Leonard Tufts’ love affair with adventure motoring

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

By 1911, Pinehurst, only 16 years in existence, had become one of the pre-eminent resort destinations in America. Northerners arriving by rail flocked to the Sandhills to experience the golf, equestrian activities, hunting and fine dining, offered by the resort. Bostonian and soda fountain magnate James W. Tufts founded the town and resort in 1895. But after his death in 1902, it was his son, Leonard, who masterminded changes in business practices that bolstered Pinehurst’s financial viability during the first decade of the 20th century.

James Tufts had never turned a profit in the seven years he served at the resort’s helm. Leonard flipped the bottom line when he started selling lots and existing cottages in Pinehurst to prominent Northerners. These “cottage colony” residents needed products and services of all kinds and, as the sole proprietor of a company town, the savvy Tufts was in a position to provide these various commodities at a fair profit to himself.

Leonard was never one to rest on his laurels, and was always on the lookout for potential storm clouds that, left unaddressed, could impact the resort’s future success. He viewed the emergence of the automobile as presenting just such a challenge. Though Tufts’ guests from the North were still content to visit the town by rail (the first guest to motor from New England to Pinehurst did so in 1909), he foresaw a not-too-distant time when they would be traveling to vacation destinations in their own autos. If Southern roads (and those around Pinehurst) remained in their poor condition, these patrons would likely choose to spend their holidays in more auto-friendly locations.

That very thing occurred at a hotel near Leonard Tufts’ summer home in Meredith, New Hampshire. An excellent roadway had been constructed straight from New York City to the doorstep of the Waukegan House — a distance of 400 miles. Auto enthusiasts from the city began making the drive to the Waukegan in droves, transforming a struggling hostelry into a blockbuster.

“Automobiles are going across the road continuously,” Leonard observed, “oftentimes one hundred or more arrive in a day.” This was precisely the kind of road accessibility Tufts craved for Pinehurst.

Many who shared Leonard’s concerns about roads chose to address the issue by berating state and local officials to fix things. That was not Leonard Tufts’ style. Instead, he immersed himself in local, regional and national road improvement activities and associations. In June 1909, he helped organize a conference of good road proponents in Columbia, South Carolina, attended by over 100 representatives from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The purpose of the gathering was to discuss the establishment of a continuous highway from Washington, D.C., to Atlanta that would pass through Richmond, Raleigh and Columbia — all capitals of their respective states. The road was to be dubbed the “Capital Highway.” The representatives on hand in Columbia selected Leonard to head up the project.

Tufts explored ways of promoting the new highway. One possibility involved an automobile reliability contest tour between New York and Atlanta sponsored by the New York Herald and Atlanta Journal newspapers. The papers announced they would be awarding a $1,000 prize to the county found to have the best roadway on the tour. Leonard concluded that competition for this prize would provide a powerful incentive for counties along the Capital Highway to improve their respective sections of the road. He urged the two newspapers to hold the southern portion of the tour on the Capital Highway instead of a more westerly path through the mountains proposed by a rival group. Leonard pointed out that the mostly sandy surfaces of the Capital Highway were superior to those of the red clay mountain roads, which often became impassable when wet. Unfortunately, the newspapers ignored his plea, opting to conduct the contest over the western route.

