The secret in the Sandhills

By Bob Curtin • Photographs from the Moore County Historical Association

It’s possible to jump on your Harley or crawl into your Subaru and drive from Southern Pines to Laurinburg on U.S. 15-501 as if you’re heading to Myrtle Beach for a game of skee ball and some Calabash seafood and never know you’ve just passed one of the U.S. Army’s more secretive military training installations.

Camp Mackall, built almost overnight during World War II to train paratroopers and glider units to invade France, is today a primary training facility for elite Special Forces, the Green Berets. What’s secretive isn’t so much that they train, it’s how they train, turning seasoned, professional soldiers into highly skilled, well-conditioned and formidable Special Forces soldiers. The modern Camp Mackall encompasses about 8,000 acres of land, composed of eight major training sites, and every Special Forces soldier who earned the right to wear the Green Beret has left his sweat and blood in those forests and fields.

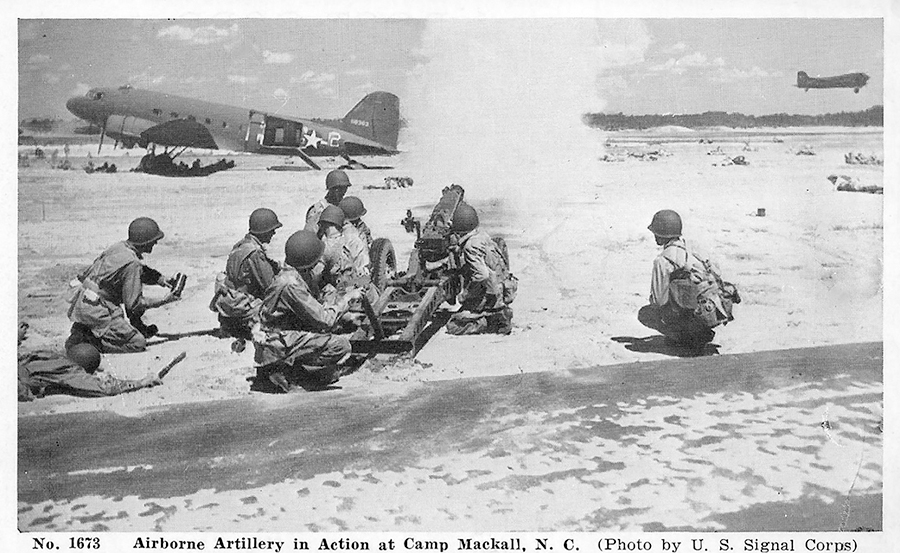

During World War II Camp Mackall trained and tested division-size airborne forces in combat operations. In 1943 it was home to three newly formed units of the 11th, 13th and 17th Airborne divisions. The 82nd and 101st remained garrisoned on Fort Bragg but trained at Mackall. Today, our Green Berets are often referred to as the proverbial “tip of the spear” and operate in the dark of night and well behind enemy lines to perform almost superhero-like missions. During WWII, our newly formed airborne paratroopers would have been considered card-carrying members of the tip of the spear club.

Originally named Hoffman Air Borne Camp, on Feb. 8, 1943, the installation was renamed in honor of Pvt. John Thomas (Tommy) Mackall. During the Allied invasion of North Africa, in the airborne maneuver named Operation Torch, Mackall was mortally wounded during an attack on his aircraft as it landed. Seven paratroopers died at the scene and several more were wounded, including Mackall. He was evacuated to a British hospital, where he died of his wounds on Nov. 12, 1942. Mackall was listed as the first American airborne fatality of WWII.

Training the five airborne divisions in the newly formed United States Army Airborne Command was going to require space, and lots of it, for both parachute and glider operations. The United States Department of War began planning construction of Camp Mackall as early as 1942. The land south of Southern Pines was ideal because the federal government already owned a large parcel of it. Construction plans called for an installation that could house and train up to 35,000 soldiers. By comparison the entire population of Moore County in 1940 was slightly over 30,000.

