How Southern Pines artist Doris Swett created the most enduring image of the longleaf pine, leaving a legacy of helping others in her native Sandhills

By Bill Fields

Two weeks after Pearl Harbor was attacked, on a front page dotted with war-related stories — the death of a Navy sailor from Vass, donations for the Red Cross, requests for civilian defense volunteers — The Pilot’s Dec. 19, 1941 edition looked different for another reason too.

Gone was a banner of a captain and county map inside a ship’s wheel that had been used as the newspaper’s banner for a dozen years. The nautical theme was replaced with a nameplate that better reflected the publication’s location and also added some cheer at a grim time.

“In due keeping with a festive Christmas season,” the newspaper wrote, “The Pilot this week dons a new banner heading and nameplate, especially designed for the paper by a local artist who has won fame for her etchings of long-leafed pines of the Carolinas and Florida. Miss Ruth Doris Swett, Southern Pines native and daughter of the late Dr. William P. Swett, one of the county’s pioneer builders, executed the original drawing of the pine needles, the compass and the map of Moore County which will adorn the top of The Pilot’s front page from now on.”

Swett’s creation, debuted between pleas to buy defense stamps and bonds on a paper that sold for a nickel, was a stylish upgrade from the cliché clip-art look of its predecessor. For generations of residents and visitors, the pine bough-adorned nameplate — whose map included the hamlets of Samarcand, Jugtown and Niagra — symbolized the Sandhills like Midland Road, Stoneybrook or yielding to the left on Broad Street.

That Swett could connote such an effective sense of place when The Pilot commissioned her to revamp its look 75 years ago was no surprise. She was part of one of Southern Pines’ foremost pioneering families. Weary of Northern winters, Dr. Swett and his wife, Susan, moved to Southern Pines in 1892, only five years after the town was chartered. In addition to his medical practice, Swett, a Vermont native, grew peaches, organized the Southern Pines Country Club and was a leader in Emmanuel Episcopal Church. Ruth Doris, known to family and friends by her middle name, was born in Southern Pines on Jan. 11, 1901, the youngest of five children. Two of her siblings died young: Mabel Lois was only a year old when she passed away in 1898; William Louis passed away at 16 in 1907.

After Susan Swett’s death in 1915, Dr. Swett married Grace Moseley, in 1918. “Aunt Doris was very young when her mother died, and her father was very concerned about her being by herself,” says Doris’ great-niece, Mary Ruth Prentice. Sadly, it was a short union. While Doris was attending St. Mary’s School in Raleigh, Dr. Swett died suddenly of heart failure at age 67 on April 13, 1921, as he was rousing guests from their rooms at the Southland Hotel when a fire ravaged downtown Southern Pines, destroying a block of wooden buildings.

The Medical Society of North Carolina had a meeting later that month in Pinehurst, where another Sandhills physician, Dr. W.C. Mudgett, praised Swett. “He was sincere, ethical, honorable, despising that which suggested commercialism,” Mudgett said, “forgetting himself and considering only the greatest good for his patients . . . He died in the very manner in which he had expressed the hope that his final summons might come: still active, still in service.”

Doris and her stepmother grew very close, the duo once going on a two-year grand tour of the world before the Great Depression devastated the family finances. “They were well-off, and then they pretty much got wiped out,” says Prentice, who inherited some of the poetry books her great aunt purchased on her global adventure. “Her stepmother, ‘Molee,’ we called her, was a lovely lady. She became blind, and Aunt Doris really took care of her in her last years.”

Despite the family traumas, Doris Swett developed into a serious and talented artist. She studied at Chouinard Art Institute in California and the Art Students League of New York, and under painter and lithographer Margery Ryerson and South Carolinian Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, a leader in the Charleston Renaissance. William Charles McNulty, a printmaker and editorial cartoonist, was also an influence.