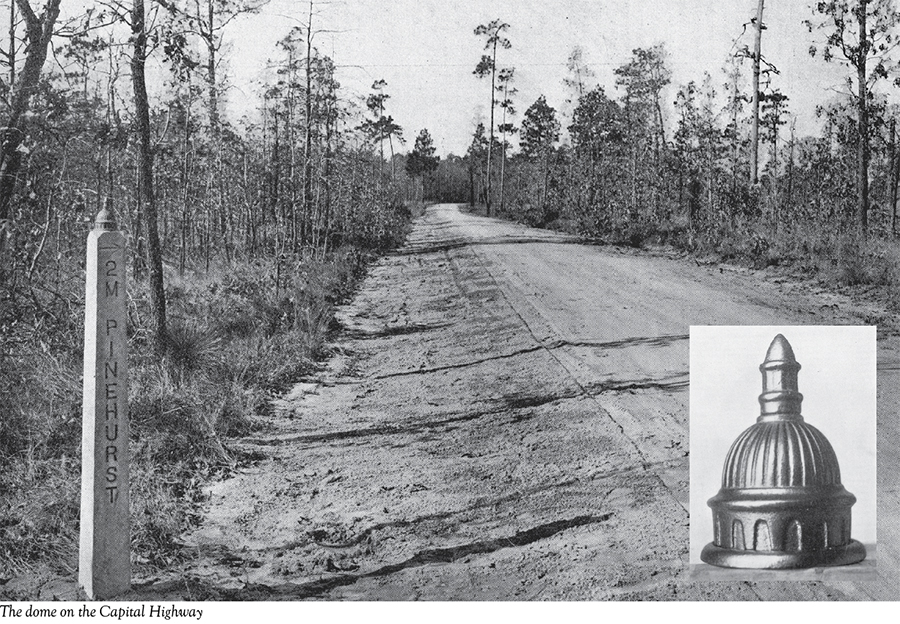

This setback did not deter Tufts’ relentless championing of the Capital Highway. He beseeched local officials along the route to provide funding for improvements, and Leonard subsidized many of them himself. Though the highway’s path through North Carolina largely followed what is now Route 1, Tufts made sure that the road veered through the middle of Pinehurst. To promote the highway’s branding and identification with state capitals, he caused Capitol dome likenesses to be placed atop highway mile markers. Guidebooks were made available to motorists that described every zig and zag of the highway in an easy-to-follow manner. Other materials provided info on the various resorts near the highway where weary travelers could bivouac.

Leonard also paid attention to the accessibility of roads near Pinehurst. Surmising that resort guests would eventually be taking day trips in their flivvers touring Moore County’s countryside, he laid out and improved a number of roads in the vicinity. He also involved himself in an ambitious mapping project of the county for the benefit of both guests and future development.