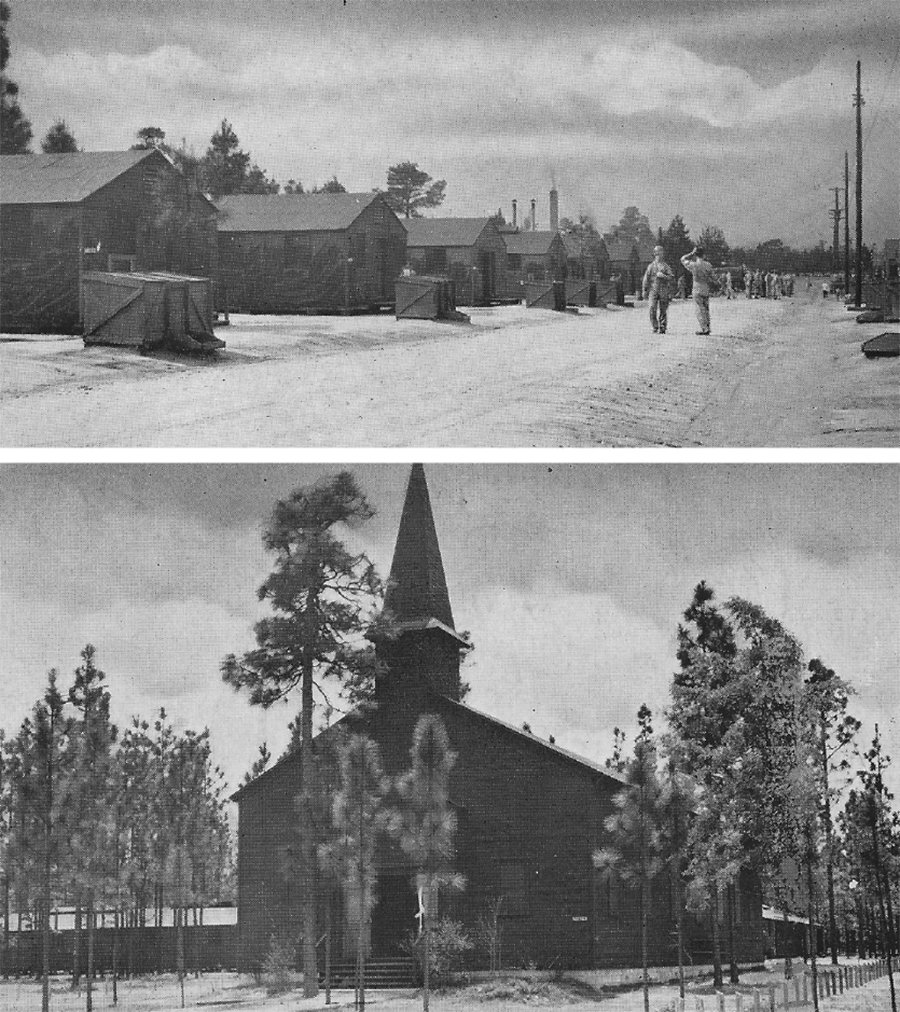

In just over three months, more than 62,000 acres of game land and leased farmland were transformed into a bustling military city. The camp included 65 miles of paved roads and several hundred miles of hard-packed trails capable of moving both civilian and military vehicles to the 1,750 buildings within the garrison’s north and south cantonment centers. The camp garrison provided housing for camp cadre, airborne trainees, as well as the paratroopers assigned to the airborne divisions. There were barracks, unit headquarter buildings, three libraries, six beer gardens, 10 barracks-style chapels, entertainment, fitness and sports facilities, and a triangular-shaped airfield with three 5,000-foot runways.

Built with wood and tarpaper, the buildings were hot in the summer and cold in the winter. In the worst of the heat, the soldiers propped opened the doors at both ends of their barracks, either praying for the mildest of breezes or requisitioning (legally or by any means necessary) large floor fans. The biting cold of the winter months was more dangerous. The buildings were equipped with pot-bellied, coal-burning stoves, and soldiers had to take special precautions — even attend courses and post a 24/7 guard force — to avoid burning down the wood and tarpaper boxes.

Besides the tarpaper-covered barracks that dotted the landscape, there were some larger and more permanent buildings — movie theaters, churches and headquarters — constructed with brick and mortar. Five theaters showed the latest Hollywood movies. There were 10 wood and tarpaper chapels and two large brick churches, manned by 28 chaplains of many denominations. According to Tom MacCallum and Lowell Stevens, authors of Camp Mackall North Carolina: Its Origin and Time in the Sandhills, “The communities of Southern Pines, Aberdeen, Pinehurst, Rockingham, and Hamlet embraced the paratroopers’ faith based needs.”

