillsborough, residing in a second home there called “Moorefields,” which stands today. Alfred and his family relished summer interludes at Moorefields, invigorated by the area’s cooler air, a particularly welcome relief to wife Susannah, an asthma sufferer.

Moore couldn’t resist governmental service for long. By 1792, he was seated again in the General Assembly. Later, he would accept President (and fellow Federalist) John Adams’ nomination to serve as one of the United States commissioners entrusted “to conclude a treaty with the Cherokee Nation of Indians.” But Moore yearned for a more prestigious position and set his sights on becoming a United States senator. In the early days of statehood, North Carolina’s General Assembly selected the senators. Alfred twice stood for election by the Assembly. In 1794, he was edged by a one-vote margin favoring Jeffersonian candidate Timothy Bloodworth. His 1798 run for the Senate sputtered after his friendly rival, Davie, withdrew his support of Moore’s candidacy as part of a strategy to secure his own election as governor.

Moore’s wounds were salved by his appointment to a state court judgeship. The appointment made possible his following in the judicial footsteps of his father, Maurice Jr. There is a split of opinion regarding Alfred’s performance during his short-lived tenure as a state court judge. Historian Samuel A.C. Ashe faulted him for habitually disregarding precedents, but North Carolina Supreme Court Chief Justice John Louis Taylor praised Moore’s service, saying that “the acuteness of his intellect and his experience in business enabled him to decide very complicated cases with great promptitude and general satisfaction.”

When the 48-year-old Iredell, who was among President Washington’s first appointees to the United States Supreme Court, died suddenly in Edenton on October 20, 1799, it was anticipated that the resulting vacancy would be filled by a lawyer from the Carolinas, given that Supreme Court justices of the era doubled as circuit riders, presiding over federal criminal trials and lower court appeals emanating from their particular geographic area. Iredell’s circuit responsibilities had required backbreaking horseback rides to distant towns in the Carolinas and Georgia as well as the nation’s capital — exhausting rigors that contributed to his early demise.