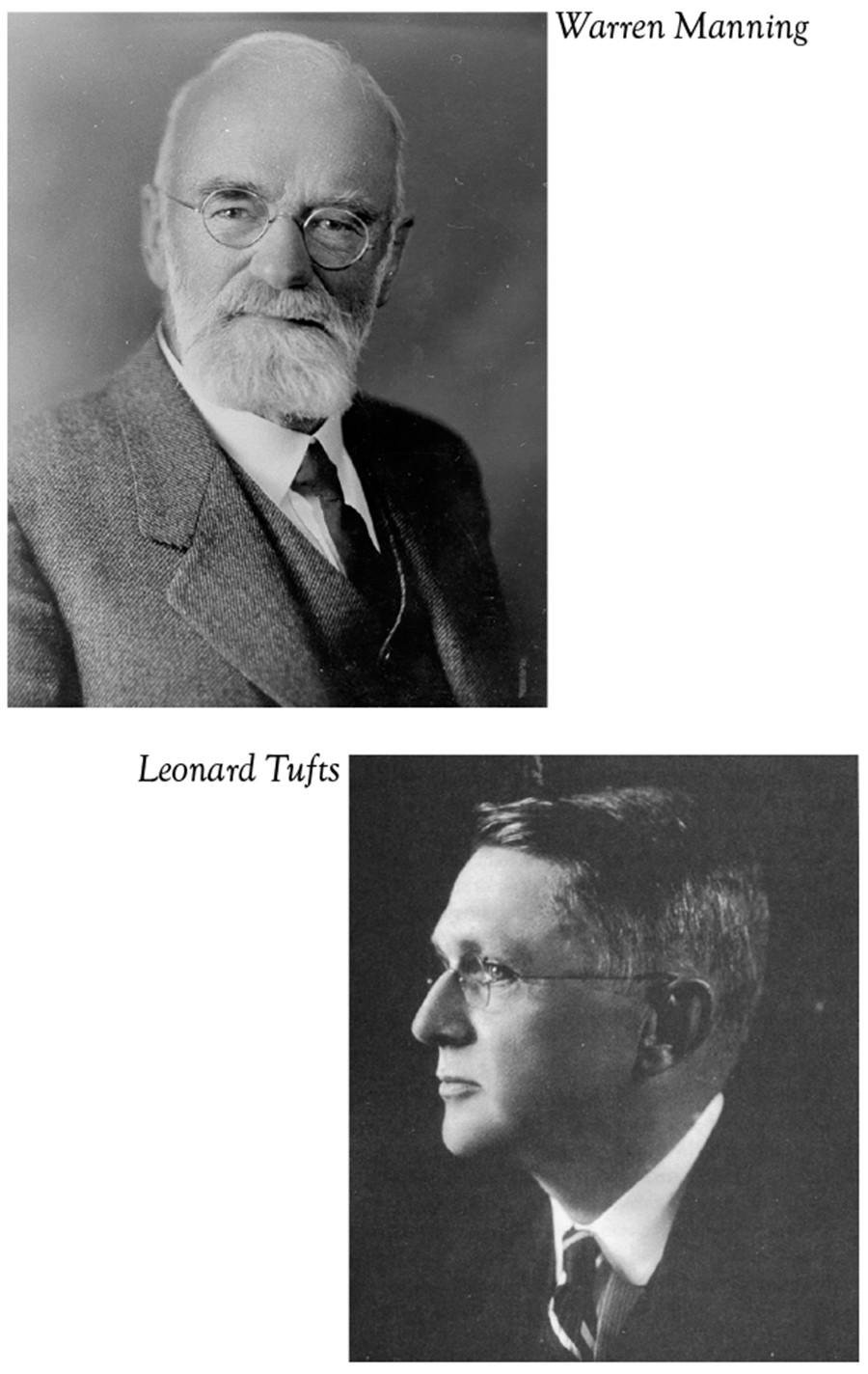

Accompanying him on these forays into the hinterlands was 49-year-old Warren H. Manning, the man whose creative tree and plant selections had transformed Pinehurst from a denuded pine barrens into a veritable “Garden of Eden.” While employed with the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted (the designer of New York’s Central Park), Manning arranged the plantings for the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the Biltmore House in Asheville. He also assisted Olmsted in laying out Pinehurst’s unique serpentine roads. Manning ultimately left Olmsted’s firm to start his own landscape architecture business, taking the Pinehurst account with him. Soon, he established his own national reputation for designing naturalistic “wild gardens.”

Though his services were in increasingly high demand, Manning always found time to work on Pinehurst projects. He and Tufts had formed such a close bond that the architect frequently lodged at Leonard’s Mystic Cottage home when on assignment in the Sandhills.

The two friends made something of an odd couple, motoring through Moore County’s hills. The scholarly, 40-year-old Leonard, usually toting a book under his arm, calmly and deliberately eyed every feature when they disembarked to inspect the surrounding terrain. By contrast, the peripatetic, square-bearded Manning often appeared oblivious to anything except the task at hand. He speed-walked from point to point, recording notes and measurements, and generally leaving his younger cohort in the dust. According to Tufts, the architect was “the ‘walkingest’ man” he had ever encountered.

Tufts’ work on Moore County roads did not distract him from overseeing his pet project — the Capital Highway. Though it was now open to motorists, Leonard was concerned that parts of the highway were still not up to snuff. He also suspected local counties and other governmental entities along the route were not pulling their weight in maintaining their respective portions of the road. When the Pinehurst resort closed for the season in May 1911, Tufts decided to make his annual migration to Meredith, New Hampshire, by automobile so he could examine firsthand the northerly half of the highway running from Pinehurst to Richmond.