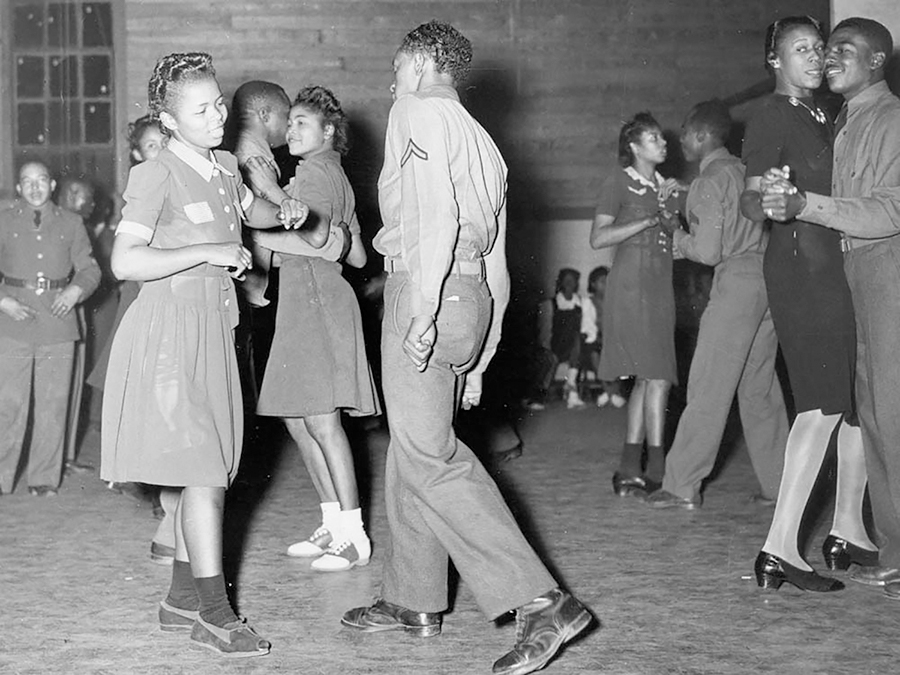

The residents of the Sandhills often saw large gliders overhead being towed two at a time by C-47s. Local farmers had gliders that were off course land in the fields around their farms. Using more conventional means, the paratroopers and families who lived on Camp Mackall often visited the towns of Hamlet, Southern Pines, Pinehurst and Aberdeen, and the townspeople opened their hearts and homes to them. The Moore County towns had established USO centers for soldiers to come and enjoy dances, musicals, plays and a variety of other touring shows.

While many local entertainment centers provided activities of morale and fellowship, there were some locations that provided recreation of another sort altogether. For example, in Richmond County, victory girls (or victory belles) were young ladies who followed the paratroopers in and around camp, especially close to payday. These ladies provided comfort and fellowship for a small fee. It was noted by MacCallum and Stevens that at a house in Richmond County, “three women dated 31 soldiers at $5 a date.”

The Southern Pines USO was located in what is now the Southern Pines Civic Club. The town of Pinehurst was the first to partner with the USO and established an exclusive USO for African-American paratroopers, soldiers and their guests. The integration of the African-American troops into the segregated South did not occur without its challenges. Movie theaters, dining halls, recreation centers, dance halls and living facilities on and off Camp Mackall were segregated. According to MacCallum, “The only facilities not segregated were the Army Post Exchange (PX) and the Officer’s Club.”

After a period of time, African-American paratroopers received access to all services and clubs to include their own non-commissioned officers club. Black and white officers shared the same officers club; however, the enlisted men and non-commissioned officers had their own establishments. The need for the African-American USOs subsequently required the Pinehurst location to move to a larger facility in Southern Pines.

The parachute divisions had a profound impact on the Sandhills social scene and none more so than the historic Negro Paratroop Company, nicknamed the Triple Nickel. The Triple Nickel was the first of its kind. In early 1944, the 555th Parachute Infantry Company was stationed at Camp Mackall with 11 officers and 165 enlisted men. On Nov. 4, 1944, the number of paratroopers swelled to more than 400 black paratroopers and was designated the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. Bradley Biggs, author of The Triple Nickels, Americas First All Black Paratroop Unit, wrote that “the men with families often found Southern Pines more open and welcoming for housing compared to other surrounding towns.”

