Dorothy Campbell Hurd — first international star of the women’s game

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

In March 1912, Miss Dorothy Campbell arrived in Pinehurst for a month-long stay at the home of Mr. and Mrs. W.C. Fownes. The 28-year-old Scot was no ordinary houseguest. Acclaimed as the greatest female golfer in the world, she had already won 10 national titles in an astounding run from 1905 to 1912.

It began modestly. To her genuine surprise, in 1903 at age 20, Campbell reached the semifinals of her native country’s most important title, the Scottish Ladies Championship. “I only possessed four clubs at the time, and I had no experience at match play,” she later wrote.

But she was just getting started. In 1905, she reached the semis of the British Ladies Amateur. Two weeks later, her breakthrough victory came in the Scottish Ladies, contested on her home course, North Berwick’s West Links. A throng of 4,000 cheered the hometown lass to a hard-won, 19-hole victory over Molly Graham in the final match. Miss Campbell would repeat as Scottish champion in 1906 and win the title a third time in 1908.

Campbell seemed poised to win her first British Ladies Championship in 1908 when she made the finals at St. Andrews’ Old Course. A massive crowd of 9,000 spectators, including Old Tom Morris, attended. Battling abysmal weather marked by hail and gale force winds, the drenched Campbell heartbreakingly lost the match to Maud Titterton on the 19th hole.

Her disappointment would be assuaged in 1909 when she finally won the British Ladies at Royal Birkdale. After the final match, an overbearing official blocked Campbell’s path to the awards ceremony.

“Are you a golfer?” the official demanded.

Campbell replied, “I don’t think so, but I believe they will want me inside to receive the championship cup!”

The victory resulted in an invitation from the United States Golf Association — itself only 15 years old — to play in the U.S. Women’s Amateur Championship that summer at Philadelphia’s Merion Cricket Club, now Merion Golf Club. Campbell accepted and made her first Atlantic crossing. She adapted quickly to Merion’s parkland layout and sailed through preliminary matches to the final, where she faced a tough challenge. Her opponent, Mrs. Nonna Barlow, was a Merion member. Barlow had Campbell one down after nine holes, but the unflappable Scot took control down the stretch, winning the match 3 and 2, making her the first foreign-born player to win the U.S. title and the first to take the British and U.S. championships in the same year.

She successfully defended her U.S. Women’s Championship in 1910 at Homewood Country Club in Illinois, the first to win back-to-back. Although it was match play, her “medal” score of 78 in the second round was the lowest ever posted by a woman on a course longer than 6,000 yards. Campbell crossed the border into Canada, too, to capture the first of three consecutive Canadian Ladies Championships, and even established a permanent residence in Hamilton, Ontario. She returned to Great Britain in 1911 to compete in the British Ladies at Portrush and won that title for the second time, rebounding from a 3-down deficit to win 3 and 2.

During her 1912 sojourn in Pinehurst with the Fownes family, Campbell set her sights on winning the prestigious United North and South Amateur Championship. She posted the best score in the qualifying round by four shots and was a heavy favorite to add the championship trophy to her burgeoning collection. She reached the final match but was upset by Kate Van Ostrand, who clinched victory when her pitch on the final hole hit the pin.

The Fowneses, Campbell’s Pinehurst hosts, were kindred spirits and golf royalty. W.C. (Bill) Fownes won the 1910 U.S. Amateur. Bill and his father, Henry Fownes, founded and ran Oakmont Country Club, considered America’s most exacting test of championship golf. Bill and his wife, Sarah, saw to it that Campbell’s Pinehurst golf calendar was filled with matches and club competitions.

