Johnny Allen and the Aberdeen Nine

When an all-time great wore an “A” on his chest

By Bill Case

In 1956, at age 7, I fell madly in love with baseball. That summer, and several ensuing ones, I spent an untold number of daylight hours playing both organized and pick-up baseball, as well as the game’s myriad offshoots — pepper, home-run derby, monkey in the middle, etc. After hurrying through dinner, I would often spend another hour hurling a ball at a target painted on the basement wall and fielding the rebound. With an accompanying radio broadcast of a Cleveland Indians (aka the Guardians) game providing grist for my overactive imagination, I would visualize myself playing second base for Cleveland while backhanding countless caroms off the wall.

None of the Indians’ players resided in my hometown of Hudson, Ohio, 26 miles from Cleveland, but the team’s longtime trainer, Wally Bock, did. My parents, Bea and Weldon Case, knew Wally and his wife, and asked them over for dinner. I could not have been more excited if Cleveland’s Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller had been invited.

When the Bocks arrived at our home, Wally tossed me a ball (which I still have) autographed by all the ’56 Tribe players. But, too soon, Mom and Dad ordered me upstairs to my room. While lying restlessly in bed, I hatched what in retrospect was a ridiculous plan: Wouldn’t it be cool to finagle a rubdown from Wally like the ones he once administered to Feller and the other Indians I idolized? So, I yelled downstairs, “Mom, my back really hurts!”

My crying wolf fooled no one; nonetheless, the scheme worked. With my folks looking on and shaking their heads at my transparent ploy, Wally provided a brief backrub. All fixed. So, much like Bill Murray’s character Carl Spackler who was promised “total consciousness” by the Dalai Lama in Caddyshack, I got that going for me.

