Reclaiming Weymouth’s literary legacy

By Stephen E. Smith

It was as if, for a moment, I could remember the future.

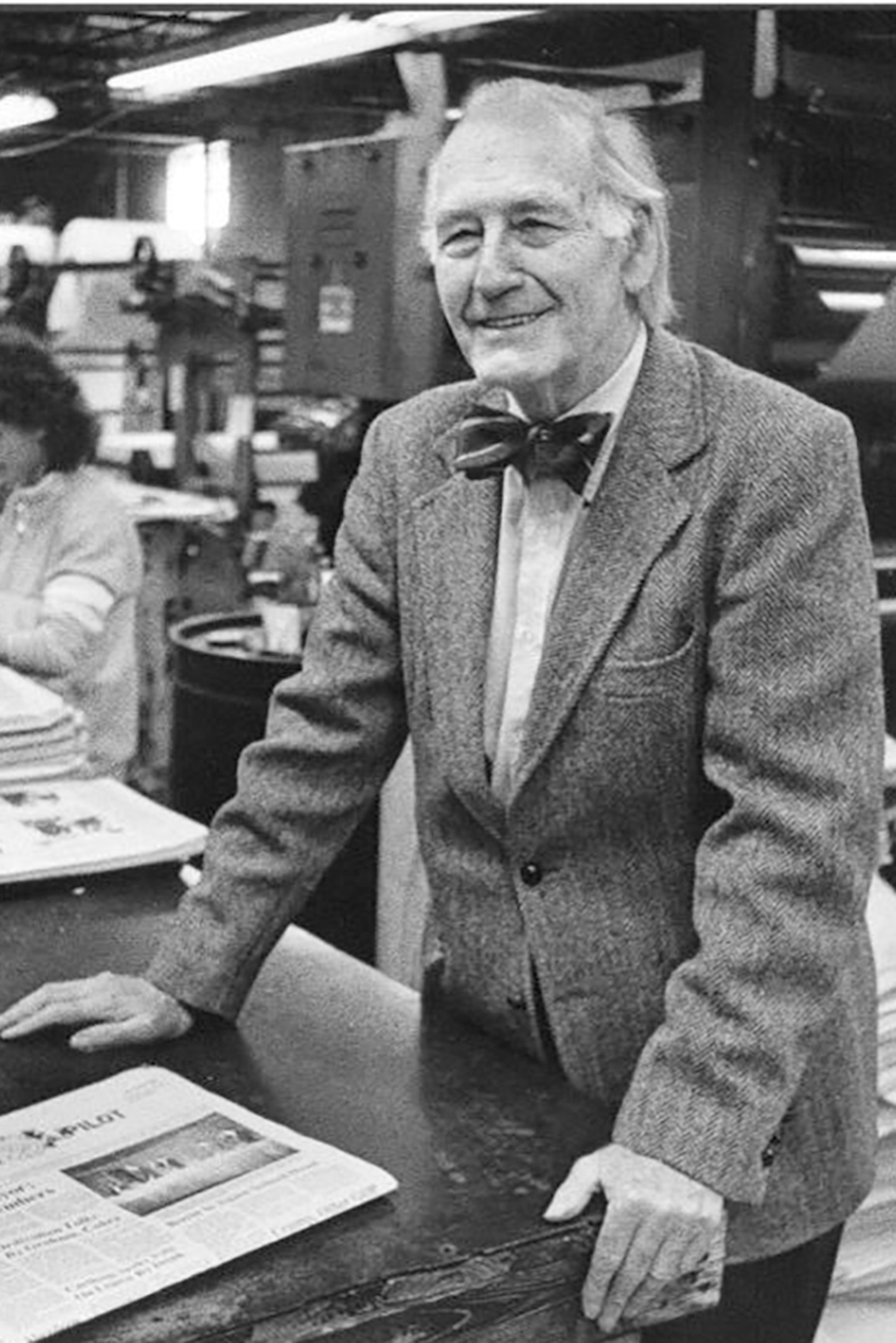

I’d just left Sam Ragan’s office at The Pilot where he’d chatted with me, a cigarette pinched between his thumb and forefinger, from behind stratums of desktop paper about his plans for the Boyd House, the former home of novelist James Boyd and his family. He mentioned that F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe and Sherwood Anderson, mainstays of our literary canon, had visited there and how he intended to establish a writers’ retreat in the old house, a sanctuary where North Carolina authors could work in peace and quiet and relative seclusion. He suggested I drive to the house, wander through the rooms and imagine the possibilities.

