Art Nouveau and a 19th century Warhol

By Jim Moriarty

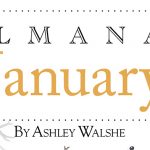

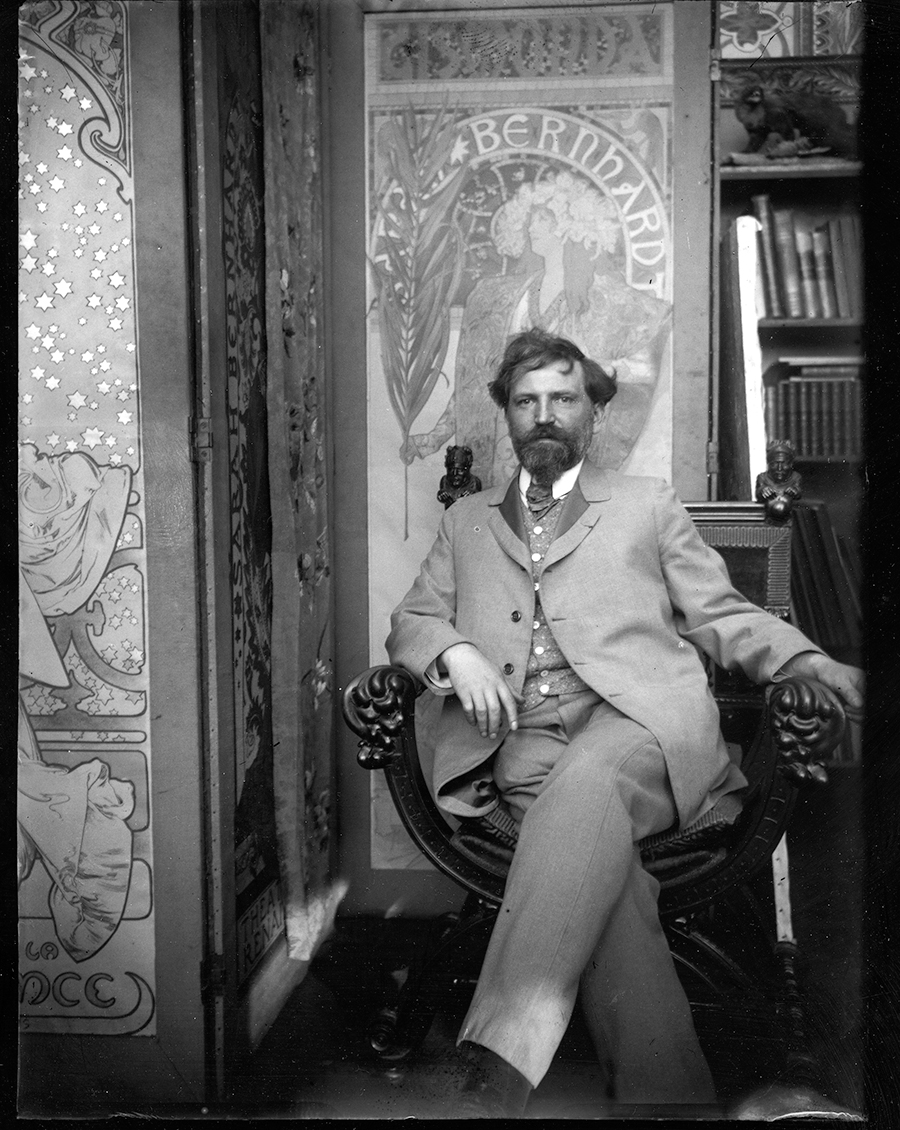

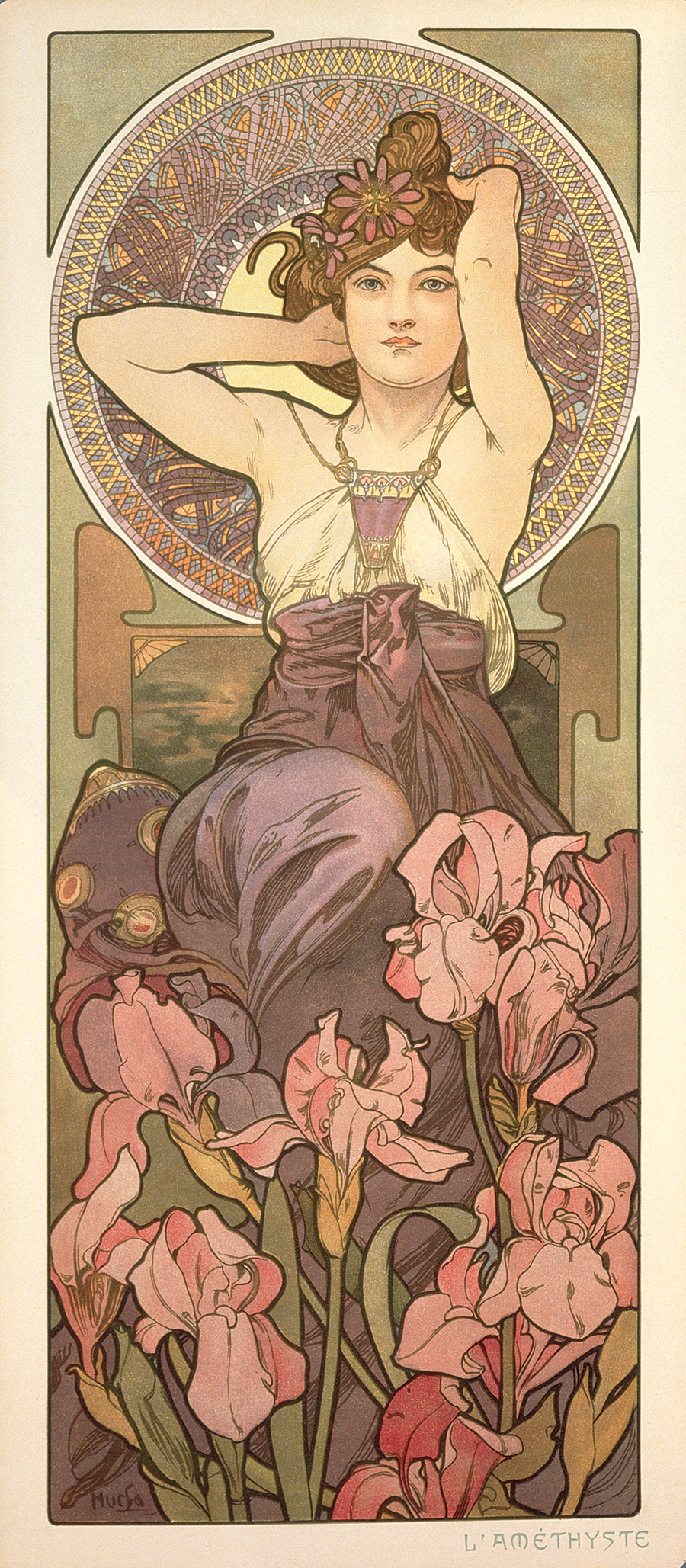

Though no single artist invented the late 19th century Art Nouveau movement in the way Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque defined cubism, Alphonse Mucha’s name appears at the very top of the rolling credits. The grand sweep of his life and career, everything from his ground-breaking lithographic posters and photography to his decorative commercial work on products like champagne and chocolate, his friendships with Paul Gauguin and Auguste Rodin, his links to mysticism, and his staunch Slavic patriotism, are all on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art through Jan. 23.

Think of Mucha as the Andy Warhol of his era. He was to lithographic printing what Warhol became to screen printing. “Warhol appropriates mass culture in a way that’s different from Mucha, but he is associated with celebrity (Marilyn Monroe) in a very distinct way. Mucha gets his start working with Sarah Bernhardt in Paris, who is a superstar actress at the time. He makes a name for himself with images of a famous woman in a very similar way to Warhol,” says Michele Frederick, the associate curator of European Art at the N.C. Museum of Art.