Three men joined Leonard on the 800-mile expedition: his frequent sidekick Manning, Dr. Myron Marr, and Charley Cotton. The 31-year-old Marr, a native of Dorchester, Massachusetts, had become quite a fixture in Pinehurst Country Club circles. Whether golfing with the Tin Whistles organization, competing in equestrian events, playing doubles tennis with his wife, or shooting trap, the doctor was very much in the club’s mix. He also enjoyed a pleasant gig as the “resident physician for Pinehurst,” with morning visiting hours (or by appointment) at his conveniently located office inside the Carolina Hotel. Like most denizens of Pinehurst’s Cottage Colony, the coming of May signaled the time for Dr. Marr to be heading to New England, so he was presumably pleased to be hitching a ride with Tufts.

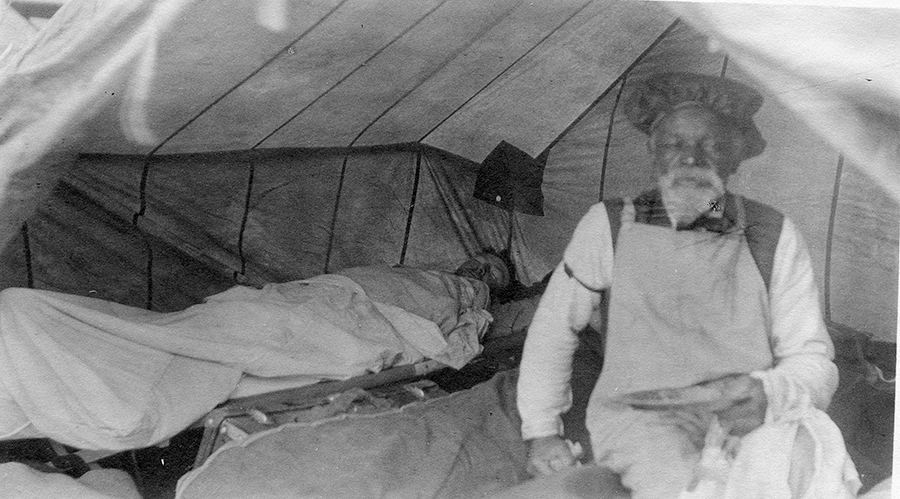

According to later reminiscences of Leonard’s son, Richard, Charley Cotton, the fourth member of the group, went along “to assist in making camp and with the preparation of meals.” Originally born into slavery, the 60ish, white-bearded Cotton had long worked for Pinehurst and the Tufts family. “Uncle Charley’s” whimsical observations and homespun horse sense charmed his fellow travelers, contributing much more to the journey than his labor.

Manning kept a journal, housed at the Tufts Archives, of their road trip and snapped a number of photographs as well. His first entry says, “I arrived at Pinehurst, 9 a.m., May 6, 1911, attended to plans and telegram, lunched with Mr. Tufts and Dr. Marr under Minnie’s ministrations, got into khaki and flannel shirt, helped pack auto (Leonard’s 4-cylinder Reo with steering wheel on the right side), then we started at 3 p.m.” After a brief stop in Southern Pines for additional supplies, the Reo headed north in “perfect” weather — at an excellent clip of 22 mph.

As might be expected, many of Manning’s journal entries pertained to plants, trees and gardens he observed along the way. As the quartet steamed up the Capital Highway, the landscape architect noted “the young oak leaves are a vivid yellow green, quite distinct from the gray and reddish greens of the northern oaks in the spring. At Manley was a brilliant blue and scarlet field of the common toadflax and the common sheep sorrel.”

It became something of a working holiday for Leonard Tufts, who diligently recorded his observations regarding the Capital Highway’s condition, and then submitted them for publication to local newspapers serving towns along the route. As the Reo neared Cameron that first afternoon, Leonard did not like what he saw. “From Pinehurst, the first seventeen miles of the road is good, the next four miles to Cameron the road is deteriorated as it has had little attention,” he wrote. “From Cameron to Lemon Springs, N.C., a distance of six miles, the sand is as deep as ever.” The excessive sand caused the Reo to be slowed to 5 mph. But when the road was in satisfactory repair, Leonard noted that too. “(F)rom Lemon Springs to Jonesboro, six miles, there has been some improvement. Jonesboro Township is to sell its road bonds this month, and then will put its part of this in first-class shape.”