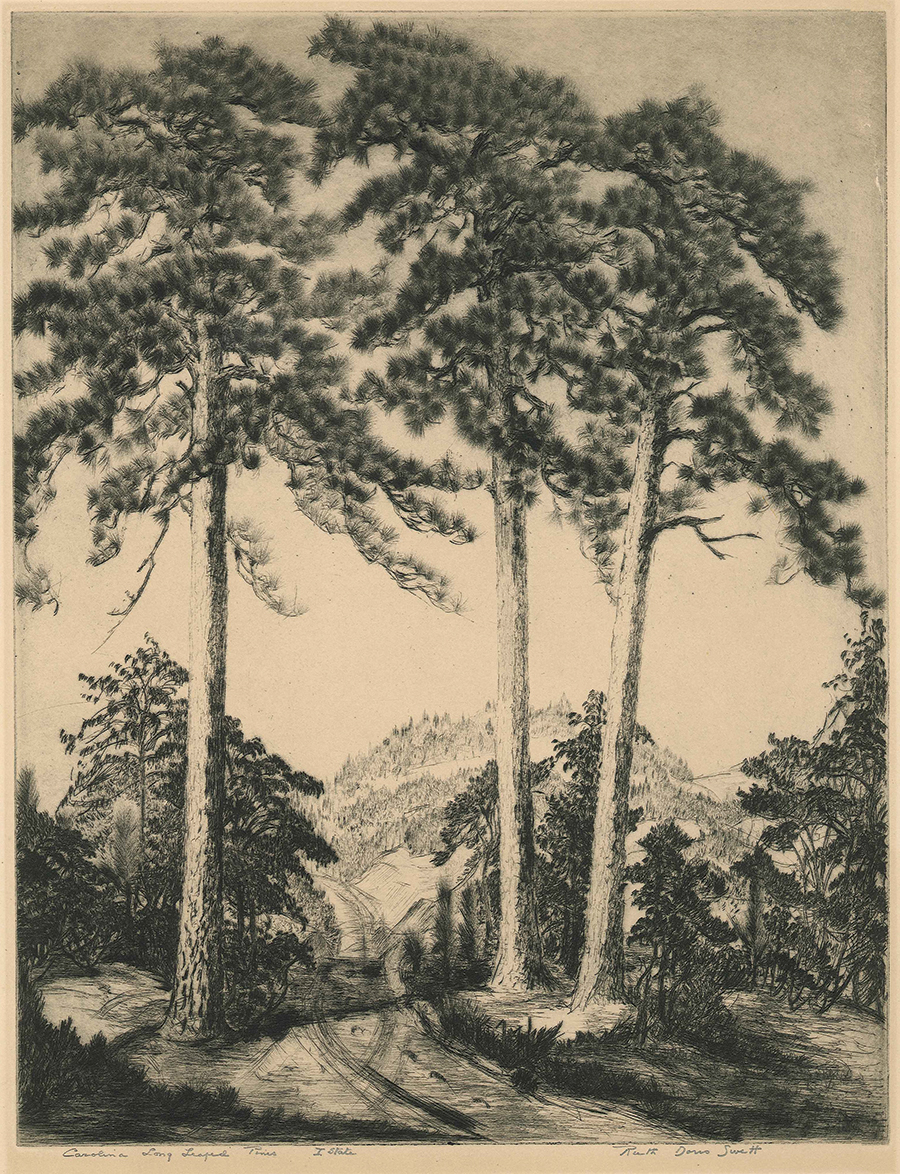

Swett worked in various media but specialized in etching, The Pilot reported in a 1935 story, “after inspiring associations with George Elbert Burr in Arizona.” Burr (1859-1939) was a well-regarded American artist known for his Western landscapes who did illustrations for Harper’s, Scribner’s Magazine and Frank Leslie’s Weekly. Swett came to know Burr after he settled in the 1920s in Arizona. The desert and mountain vistas of his adopted home were frequent subjects for his drypoint, a printmaking method in which an artist scratches an image on a metal plate — often copper — with a diamond-tipped needle, or stylus.

Like Burr, Swett focused her drypoint on familiar scenes, the tall trees of her native North Carolina as well as central Florida, where she sometimes wintered and for a time taught etching at Rollins College in Winter Park, Fla. Swett’s art was frequently mentioned in The Pilot’s pages during the mid- to late-1930s and early 1940s. The Sandhills Book Shop sold prints of her work. “Etchings including her distinctive Pines,” read a 1938 advertisement for the store in The Pilot. “We have them in many sizes, suitable for framing, or for gift cards.”