Mucha and Warhol were artistic rock stars of their day, financially successful juggernauts, turning commercial imagery to suit their own artistic aesthetic. “The idea of breaking down barriers between fine and applied arts and using commercial language in what becomes fine art is very similar,” says Frederick. It was at the very heart of Art Nouveau — the rejection of a rigid, classical definition of what subjects and forms could define what was art and what wasn’t.

“Art Nouveau in Paris is essentially invented by Mucha in the 1890s,” says Frederick. It was called Le Style Mucha.

Mucha’s commercial art, breathtaking in its execution, was innovative in ways that remain distinctly modern. One of the posters in the exhibit is for Cycles Perfecta, a bicycle company. “He doesn’t really show much of the bicycle,” says Frederick. “You can’t tell if it has two wheels or two pedals or a seat. What he’s showing you is what it feels like to use this product. When you think of a company, like Apple, some of its most iconic advertisements show you what it feels like to use an iPod, not how it works. That’s something that’s super modern.”

Born in 1860 in the small town of Ivančice in what is now the Czech Republic, Mucha’s training was traditional in every regard. He studied at the Munich Akademie der Bildenden Künste (the academy of fine arts) and then the Académie Julian in Paris. His breakthrough work was a poster commissioned by Bernhardt for the play Gismonda at the Theatre de la Renaissance. The play opened with great success in October of 1894, and its run was being extended beyond the Christmas holidays. Bernhardt wanted a new poster to be hung on Jan. 1, 1895, advertising both herself and the play. The poster depicts Bernhardt in a richly embroidered costume with a mosaic-tiled wall and Orthodox cross in the background.

“For Mucha,” writes Tomoko Sato in his book Alphonse Mucha, “Byzantine civilization was the spiritual home of Slavic culture . . . Mucha’s use of the Byzantine motif in Gismonda was partly influenced by the mediaeval Greek setting of the play; nevertheless, from around 1896 onward, Slavic motifs became a regular feature of Mucha’s posters.”

In 1894 Mucha met and became friendly with the Swedish writer August Strindberg, who at the time was consumed with concepts of mystical forces and the occult. “Mucha was profoundly influenced by Strindberg’s notion of ‘mysterious forces’ that guided a man’s life,” writes Sato. “This was later to contribute to Mucha’s own idea of ‘unseen powers,’ which is manifested in his work as the recurring motif of a mysterious figure appearing behind the subject.” Mucha’s spiritual journey led him to Freemasonry, which he practiced for the remainder of his life.

“So much of Mucha’s art 100-plus years later looks very French to us,” says Frederick. “Preserving the idea of his Czechness is very important. He’s not just a commercial artist, he’s a political artist as well, especially later in his career.”

After repeated trips to the United States, wealthy Chicago businessman Charles Richard Crane (son of the plumbing parts baron Richard T. Crane) agreed to finance Mucha’s grand opus, The Slav Epic, a patriotic project that would consume the last decades of his life. He began working on the first of what would become 20 monumental paintings — the largest is 19 1/2 feet by 26 feet — in 1911, when his homeland was still ruled by the Hapsburg monarchy, consolidated then as the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1928, marking the 10th anniversary of the creation of Czechoslovakia following the end of World War I, Crane and Mucha together bequeathed the paintings to the city of Prague. The N.C. museum’s exhibit features large digital projections of the paintings as well as close-up views of some of their details.

“I am convinced that the development of every nation can only be successful if it grows organically and uninterruptedly from its own roots, and the knowledge of its past is indispensable for the preservation of that continuity,” Mucha said at the ceremony donating the works.

The peace and independence of Mucha’s Slavic homeland was short-lived. In 1933 Adolf Hitler became the chancellor of Germany. In March of 1939, German troops marched into Prague, and Hitler declared the establishment of the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Mucha was arrested, then released, by the Gestapo. He died four months later. PS

Jim Moriarty is the Editor of PineStraw and can be reached at

jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.