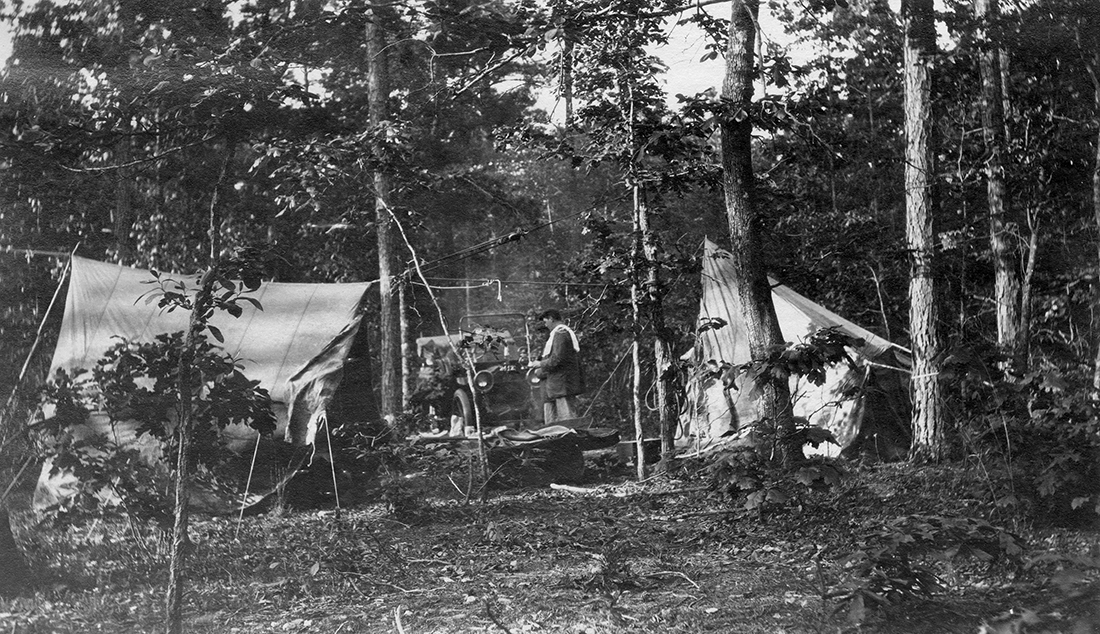

At 7 p.m., shortly after passing through Sanford, the four men pitched tents in an oak woods. Manning’s journal indicates that after setting up “4 cots, 4 sleeping bags, (and) the commissary boxes,” the four sat by the fire, ate supper, and went to bed. Toting along camping gear was pretty much a necessity for any long-haul motoring in 1911. With unforeseeable road conditions and the frequent breakdowns of the early vehicles, it was guesswork where one might wind up after a day’s driving. And because service stations and auto mechanics were few and far between, motorists like Tufts generally needed to be self-reliant in dealing with flat tires, engine troubles, and a wide array of other road mishaps. For early auto enthusiasts, the unpredictability of what might be encountered made for a challenging adventure.

The Reo certainly challenged Leonard. On the morning of May 7, he fiddled with the engine until 11 a.m. before it fired up. Once on the road, Manning noticed that Tufts was being especially considerate of carriage drivers and their teams of horses. The horses would sometimes rear when Leonard’s horseless carriage whizzed by. “Sorry to have given you all that trouble, sir,” Leonard would invariably say. According to Manning, his friend’s unfailing courtesy tended to “chase away frowns, and bring smiles and ‘thank-yous.’”

On that first full day of driving, Warren became aware of Charley Cotton’s unique brand of wisdom. Some of his maxims, though farcically illogical, made perfect sense. When a drowsy mule trudging by suddenly acted up, Cotton cautioned Manning that, “a mule . . . (may not) wake up until you get by him, but then, he wakes up powerful smart.” Tire troubles continued to dog the travelers that day, but they managed to reach Raleigh by late afternoon, where they gave the Reo “a feed and a drink in a garage.” The men set up camp outside the city on an abandoned road.