I parked my car in the weedy yard of the house on Weymouth Heights, stepped inside the foyer and climbed the stairs to what had been James Boyd’s study. In 1977, the space was being used by Sandhills Community College as a classroom for respiratory therapy students, and banks of florescent lights dangled from the plaster ceiling, and Formica-topped metal desks were scattered haphazardly on the old plank floors. But Sam had given me an intriguing taste of the house’s history, and taking in the scene I could imagine, for a moment, the room decades in the future, again populated by writers. What amazes me these many decades later is that it all happened just as Sam said it would.

At the time of my first visit, I found the house in dire need of repair. Sam might have hoped for an illustrious future for the dark paneled library, the twisting hallways with their random two-tread steps, the haphazardly situated bedrooms — an architectural puzzle pieced together from mismatched parts — but the house might just as easily have been razed and a high-dollar subdivision erected on the valuable property.

Plaster was crumbling. Paint was peeling. Pipes were clanking. The once-elegantly furnished great room was piled high with institutional furniture. But despite a half century of heavy use and the jumble of educational paraphernalia, there remained a romantic aura about the place: Blue-green sunlight slanted through the great room’s French doors and played on the worn, wide pine flooring. The filigreed plaster ceilings and grooved woodwork retained their charm, suggesting that wonderful things had happened there and would again.

Sam Ragan, Buffie Ives, Paul Green, Norris Hodgkins and other writers and community leaders banded together to form the Friends of Weymouth. They selflessly donated their time and money and raised the funds to purchase the property — and they immediately set about transforming the Boyd House, renaming it the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities, into the writers’ retreat Sam had envisioned. I was present, along with my friend Shelby Stephenson, at a few of the meetings in Weymouth’s dining room, where the physical and financial logistics of the undertaking were discussed. These informal gatherings were blessedly brief, no more than general affirmations of the plans Sam had contrived, and after all these years, I remember only one specific exchange verbatim.

Guy Owen, author of The Ballad of the Flim-Flam Man, was a guest at the meeting, and he happened to joke, “We should house the pornographic writers in the stables.”

Buffie Ives, Adlai Stevenson’s sister, sat up straight and snorted, “There’ll be no pornographic writers at Weymouth!” Buffie was a woman of strong opinions, an adamant local preservationist, and she meant to have her way.

Rooms were painted, beds donated, the house adequately spruced up, and literary folk began to apply for residencies. The first writers to make use of the Weymouth Center were Guy Owen and poets Betty Adcock and Agnes McDonald. Sam asked me to welcome them on their arrival — I knew all three from the North Carolina Writers Conference — and to make them feel at home, which meant I should leave them to their writing.

As planned, Guy and Agnes left after a week, and Betty stayed for another five days. She was alone in the big empty house with its creaks and groans, the windows rattling as Fort Bragg grumbled in the distance. After a few hours spent in solitary, she phoned me to ask a favor. “May I sleep at your house?” she asked. “I just can’t be here all by myself.”

I’d known Betty for five or six years, and my wife and I considered her a close friend, so for a week, I drove to Weymouth at sundown so Betty could sneak out to spend the night at my house. At dawn, I’d drive her back to Weymouth, and she’d slip into bed so it would appear, if someone happened to check on her, that she’d been sleeping peacefully through the night.

It wasn’t long before word spread in the North Carolina writing community that residencies were available at Weymouth, and writers began to apply with surprising frequency. I’d like to claim I knew every writer who turned up at the back door, and in the beginning of the program that may have been true — North Carolina writers were a tight bunch in those days — but as the state has grown, a deluge of scribblers has descended upon Weymouth to partake of its storied enchantments, which are no doubt more the product of hard work than mystical thinking or encounters with resident spirits.