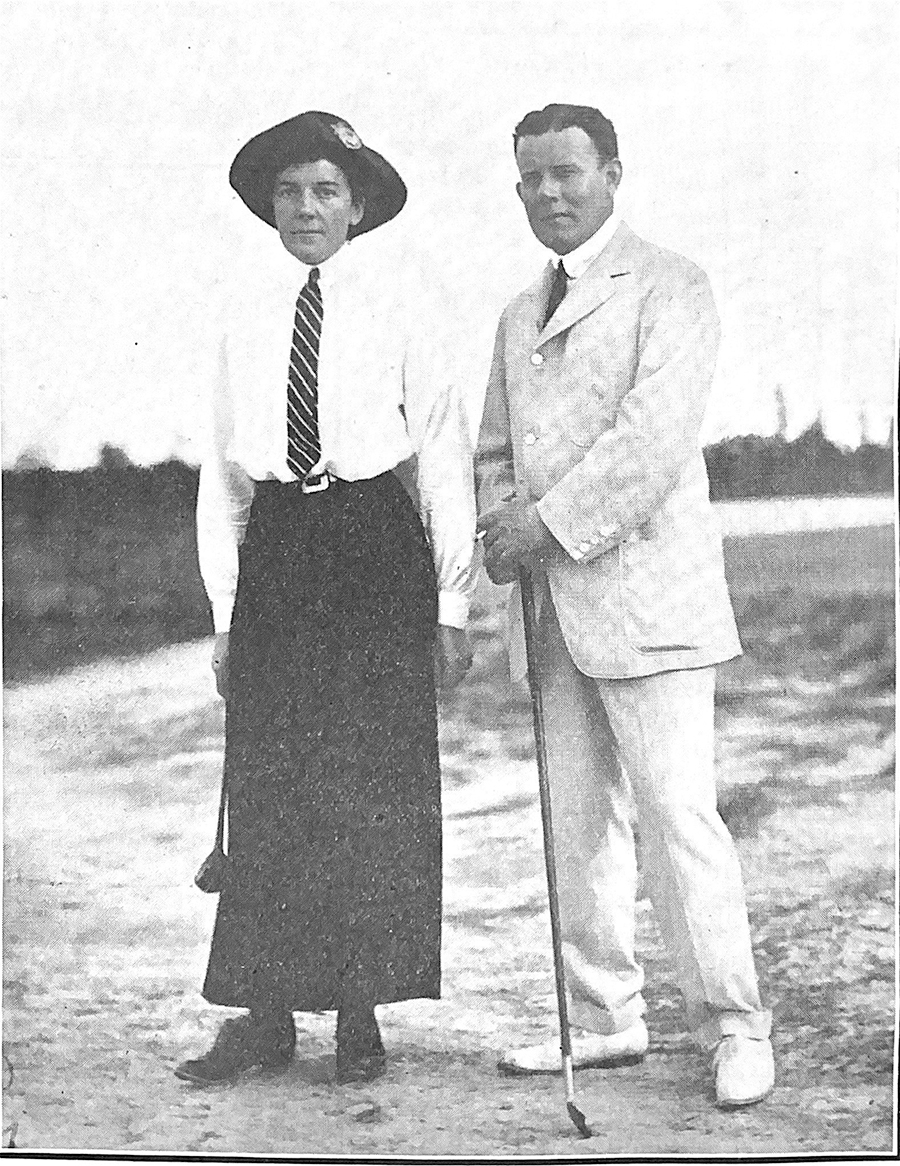

As esteemed members of the “Cottage Colony,” the Fowneses knew everybody in the village’s upper crust. Among their many friends was 35-year-old bachelor Jack Vandevort Hurd, who, like Bill and Henry Fownes, worked in the steel business in Pittsburgh and was a member at Oakmont.

The Fowneses introduced Jack and Dorothy, and a year later, on Feb. 11, 1913, they were married in Hamilton, Ontario, in front of relatives and a few close friends. Following the ceremony, handsome and dapper Jack whisked his bride back across the border to his home in the Steel City. For a champion golfer like Dorothy, with a husband who was a member at Oakmont, Pittsburgh was an ideal place to begin married life. Better yet, she and her husband would be making extended winter visits to Pinehurst. Dorothy would become an American citizen, though forever retaining “her delightful Scotch burr as well as the poise and graciousness of her kind,” according to another champion, Glenna Collett.