A “drizzly day and mud, mud, mud,” greeted the travelers the following morning (May 8), and progress was slow. Weary from the slog, they ended the day in Warrenton, North Carolina, only 55 miles from Raleigh. But spirits were high after Charley served up dinner of steak, strawberry preserves, bread, and a corn batter and flapjack combination.

The worst road conditions of the trip confronted the men on May 9, and Leonard informed newspaper readers all about it. “For the next eleven miles . . . through Macon and Vaughn to Littleton, the roads are bad and seem to me to be getting worse,” reported Tufts. “There was a man with a light car ahead of us, whose tracks we watched with a great deal of interest. We counted where he had gone into the ditch sixteen times, and then we quit. We were fortunate in going in only four times.”

The intrepid band negotiated the quagmire, and finally entered Virginia at 4:30 in the afternoon. Once having crossed the state line, Leonard found the highway much more to his liking. “When you come to Barley (Virginia) you strike the kind of roads you dream about, and your motor picks up its head, arches its neck and goes down the road like a two-year-old,” wrote the admiring Tufts. “It is sixteen miles of gliding. Three cheers for Greensville County, and their board, Messrs. Cato, Rainey, and Murfee.”

The men camped that evening between Emporia and Jarratt, Virginia, “near a railroad crossing in a tall pine grove,” close to “several Negro cabins.” According to Manning, a number of the African-Americans, “soon trooped over, headed by Mr. ‘Bologna Sausage’ (a moniker provided by Charley), who appeared again after supper, with his accordion to sing, play, and tell stories around the fire that lighted three white faces on one side, and five black faces on the other.” Leonard passed out cigars to all in attendance while Cotton “weaved in and out through the ranks and to the fire washing dishes.”

Manning reported that sleep came rapidly that night “in spite of the occasional trains . . . pig squeals, donkey brays, clank of a wall chain, and in the morning (May 10) a multitude of bird calls, Whip o’ will, chuck-will’s widow, chickadee, creepers, crowing roosters, and cackling hens.” Cotton’s tasty breakfast of steak and corn cake awaited Tufts, Manning and Marr. Once on the highway, Tufts piloted the Reo to Loco, Virginia, where he indulged in some road politicking with J.M. Tyus, whom Leonard praised as having “done more in the last two years with the limited money at hand than any man has done on the Capital Highway, in my opinion between Richmond and Augusta, Ga.” From there the foursome made good headway through Petersburg and Bensley, finally reaching Richmond, where “the auto went to garage for clean up, repairs, and food, and we to the Jefferson Hotel for the same.”

Having already decided not to follow the Capital Highway to its northern terminus at Washington, D.C., they took a westerly route up the Shenandoah Valley in the direction of Charlottesville. Of the 273 miles of the highway the men traveled from Pinehurst to Richmond, Leonard estimated that the road was poor for 73 of them. His newspaper article suggested the bad sections could “readily be put in good shape at an expense of not over $20,000,” provided “we all work together.”

The group was eager to move on from Richmond on the morning of May 11, but repairs to the Reo delayed their departure until 6 p.m. They were led out of town by “a pilot auto filled with Mr. Tufts’ auto club (AAA) friends, who went out a number of miles — miles of dust, too, for there were many machines on this part of the road.” Though it was the normal routine to set up camp before dark, this particular evening with its soft balmy air and full moon struck them as so “exquisitely delightful” that they continued motoring long into the night. Finally stopping at midnight, the men pitched their tents in oak woods “at the first railroad crossing beyond Louisa.”

The following morning (May 12), they drove to Charlottesville, where they toured Monticello and the University of Virginia. Relishing the Jeffersonian history and architecture, they whiled away most of the day before cranking up the Reo, ultimately setting up camp just 23 miles farther up the road in Afton, Virginia.