Tucked in a file cabinet at the Weymouth Center is a partial list of writers who’ve been in residence, but for many of the early years we kept no accurate record of who occupied the house and for how long. It’s safe to say that there have been hundreds of residencies, not counting return visits. Almost every North Carolina writer of any note has written or offered a public reading at Weymouth: Clyde Edgerton, Fred Chappell, Lee Smith, Bland Simpson, Reynolds Price, Wiley Cash, Tom Wolfe (The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test Wolfe), Tim McLaurin, Robert Morgan, Margaret Maron — and too many others to mention here.

For the first 40 years of Weymouth’s existence, I served on the board or the program committee with other volunteers who were devoted to maintaining Weymouth (the house requires constant upkeep) while providing lectures, performances and readings of interest to the community. Weymouth has hosted hundreds of public programs and private gatherings — classical concerts, plays, dance performances, lectures, fundraisers, club luncheons, Poetry Society gatherings, business meetings, holiday celebrations, formal cocktail parties, poetry readings, pig pickings, North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame inductions, songwriting workshops, square dances, and hundreds of gatherings that simply marked the joys of life, great and small.

On a spring evening I might enjoy the Red Clay Ramblers in the great room; a month later I might be listening to brilliant classical guitarists perform in the same space. I heard Doc Watson pick “Black Mountain Rag” on the terrace, and a rock band kick out the jams on the front lawn a week later. Weymouth has provided the state and the Sandhills community with a public venue that has imbued each event with an air of intimacy and import.

I admit that when I first stepped inside the Boyd House in 1977, all I knew about James Boyd was what I’d read on the state historical marker on the corner of Vermont and May, but by the early ’80s I’d read Boyd’s novels (no easy task), and that set me on a personal quest to discover everything I could about the Boyd family.

In the ’80s and ’90s, I visited the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill on at least 10 occasions to read the Boyd letters, an experience that opened up the family’s lives as an epistolary narrative — their ambitions, internal conflicts, and their abiding regard for one another and their fellows. I admired the letters James wrote to Katharine during World War I, when he was stationed in France with the Army Ambulance Corps. His affection for his young wife is palpable in his sentimental use of language. I held in my hands letters written by Fitzgerald, Wolfe, Anderson, Hemingway, Paul Green, Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins, and many other literary figures.

In the mid-’90s, I traveled to the Firestone Collection at Princeton University to read the Maxwell Perkins papers, and there I discovered a stack of correspondence between Boyd and Perkins. There were also letters from Wolfe and Fitzgerald concerning their relationships with Boyd.

I was particularly moved by a letter from Katharine to Perkins written after James’ success as a novelist had waned. She asked Perkins not to reveal to her husband that she’d written, but she implored him to write James a letter of encouragement so that he might overcome the writer’s block he was experiencing.

In the ’90s, I interviewed Jim Boyd, James and Katharine’s surviving son, about his life in Southern Pines. He recalled with amusement his meeting with Thomas Wolfe — “He climbed in through an open window in the middle of the night and fell asleep on the couch; I found him there when I came downstairs in the morning. . . .” — and he was forthright about his relationship with his mother and father and their literary friends: “These were people who were drinking martinis at 10 in the morning.”

More than four decades of working with Weymouth has stuffed my head with too many memories to recount them all here. Lord knows how many names I should have mentioned but didn’t. Rest assured that it’s not from lack of regard for their good works and personal sacrifice. I honor the Dirt Gardeners, the Women of Weymouth, and all the committee members who have come and gone. Every one of them is his or her own historian; they all have a story to tell — and they should tell it. The history of Weymouth has thousands of authors.

My final judgment is that the Boyd House/Weymouth Center for the Arts and Humanities is, without question or qualification, a community masterwork, an example of what well-meaning and determined volunteers can achieve when toiling for the greater good. Maybe our children and grandchildren will know this, for it seems probable to be the best version of these tragic times which we will pass along to them.

A few years ago, I was in the Great Room participating in a song circle where each player offers a tune or two. When it was my turn to play, I announced: “Eighty years ago this evening, F. Scott Fitzgerald was sitting in this room discussing the art of the novel with James and Katharine Boyd and Struthers Burt and his son.” The faces of my fellow players went blank. Fitzgerald, smitzgerald, they seemed to say, play your guitar already. Only then did I realize that they were doing what I had done: They were thinking about the song they were going to sing — the story they could one day tell about their performance at Weymouth. They were remembering the future. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.