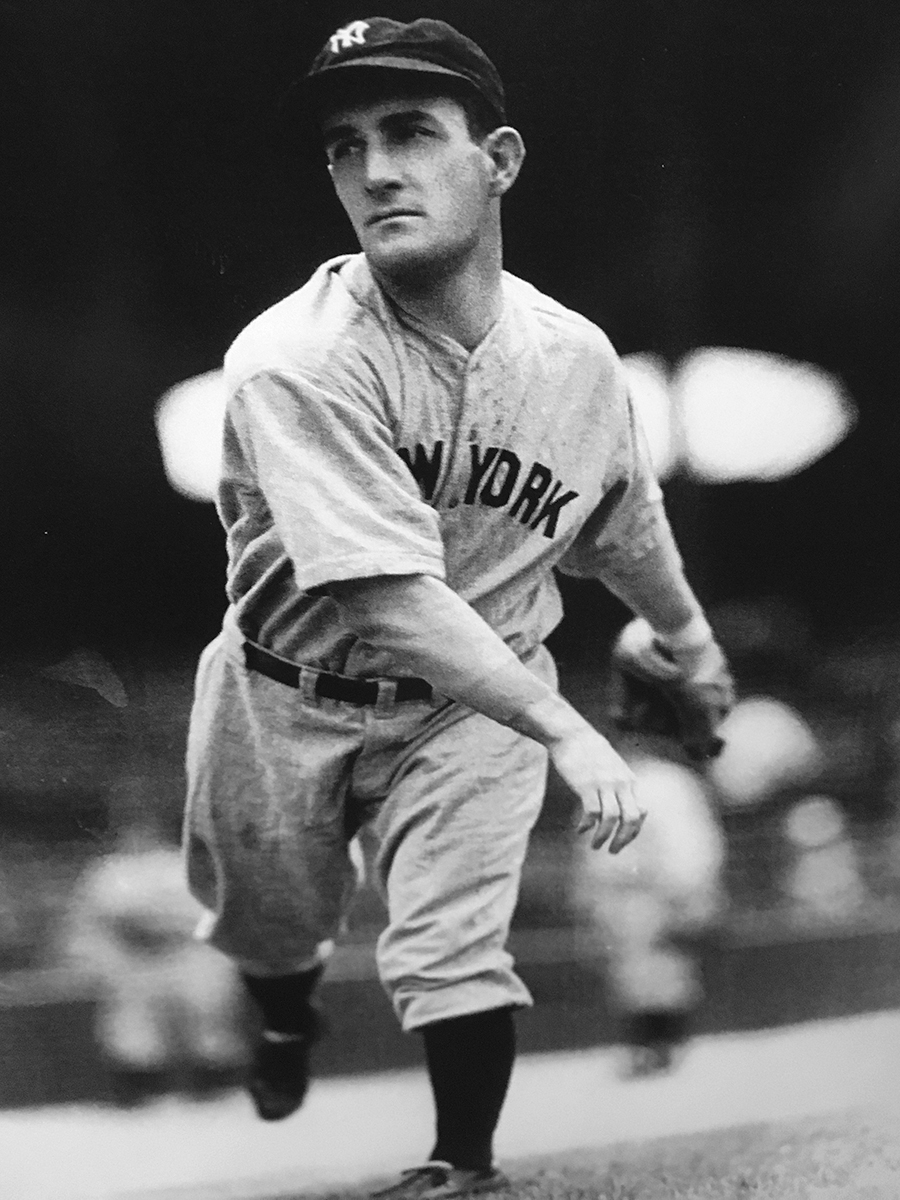

My baseball passion extended to the game’s vast array of statistics. Without attempting to, I committed to memory countless batting averages and home run totals. One mark that always stuck with me was pitcher Johnny Allen’s 1937 win-loss record of 15-1. His resulting winning percentage of .938 was, at the time, a major league record.

The mark was ultimately bettered by Elroy Face’s 18-1 for the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates in 1959, but to this day, Allen holds the American League record. No pitcher in the 146 years of major league history has posted an undefeated season with at least 15 decisions — the minimum number required to qualify for the winning percentage title. More astonishing is the fact that Johnny was undefeated until the meaningless final game of his ’37 campaign. Risking the unblemished record, he took the mound against the Tigers with just two days of rest. Allen lost 1-0, the lone run scoring in the aftermath of an error by Indians’ third baseman Odell Hale. According to an online post by the Society for Baseball Research, an infuriated Allen “went ballistic after the game” and twice had to be restrained from assaulting his third baseman.

Such behavior was not out of the norm for the hyper-competitive hurler. His 13-year major league career (1932-1944) with the Yankees, Indians, St. Louis Browns, Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants was replete with similar incidents. He was known to throw furniture in the clubhouse, but his piques of wrath weren’t confined to the ballpark. After a tough loss to the Red Sox, an enraged Allen returned to the team’s hotel, upended stools in the bar, kicked over an ashtray of sand, and sprayed a corridor with a fire extinguisher. In 1943, it took several teammates to restrain Allen after he rushed an umpire “like a wild man” after the ump called a balk on him. When another unfortunate third baseman cost Allen a game by dropping a pop fly, the pitcher decked him in the clubhouse, then announced to his startled Yankee teammates, “If anybody else drops an easy fly on me, that’s what’s going to happen to you.”

In a notorious 1938 controversy, umpire Bill McGowan ordered Allen to remove the sweatshirt he wore underneath his jersey after the pitcher had cut strips out of the sleeves to “improve ventilation.” Distracted by the fluttering fabric, opposing hitters complained. Allen refused to change his shirt and huffily stalked into the clubhouse, defying Indians’ manager Oscar Vitt’s directive to return to the mound. Allen was fined but recouped his money by selling the sweatshirt to a downtown Cleveland department store, which proudly displayed it in its storefront window. Today, the garment is an exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

While his competitive fire could land Allen in hot water, it no doubt contributed to his pitching greatness. His near undefeated season in ’37 merited his selection by The Sporting News as that year’s Major League Player of the Year. His career winning percentage of .654 (142-75), ranks 22nd best all-time. Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey described Allen’s sidearm fastball as “the meanest delivery in the league for a righthanded hitter. He’ll buzz it over the bat handle before you can see it.”

A second Hall of Famer, Al Simmons, picked Allen as the toughest pitcher to hit against in that slugger’s 20-year career. Allen’s record might have been even more impressive had he not been plagued by a sore arm his last six years in the majors.

My fascination with stats like Allen’s 15-1, and for baseball itself, cooled substantially at age 13 after I failed to crack the starting lineup and quit the local little league team, the Hudson Hornets. I stopped buying baseball cards and no longer paid rapt attention to the exploits of legends like Feller and Ted Williams, let alone those of less remembered stars like Johnny Allen.

But two years ago, Allen came to mind again when I came across a short 1935 piece in The Pilot, reporting that Allen “who used to clerk in the Aberdeen Hotel, is going great guns for the New York Yankees” and that, during this employment, circa 1926-27, Allen pitched for the local Aberdeen team that competed in the Moore County Baseball League.