The Triple Nickel was not the only airborne unit of fame to walk and train in Mackall’s fields and forests. In 1992, Stephen Ambrose wrote the book Band of Brothers, detailing the distinguished history of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. In early 1943, Easy Company, as they were commonly known, conducted intense airborne and infantry training at Camp Mackall in final preparation for combat operations in the European theater. Ambrose’s book, which later gained notoriety as the HBO miniseries of the same name, followed Easy Company from stateside training in Camp Toccoa, Georgia, and Camp Mackall to the parachute assault on Utah Beach on June 6, 1944, and their march across Nazi-occupied Europe till the war’s end in 1945.

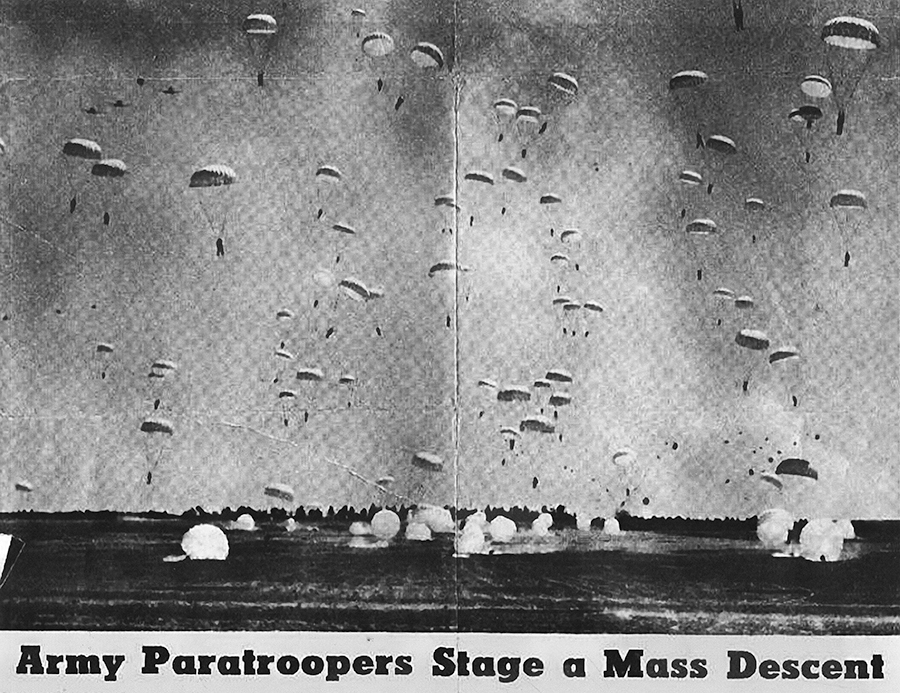

Before any single paratrooper or airborne unit deployed to the European or Pacific theaters, they were required to pass a series of training exercises to ensure combat readiness. At the Department of War, the training maneuvers were designed to determine the operational feasibility of successfully deploying large airborne divisions. The literal fate of the American airborne divisions lay in the maneuvers conducted at Camp Mackall and across the Sandhills region. The most famous maneuver was conducted by the 11th Airborne Division, code named the “Knollwood Maneuver.” The Knollwood Airport, now Moore County Airport, was the target and the place where the airborne division proved its preparedness and worth as a viable force to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander.

On Dec. 6, 1943, the skies above the Sandhills were filled with a massive parachute and glider assault force launched from four airfields to seize the airport. This air armada was a precursor to the planning, maneuver, execution and logistical preparedness that American troops would execute over France a little more than a year later. It lasted six days and, to ensure realism, consisted of 200 C-47 troop and cargo transports that departed from four local airfields, traveled east to the Atlantic Ocean and 200-plus miles back to Knollwood Airport. The C-47 Skytrain, nicknamed the Gooney Bird, delivered 10,282 men by parachute, glider and air landings. During the maneuver, there were more than 880 landings to fly in supplies and reinforcements. The success of the Knollwood Maneuver convinced Eisenhower of the viability of employing airborne forces in division-sized units.

Compared to modern day airborne operations, the safety measures were often regarded as high risk. One soldier recording the Knollwood Maneuver reported, “These glider pilots seem to be a pretty rugged crew as it is the usual thing for them to step out of a wrecked glider, brush off the splinters, and climb into another glider and try again.”