During this period, Swett’s work was exhibited in Charlotte, New York and Boston. One of her etchings of western North Carolina served as the frontispiece for a 1936 book on Beech Mountain folk songs and ballads. That spring, her drypoint prints were part of a show at the Smithsonian National Gallery in Washington, D.C., where Swett drew high praise from critic Leila Mechlin, former longtime editor of The American Magazine of Art.

“Without restricting herself to any one kind of tree, Miss Swett has undoubtedly specialized in transcribing the long-needle pine of the South and has done it beautifully,” Mechlin wrote in the Washington Evening Star. “There is something very graceful about these typically Southern trees with their tall straight trunks and magnificently tassled heads. But they are not easy to etch, for they combine both strength and softness. Their long leaves are like needles, but against the sky they appear as soft as velvet to the touch. It is just this combination of strength and lightness that this young etcher gets in her plates — especially in prints showing single branches and plumed twigs.”

Eighty years after Mechlin’s favorable critique, Denise Baker, a Whispering Pines artist who works in drypoint and is a retired Sandhills Community College art instructor, agrees.

“Her drypoints are exceptional,” Baker says. “I feel her style was very indigenous. It was very much like a sense of place, where she was at the time. It takes physical strength to do a drypoint because you have to get the needle down in the metal but still have that fluidness of line, which she was so very good at.

“The woman had to have incredible strength to do the beautiful work in that medium,” Baker continues. “If you’re a painter, you get to watch it in progress. But when you’re working on a metal plate, until you put the ink on and it goes on the press, you don’t really know if all those hours you’ve spent are coming to fruition.”

Swett put aside her art to concentrate on caregiving and church in the post-war years, her younger relatives recalling a generous spirit.

“She was extremely kind,” says Prentice, who grew up in Red Springs. “Of the three great aunts who would come visiting, she always made you feel important — your dolls, your stories were important. She was a very elegant and soft-spoken lady, very loving. I never saw anger in her.”

Swett’s great-nephew David Barney remembers her as a quiet person, smart, with a keen sense of humor. “She had been a fine tennis player at one time,” he says, “and you could tell she had been an athlete. I didn’t spend a lot of time around her, but I admired her and wish I had known her better.”

For many years Swett lived with her stepmother and an aunt, Alice Southworth, in Briarwood, a rambling Spanish Mission-influenced house on Weymouth Road in Southern Pines that had been built as a seasonal residence for Southworth. Filled with antiques, the home had a central skylight in a sitting room but lots of gloomy corners.

“My younger brother and I loved roaming around that house,” says Prentice, “thinking we could find treasure or hidden places.”

Swett died at age 65 in Moore Memorial Hospital, on April 12, 1966, of a heart attack, two days after being admitted. She was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery alongside her parents and other family members, including her stepmother, who had passed away three years earlier. “Extremely shy and retiring,” The Pilot concluded in its obituary of Swett, “she literally devoted herself to helping others in a mission of kindness and quiet piety.” Swett’s sister, Katherine, the last surviving child, died at 80 in 1968.

Following Doris Swett’s death, her Pilot nameplate remained in use for another 33 years. In a typographic makeover of the newspaper, The Pilot replaced the Swett design starting with its Sept. 2, 1999 edition. An updated map inside a compass, sans a pine drawing, was utilized. “We’ve introduced a bolder, simpler nameplate,” wrote then-editor Steve Bouser, “taking care to preserve the flavor of the old.”

Three of Swett’s drypoints — “Florida Pine,” “The Lone Palm” and “Long Leaf Pine” — are in the Fine Prints collection of The Library of Congress. Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill has Swett’s “A Winter Park Pine” and “Via Tuscany Pines” in its collection. Several Swett prints have sold at auction in recent years for between $100 and $500. At a reunion about a decade ago, relatives chose as dozens of their great-aunt’s signed prints were divided up among family members.

“One of my cousins brought lots of pieces and we all were able to get something,” says Barney. “I’m really glad that happened, because it’s extraordinary stuff — the delicacy and form of my aunt’s work is really wonderful.”

And it appeals because of more than technique.

Says Prentice: “I was born in Pinehurst. I look at those longleaf pines, and it takes me right back home.” PS