A search of the archives of The Pilot and the defunct Moore County News failed to unearth further references to Allen’s days here, but Wint Capel’s biography of Allen, Fiery Fast-Baller, published in 2001, provided some additional details about the pitcher’s pre-major league wanderings.

Born in Lenoir, North Carolina, in 1905, Allen, like his Yankee teammate Babe Ruth, spent the bulk of his youth in an orphanage, playing both infield and outfield positions for the Thomasville Baptist Orphanage baseball team. Capel writes that there “was no hint that he would become a sensational big league pitcher.”

While at the institution, Johnny suffered a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was resting the muzzle of a 12-gauge shotgun on the toes of his shoe when the gun accidentally discharged, causing the loss of two toes on the teenager’s right foot. (Another great North Carolina pitcher, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, also suffered a shotgun injury to his right foot when he was a teenager, losing one toe.) Though he chafed at the orphanage’s strict regimen — making frequent attempts to run away — Allen did learn the basics of the bookkeeping trade there. It was expertise enough to secure a night clerk position at Greensboro’s O.Henry Hotel following his 1922 release from the orphanage.

According to Capel, Allen drifted from one hotel clerking job to another, “for a change of scenery as much as anything,” serving brief stints at the Monticello Hotel in Charlottesville, Virginia, the Sheraton in High Point, North Carolina, and the Wildrick Hotel in Sanford, North Carolina. While working at the latter establishment, he got back into baseball, playing on a local church league team.

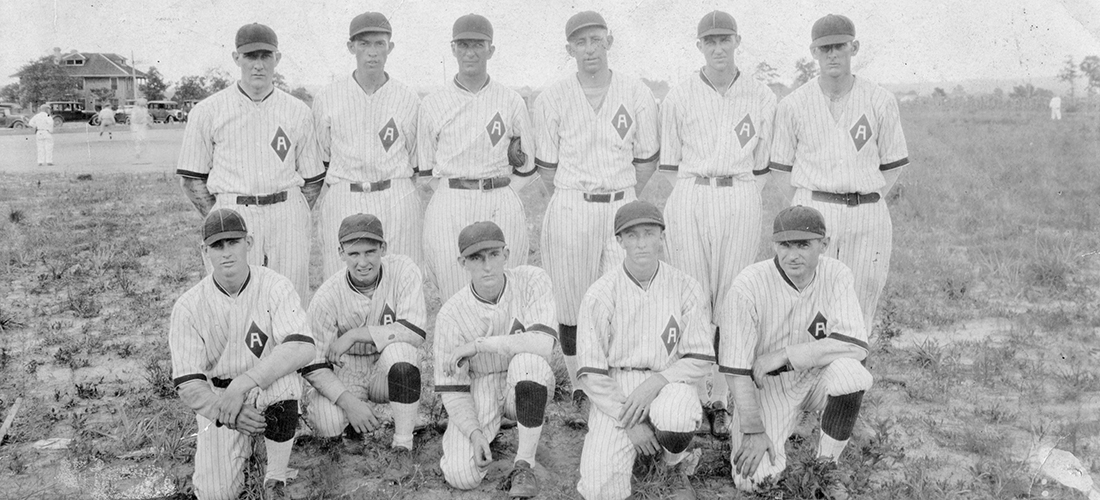

In or around 1926, Allen pulled up stakes again, moving to the Sandhills for a clerking position at the Aberdeen Hotel, and soon joined the town’s semi-pro baseball team.

The 23-year-old Allen left Aberdeen in 1928 to play “organized baseball” with the Greensboro Patriots of the Class B Piedmont League. During that season, he also pitched for teams in Fayetteville, Greenville and Raleigh. In 1929, he signed with the Asheville Tourists, where Johnny Nee, a scout for the New York Yankees, saw him and, impressed with his blazing fastball, signed the 24-year-old to a contract.

After two years of seasoning with Yankee minor league affiliates Allen joined the mighty Bronx Bombers in 1932. The manager was the great Joe McCarthy. His teammates included Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth and Bill Dickey. In that rookie campaign, he logged a sparkling 17-4 record and pitched in the World Series where the Yanks defeated the Chicago Cubs in four games.

After three more seasons in New York and five in Cleveland, Allen was dealt to the St. Louis Browns, something that was dutifully noted in a 1940 issue of the Pinehurst Outlook. Jerry V. Healy’s story included a recounting of Allen’s initial appearance 14 years earlier for Aberdeen. Pitching against “the strong Mt. Gilead nine on the latter’s local grounds,” a disastrous outing “almost ruined Allen’s career.” As Healy put it, “the farmer boys up in that section loved nothing better than to hit a fast ball a country mile, and Johnny had a fast ball. The coming star (Allen) was retired in short order.”