On May 13, Leonard had the Reo cover more than 100 miles as it steamed through Staunton and then Winchester (“a busy little city, not yet much modernized”). Manning did not much care for the frequent turnpike gates along the way, “to each of which fifteen cents is handed out in an envelope as we slow up a little.”

May 14 found the men in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where they viewed the battlefield monuments. The quartet camped at a grove located in Pennsylvania Dutch country near Myerstown. A Dutch farmer “with fire in his eye” approached the Tufts party, irate that the men were on his land. But when the farmer saw the Reo (still a rare sight in that area), there was an immediate about-face in his attitude. “My that’s a big automobile,” he marveled. Tufts and his contingent were permitted to stay.

On May 15, the men entered New Jersey. Notwithstanding the fact that the Reo was registered in North Carolina, Tufts was nonetheless required to obtain a separate New Jersey registration. Manning observed that the roads in New Jersey were uniformly good, however, when the travelers approached the Hudson River, there was no bridge available, and the four men and the Reo were ferried across to Tarrytown, New York.

Having spent 10 days in his company, Manning had become greatly impressed with Cotton’s ever-positive attitude. He considered Charley’s unfailing smile, displayed even during hard going through the mud, as the foursome’s “most valuable asset.”

The travelers finally reached New England on May 16, and with good roads and weather, made good time. After two days of driving, the group set up their last campsite in Hillsboro, New Hampshire. Then, on the afternoon of May 18, 12 days after departing Pinehurst, Tufts chugged the Reo up the driveway of his Meredith home, overlooking the breathtaking Lake Winnipesaukee.

Manning was stunned by the vista, writing that, “at no point have we seen a view that will conjure up the extent, variety, and beauty of lake, valley, and mountains . . . that Mr. Tufts secures from his summer home.” After enjoying a sumptuous feast, their great excursion was at an end.

While the men undoubtedly savored their shared adventure, the motor trip had a practical benefit. Tufts successfully used it as a means to rally county officials to step up support for the Capital Highway. Within a few years, visitors from the North, regardless of their city of origin, were traveling over a well-maintained highway to Pinehurst.

What became of the four wanderers?

There’s precious little information regarding Charley Cotton, though we know from Richard Tufts’ writings that Charley enjoyed the high regard of the entire Tufts family. Dr. Marr’s medical career lasted another 47 years before he retired from the staff of the Moore County Hospital in 1958. He also came to public attention when he testified in 1935 at an inquest regarding the mysterious and controversial death of hotel heiress Elva Statler, who had been his patient. He died in 1972 at age 91.

Manning achieved something akin to legendary status in landscape architecture, both in Pinehurst and nationally. He was integral to the formation of the American Society of Landscape Architects, and was a vigorous advocate for the National Parks System. He collaborated with Leonard Tufts for another two decades on projects, including the Knollwood development and the state fairgrounds. The two men also continued to work together on roads, though they were not always of the same mind as to how far into the future a road designer should plan.

Manning thought it best to engineer roads of sufficient width to accommodate many future generations of motorists. Tufts viewed the issue more conservatively. “I have been thinking about your wide road business,” Leonard wrote Manning in 1923. “We have 100,000,000 (population in the United States) now and an automobile to about every two families. While the present road system in Moore County is adequate for at least twenty times the traffic as far as the width of the road is concerned, I cannot conceive of a condition where there is more than one car to every family . . . and neither can I conceive of the population . . . doubling in less than twenty years. If my figures are right, this is planning for the next 80 years, and by that time we may have given up the automobile and gone to the air.”

Around 1929, Leonard, suffering from frequent bouts of ill health, began ceding control of Pinehurst’s affairs to son Richard. Leonard Tufts died in 1945. Though 36 years younger, Richard came to like and respect Warren Manning, and the two men partnered together on numerous projects. And, like his forebears James and Leonard, Richard had trouble keeping up with the still-spry Manning, who kept on speed-walking until shortly before his death in 1938. On one occasion when Richard was lagging behind, Manning turned to him and remarked, “Years ago I used to walk your grandfather off his feet, then I walked your father off his feet, and now I am walking too fast for you!” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.