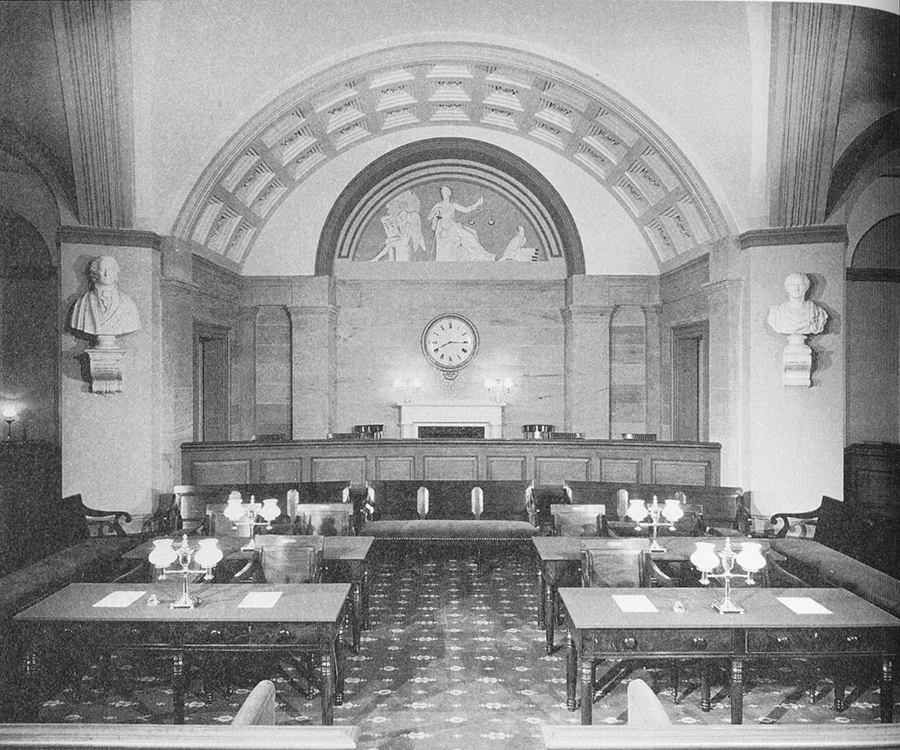

Given his steadfast support of the Federalist Party and his negotiation of a treaty with the Cherokees, Moore stood in good graces with John Adams. Still, it seemed improbable that the president would consider him to fill the high court vacancy. Moore had been a judge less than two years, and there were many able Federalist jurists in the Carolinas who possessed experience far exceeding his own. According to Whichard, Moore and Davie were the only candidates seriously considered by Adams. The president, while undoubtedly appreciating both men’s loyalty to the Federalist Party and status as war heroes, had recently appointed Davie as special envoy to France. Moore emerged as the choice to join what was then a six-member Supreme Court and became just the 12th justice to be confirmed by the Senate on April 21, 1800. To Moore’s relief, the Federalists passed legislation that eliminated the justices’ circuit-riding duties shortly after he joined the court.

After Moore’s ascension to the high court, John Marshall became its chief justice. Marshall, still considered the greatest and most influential justice in the long history of the court, dominated it, overshadowing Moore and the other justices. He assigned to himself most of the court’s written opinions, which were relatively few because, according to Rehnquist’s book, “the principal source of its appeals — the lower federal courts — had not been in existence long enough to decide any cases that could be appealed to the Supreme Court.”

All of this explains why Moore authored only a single written opinion during his time on the court. In that case, Bas v. Tingy, a privately owned American ship, the “Eliza,” had been captured by the French (who were then engaging in hostile activities toward America), and then subsequently recaptured by an armed American ship. The amount to be paid by the owner to the salvager increased exponentially if the recapture was of a ship that had been seized by an “enemy.” Because no formal state of war existed between the United States and France, the owner maintained that he was not required to pay the higher fee to the Eliza’s salvager. Justice Moore disagreed with this contention, finding that the owner needed to pay the higher salvage fee because a state of “limited, partial war” existed between the United States and France.

Perhaps the most important case in Supreme Court history was decided during Moore’s tenure. In Marbury v. Madison, Justice Marshall, speaking for the court, held that the Supreme Court possessed authority to void an Act of Congress because of unconstitutionality. This momentous decision marked the second time any American court had claimed authority to void legislation for that reason. The first was the Bayard decision in which Moore had played a starring litigation role. Ironically, Moore was the lone justice not to participate in Marbury v. Madison. It is unknown why.

It appears Moore did not particularly enjoy his time on the United States Supreme Court, serving less than four years. Events occurring in 1802 had much to do with his dissatisfaction. First, the United States Treasurer failed to pay his modest salary in a timely manner. Second, the Jeffersonians who had come to power in both Congress and the presidency enacted legislation reviving the grueling circuit riding by the justices. Moore was appalled. “Can it be believed,” he would write a friend, “I can ride 2,840 miles a year with any regularity to attend to business on the seat of justice — the number of cases to be determined is by no means so disturbing as getting to them?” Moore told his friend that for the short term he would endure the hardships, not wanting an “uncharitable conclusion” to be drawn from an abrupt departure. But after what he considered a suitable wait, he announced his departure and left the court on January 26, 1804. He and his friend Iredell remain the only North Carolinians to have served as justices on the Supreme Court of the United States.

The circuit riding had already taken its toll on Moore’s frail body. He retired to the Bladen County plantation of his daughter, Anne, and her husband, Hugh Waddell, where Moore’s health continued to decline. He died at age 55 in his daughter’s home on October 15, 1810. His public service legacy was carried on by son Alfred, who was a member of the General Assembly and served as mayor of Wilmington.

It is noteworthy that Moore directly followed Iredell into the two most important positions of his illustrious life: as North Carolina’s attorney general and as a Supreme Court justice. It was said about them in one testimonial that “[a]t the bar they ever disdained the small arts of the pettifogger, and upon the bench blindfolded, they ever held the scales of justice with an even hand, treating with equal impartiality the rich and the poor, the guilty and the innocent.” Though slight of build, for a man who may never have walked in the county named for him, Moore left a large footprint. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.