After his catastrophic debut, Healy noted that Allen, “quiet and peaceful in those days,” eventually starred for Aberdeen. “Wild as a hawk, he won many games by the mere effort of scaring opposing batters away from the plate,” Healy wrote. Allen’s lone shortcoming was “his slow and stumbling baserunning,” no doubt caused by the injury to his foot. Allen made up for this deficiency by smashing home runs and extra-base hits.

The article also mentioned Allen’s link to Jack Meador, “the present manager of the Aberdeen Hotel,” which had previosly employed Johnny. Moreover, in 1928 the hotelman had moonlighted as the Fayetteville Highlanders’ secretary-treasurer during Allen’s brief time on that team. Several months after Healy’s article was published, a massive fire consumed the Aberdeen Hotel. A new hotel was constructed on the same site and renamed the Sandhills Hotel, with Jack Meador remaining in charge. The new structure burned down in February 1942, and Meador lost his life attempting to rescue guests from the blaze.

The Aberdeen team photo accompanying Healy’s article identified Allen and all his pinstriped teammates. According to longtime Aberdeen Mayor Robbie Farrell and his sister Betsy Farrell Ingraham, virtually all the Aberdeen players shown in the picture became men of prominence in the community. Gordon Keith owned the town’s dry-cleaning business and also won the 1939 golf championship of the Southern Pines Country Club. Gordon’s brother, Kenny Keith, was the town’s go-to carpenter. Billy Huntley owned substantial real estate in the area, including the local drive-in theater. Max Folley’s family ran the lumberyard. Bill Maurer was active in the tobacco markets and became co-owner of the Aberdeen Warehouse. Hughes Bradshaw operated a gas station. John Duncan McLean owned the local hardware store and served as Aberdeen’s mayor.

Arnold “Bony” Ferree served as a health inspector, while his brother, Purvis Ferree, achieved fame in Winston-Salem as the longtime golf pro at Old Town Club. Purvis became the first person inducted into the North Carolina Golf Hall of Fame. His son, Jim Ferree, would continue the family’s golf legacy by winning a pro tour event (the 1958 Vancouver Open) and was the beknickered, silhouetted model for the PGA Champions Tour logo. Finally, George Martin owned Martin Motors, the town’s Buick dealership, on South Street, now a church. Martin installed a bank of showers inside the dealership so that his teammates would have a place to wash up after games.

Gordon Keith’s son, David Keith, now lives in Cameron. His irrigation contracting business is in the old family house on Keith Street in Aberdeen. Born after his father reached 50, David is only in his 60s. He remembers his father saying that Allen was a “ringer” — paid money, presumably raised by the passing of a hat at games, to pitch for Aberdeen — and that his father often served as Allen’s catcher. The games were on Wednesday afternoons, the day many area businesses closed at noon, and attracted sizable crowds. (The Aberdeen Supply Company closes on Wednesday afternoons to this day.)

David Keith still has an ancient, scuffed baseball with links to the old Aberdeen nine. It was given to him years ago by his best friend, Sam Buchan, a grandson of the aforementioned George Martin. Buchan got the ball from Martin’s teammate John Duncan McLean. Mayor McLean kept the ball, belted for a home run in a Moore County League championship game, as a piece of local memorabilia. Just a few years ago, the ball was among the possessions stolen from Keith’s house in a robbery. Fortunately, the perpetrator was caught and the treasured ball returned.

While The Pilot did little to cover the activities of the Moore County Baseball League, the 1932 season was a notable exception. That year, the Aberdeen team found itself in the thick of the race for the league title. Several of Allen’s old teammates from the ’20s were still mainstays on the squad, including Martin, Max Folley, Purvis Ferree, Bill Maurer and Billy Huntley. To reach a playoff series against Vass-Lakeview for the league championship, Aberdeen needed to beat Southern Pines in the last game of the regular season. The deciding contest was played the last day of August on Aberdeen’s home field, now the site of Cactus Creek Coffee.

The county was abuzz, the game looming larger than even the upcoming World Series in which Johnny Allen would appear. When game day arrived, the ballfield was packed. “Two thousand or more people from every corner of the county gathered around the Aberdeen diamond for Wednesday’s big game,” reported The Pilot. “It was the climax of a thrilling baseball season. Aberdeen and Southern Pines were deserted. Everybody was at the ballpark.”