Despite the incredibly rugged nature of these paratroopers and glider pilots, the Knollwood Maneuver cost four paratroopers their lives, and another 49 soldiers were wounded. The men were treated at Camp Mackall’s 1,200-bed hospital. (Despite the hospital’s focus on injuries sustained during airborne operations, it also took care of family needs such as the delivery of 116 babies in its maternity ward.) The Army medical staff was augmented by the American Red Cross and the all-volunteer Gray Ladies Corps. The Gray Ladies hailed from across Moore, Richmond and Scotland Counties. These amazing women were assigned work days by the Red Cross and would help dress wounds, change bandages, talk to patients, play games, read to the men, and generally do whatever was needed to comfort the wounded paratroopers. MacCallum and Stevens, in their book, provide heartwarming testimonies of the lifelong friendships between the women of the Gray Ladies Corps and the paratroopers.

Camp Mackall was also one of many military installations in the United States that housed enemy prisoners of war. There are estimates that the POW count reached as high as 400,000 across America. Including Camp Mackall, there were 18 POW camps in North Carolina alone. Places in the South were selected for their relative isolation from large populations, ease of security, and the warm climate. As many as 300 POWs performed manual labor tasks and agricultural work off the installation in Aberdeen, Pinehurst and West End. MacCallum says, “The peach farmers were required to pay the government 22.5 cents per hour as a contracted labor force.”

As the war came to an end in 1945, the POW camp at Mackall was closed, and the remaining prisoners were transferred to other locations. Camp Mackall began to atrophy. The airborne training center moved back to Fort Bragg, and the unit colors of the 11th, 13th and the 17th Airborne divisions were officially encased.

But Camp Mackall didn’t experience the same fate as many other WWII Army training camps. Today’s Special Forces training pipeline begins at Mackall with its initial Special Forces Assessment and Selection course. SFAS is a three-week, physically and mentally demanding course where soldiers from across the U.S. Army begin the 18-24 month training program. Every Special Forces soldier who earns the right to wear the Green Beret has passed SFAS and received advanced training at Camp Mackall.

Currently Mackall encompasses about 8,000 acres, and within the camp’s boundary, each Special Forces candidate will be provided advanced training in the practical application of speaking different foreign languages, customs and cultures of foreign lands, hand-to-hand combat, weapons training, land navigation, demolitions, and advanced medical training. These specially selected candidates will undergo intense psychological scrutiny in the Special Forces Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape course (SERE). Living off the land, candidates assembled in small groups are hunted down by seasoned Special Forces operatives across Camp Mackall and the Sandhills. The SERE course is regarded as one of the best courses offered by the U.S. military.

Twenty-one counties, including Moore, Scotland and Richmond, play a vital role in the training of every Special Forces soldier. Hundreds of civilian volunteers, police officers and sheriff’s deputies, firefighters, first responders and soldiers from Fort Bragg come together to form the notional country of Pineland. Each candidate must successfully navigate the Robin Sage’s unconventional warfare exercise and assist in the liberation of Pineland. Once successful, each Special Forces soldier has earned the right to wear the Green Beret and be considered one of the world’s premier special operations soldiers.

Robin Sage is a high-risk venture that prepares each candidate for service in the U.S. Army as an elite member of a Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA). Unfortunately, this challenge is not without risk. Sadly, in 2002, Camp Mackall and the Special Forces community suffered a fatal training tragedy between two candidates, a civilian role-player, and a Moore County sheriff’s deputy. One candidate was killed and another was severely wounded. Safeguards to prevent this from happening again have been put into place between the military, law enforcement and our communities.

Access to Camp Mackall is restricted and primarily closed to the public. It’s monitored and patrolled by security forces and often working dogs in training. The ongoing relationship between Mackall and the Sandhills continues to remind us of a time when the two communities came together in the spirit of cooperation to strengthen the morale and effectiveness of America’s elite fighting forces. The trust and mutual respect between the camp and Sandhills citizens has never been more obvious. The Sandhills remains home to Camp Mackall, and together they produce a world-class training environment for elite soldiers — just as originally designed. PS

Retired Lt. Col. Robert P. Curtin is an infantry officer who served multiple tours in the Special Operations Forces. He earned his B.A. in history from Hofstra University and his M.A. in military history from Norwich University. He currently is a social studies teacher and the head wrestling coach at Pinecrest High School.