Before the end of 1912, Dorothy gave birth to a son, Sigourney Hurd, and golf began to play second fiddle. She supervised the building of a second home in Pinehurst that fronted on the town’s village green. The turreted house at 10 Village Green East, fashioned after an English hunting lodge, was part of a Hurd family compound since Jack’s parents and brother, Nat, owned homes just a niblick shot away. A woman of many talents, Dorothy authored frequent and lengthy instructional articles for Golf Illustrated and Golf Monthly, played the piano and composed songs. She even knitted socks for Allied soldiers during World War I.

While her collection of national championships slowed after her marriage, Hurd still dominated club play in both Pittsburgh and Pinehurst, where she played regularly during the winter as a member of the club’s female golfing society, the Silver Foils. “The Pinehurst courses are proverbial,” she remarked in an article, “for the way they can become dry in a few hours and the next day see play go gaily on.”

During her 10 seasons in Pinehurst, Hurd won the prestigious North and South Women’s championships held in 1918, ’20, and ’21. The number of trophies collected by “Mrs. J.V. Hurd” in other Pinehurst tournaments is incalculable, but the Pinehurst Outlook provided a glimpse of her dominance in winning the St. Valentine’s Day tournament of 1918: “Mrs. Hurd was going (on) in her famous and invincible fashion — not long, but straight and inevitable.”

By 1922 the Hurds’ marriage was unraveling. One telltale sign was the terse paragraph in a March edition of the Outlook reporting that Mrs. J.V. Hurd would not be around to defend the North and South title she had won the previous two years. The couple divorced a year later and Dorothy steered clear of the Hurd family haunts in Pinehurst and Pittsburgh thereafter. Since the couple’s new Pinehurst winter home was completed not long before their separation, it seems unlikely that she spent much time there. She moved her primary residence to Philadelphia and joined the Merion Cricket Club, site of her first U.S. triumph.

With the divorce in the rearview mirror, Hurd dedicated herself to climbing back into golf’s top ranks. Never a long hitter, she’d managed to overcome that deficiency during her championship run with the deadly use of her vaunted goose-necked mashie — an adored weapon that eliminated a previous tendency to shank. She used the club, christened “Thomas,” for run-up shots near the green. It proved especially effective from around 40 yards. In the 1921 North and South, Hurd holed two such shots in the final match to clinch the championship. In emphasizing the importance of the mashie in a Golf Illustrated article, she flashed her dry wit, writing, “Bernard Shaw’s axiom that we should exercise great care in the selection of our parents can be applied with equal force to the choosing of a mashie.”

But several women in the newest wave of fine amateurs — most notably Marion Hollins, tennis star Mary K. Browne, and the powerful Glenna Collett — were driving the ball 50-70 yards past Hurd’s. It was too great an advantage for Dorothy and or “Thomas” to overcome. At 40, could any pro help an aging champion find enough driving distance to enable her to compete against the new wave?

The Merion pro who stepped forward to assist was a man Dorothy Campbell had known in North Berwick: George Sayers. “George was born and brought up in my hometown, and I have known him since he was a boy,” she later recalled. “He told me he could help me change my swing but it would entail inordinate practice.” She had nothing to lose by trying.

Sayers wasn’t the first member of his family to teach golf to Hurd. Thirty years previously, his father, Ben Sayers, taught young Dorothy Campbell back in North Berwick. Dorothy’s home, Inchgarry House, was located hard by the 18th tee of the West Links, and she absorbed the game almost from birth, taking her first swing with a “six-penny” club at 18 months. It became common for golfers mounting the West Links’ 18th tee to encounter the toddler swinging a miniature club outside Inchgarry’s garden gate. In a piece for Golf Illustrated, Hurd wrote “that the fates decreed that I should be fairly impregnated with a golfing atmosphere from the very beginning, even if the family fable that I cut my teeth on the head of a cleek be not true.”