As Aberdeen’s player-manager, George Martin sent himself to the mound for the pivotal game. Inspired by the massive crowd, he pitched brilliantly, shutting out Southern Pines, 6-0. But it wasn’t Martin’s fastball that had turned the trick; it was his out-of-the-past, good luck garb. “George had put on his 1921 uniform. Of course! That explained all,” wrote The Pilot reporter. “You remember George Martin back in 1921. Burning ’em in. Foe to every opposing batsman. Striking ’em out with his change of pace. George in his 1921 clothes! What chance had Southern Pines?”

Aberdeen went on to defeat Vass-Lakeview three straight in a best-of-five series, breezing to the league championship. Playing a nifty first base, Martin contributed multiple hits in each game, including a tide-turning homer in game two — likely the ball now in the hands of David Keith. The Pilot attributed much credit for the series victory to Martin. “He not only guided his men well, but proved an example in the field and at bat, playing errorless ball and hitting with the best of them.”

Five years later, Martin died suddenly while working at his desk. He was just 36. The Pilot described him as one of “Aberdeen’s most beloved citizens,” and that he would always be remembered for his baseball accomplishments — especially the memorable ’32 game he pitched and won in a 1921 uniform.

“You should talk to Kam Hurst, George Martin’s granddaughter,” David Keith said. “I think she has his uniform.”

Hurst’s grandparents had lived on Pine Street in Aberdeen in a home Martin built in 1923. After he died in 1937, his widow continued to reside in the house for many decades. After Hurst’s grandmother’s death, the house remained in the Martin family. While making repairs in 2009, Kam and her husband, Ricky, spotted her grandfather’s long forgotten baseball gear in the attic, undisturbed since his death 72 years earlier.

Inside a timeworn black duffle were Martin’s cleats, still sharp enough to dig into a basepath, his glove — little more than a primitive leather slab — and a cap bearing the red letter “A.” Separately, there was George’s wool uniform, still wearable. The pinstripes, however, didn’t have the “A” insignia affixed to the players’ jerseys in the ’26-’27 team photo. This had to be George Martin’s 1921 uniform.

While Martin’s heroics highlighted the rousing finish of the Moore County League’s 1932 season, the eight team league didn’t last much longer. It would disband in 1934. The four-team Sandhills Baseball League tried to fill the vacuum, but with the Great Depression raging, it was difficult to cajole financially struggling spectators to drop money into a passing hat. A Memorial Day All-Star game that attracted a crowd of 500-600 resulted in paltry receipts of $14. Semi-pro baseball in North Carolina was beginning a gradual fade-out.

Also on the wane was Johnny Allen’s playing career. His final major league season in 1944 was the only one in which he recorded a losing record. He stayed in the game, however, becoming a minor league umpire. Once the bane of the “men in blue,” Allen became the chief ump of the Carolina League. He gave up the job in 1952, thereafter buying and selling real estate in St. Petersburg, Florida.

When not on the mound, Johnny Allen was personable, a good husband and father, and a generous contributor to charities, including the orphanage of his youth. While he could be nasty to those who cost him victories, in the fullness of time he claimed he mostly got sore at himself “because I think of a million and one things I could have done in the situation and didn’t do.” There may have been a third baseman, or two, who would be less generous.

Allen died in 1959 at the age of 54. Enshrined in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 1977, he was later named one of the best 100 players in the history of the Cleveland Indians. A ranking of the best baseball players born in North Carolina places him fifth. The four in front of him are in the Hall of Fame.

John Allen III, who lives in St. Petersburg, Florida, believes his grandfather should be recognized among baseball’s all-time greats, but is not, “because he didn’t kowtow to the press. In fact, he went out of his way to tell them how little respect he had for them. Boy, do we need more of those type of men today.”

While Johnny Allen’s relative standing in the ranking of baseball greats may be subject to debate, it is undisputed that he is the greatest ballplayer ever on a Moore County team. His exploits here — and those of George Martin on long ago Wednesday afternoons — become less ephemeral after laying eyes on relics like Martin’s glove, uniform, spikes, and the ball he smashed for a home run.

As James Earl Jones’ character Terence Mann reflected in Field of Dreams, baseball appeals to our longings for the past. “The one constant through all the years has been baseball . . . It reminds us of all that once was good and it could be again.”

It reminds us of a target on a basement wall. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.