George Sayers switched Hurd’s unorthodox grip (the right thumb under the shaft) to the more conventional Vardon grip. He convinced her to jettison her stiff-wristed sweeping style in favor of a more fluid and athletic move to the ball. A grip change is one of golf’s most daunting projects, and Hurd worked on her new swing and grip for eight months with the sort of single-mindedness that would later mark Ben Hogan’s unceasing practice. She hit balls until the joint on her index finger became a raw wound, but once the changes began taking hold, she unlocked more power. Encouraged, she set her sights on entering the 1924 U.S. Women’s Amateur, held that year at Rhode Island Country Club, the stomping grounds of pre-tournament favorite, Glenna Collett, then in the midst of the greatest year of her Hall of Fame career.

With her best days more than a decade behind her, it was going to be a steep climb for Hurd. The mental aspect of the game was a subject she frequently wrote about in Golf Illustrated. She stressed “absolute concentration on the matter at hand, determination not to let bad luck discourage us and the resolve never to give up hope until the match is over . . . If it can be instilled into a player’s mind he can do a thing, he will generally be able to do it.”

Hurd cautioned against fits of pique with her customary drollness. “A certain theologian whom I have met has more than once told me that he considers the game of golf to be a most dangerous and harmful one, confiding that it’s bad for a man’s character for the same reason that a Presbyterian sergeant in the Boer War objected to bayonet charges — because it makes the men swear so.”

But whether her mental strength would be enough to give Hurd a meaningful chance against the likes of Collett, Browne and Hollins was open for debate. Even with her newfound distance, she would still be hitting second shots from 30 yards or more behind the long knockers.

Having cut her teeth in North Berwick, Hurd was quite comfortable coping with the stiff breezes off Narragansett Bay at the championship site. Her drives were traveling respectable distances, and chips by her ever-reliable mashie were resulting in “gimme” putts. Hurd breezed through to the final, where the smart money had her facing Glenna Collett — once Collett took care of two-sport star Browne in the other semifinal, that is. Collett hadn’t lost a match all year, but Browne scored an upset when her off-line putt at the 19th hole caromed off Collett’s ball and into the cup for victory.

In the final, Hurd was slow getting off the mark and trailed early. Then her putter — nicknamed Stella — caught fire. After 27 holes, Hurd had a 7-up lead. Three holes later, the match was closed out 7 and 6. Hurd’s victory set two U.S. Women’s Amateur records that remain unequaled — oldest winner (41), and most years between titles in the championship (14).

Hurd continued to play well throughout the 1920s and ’30s, winning five Philadelphia district titles. Stella, her deadeye putter, brought her another record in 1926. Playing Augusta Country Club, she used just 19 putts in 18 holes, finishing that amazing round with a chip-in by Thomas on the 18th.

In 1937 Hurd married banker and non-golfer Edward Howe, but the marriage only lasted six years. At age 55, Hurd — then Howe — won the U.S. Women’s Senior Championship. By her own estimation, during her lifetime she won over 700 first prizes.

Tragedy befell Jack Hurd and his second wife, Caroline, when they both perished in an automobile accident in Wilmington, North Carolina, in May 1930. An accident would also end Dorothy’s life.

In 1945, after visiting friends in Beaufort, South Carolina, she was traveling by train to Pleasantville, New York, to visit her son’s wife, Ruth, while he was serving in the Army in the Philippines. As she was changing trains in Yemassee, South Carolina, Dorothy inexplicably lost her footing and fell into the path of an oncoming locomotive. She was 61 at the time of her death.

Dorothy Campbell Hurd Howe — with her mashie Thomas and her putter Stella — was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1978. She wrote that the great shots she played so often with her favorite clubs were “almost second nature to me.” So was winning. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.