A new exhibit welcomes a modernist master

By Jim Moriarty

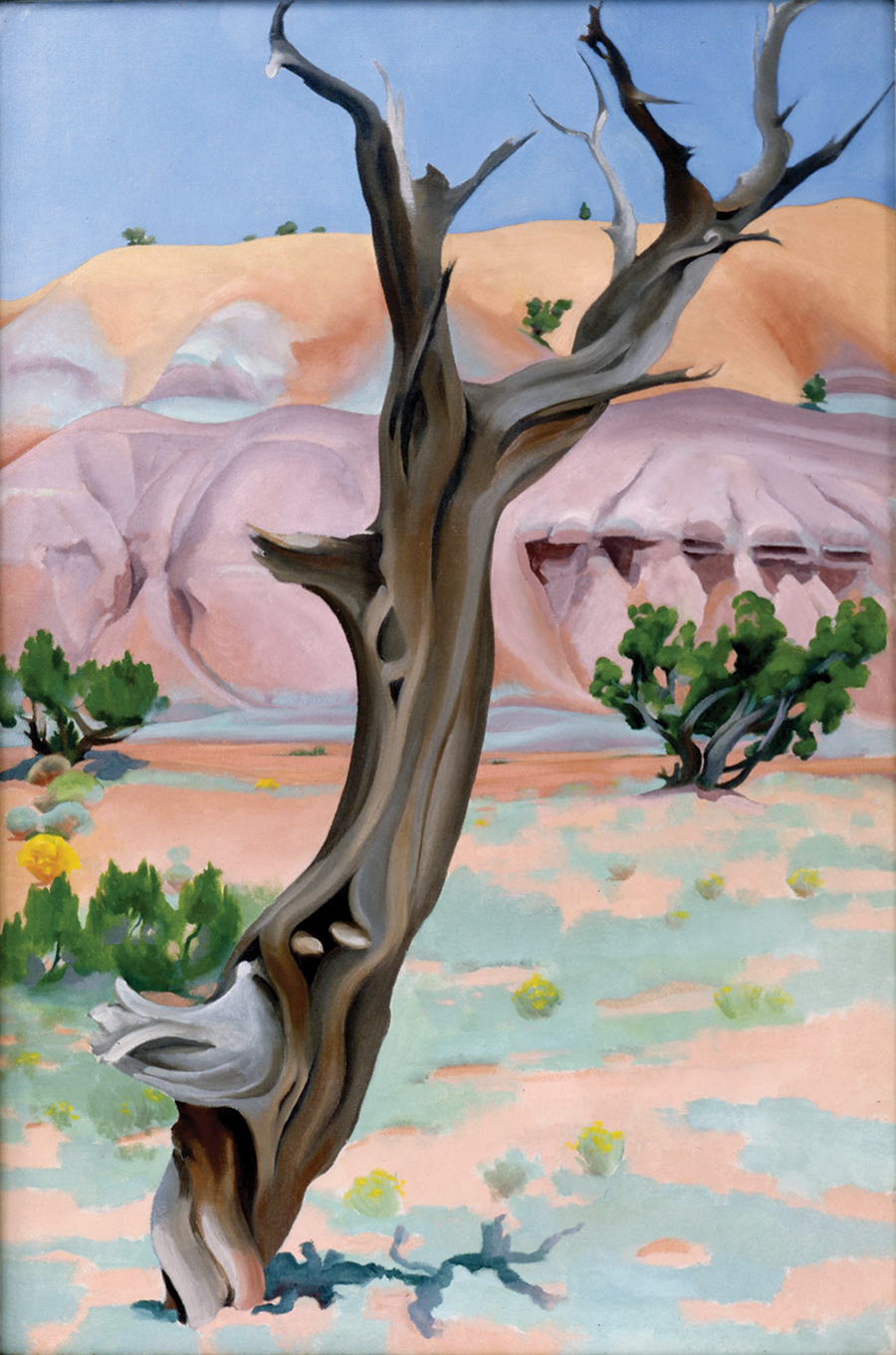

Beginning on the 10th of September the Reynolda House Museum of American Art will be throwing a welcoming party for a particularly interesting work by Georgia O’Keeffe, the renowned 20th century American modernist. The celebration, housed in two rooms, continues until March 6. As if to make the iconic painter of flowers and skulls feel at home in her new home, she’ll be accompanied by old friends, the artists she appeared alongside in famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s series of Manhattan galleries — 291, An Intimate Gallery and An American Place — and the ones she chose to surround herself with during the rest of her life in an exhibition titled “The O’Keeffe Circle: Artist as Gallerist and Collector.”

“We wanted to welcome the painting to Reynolda with a splash,” says Phil Archer, the museum’s deputy director.

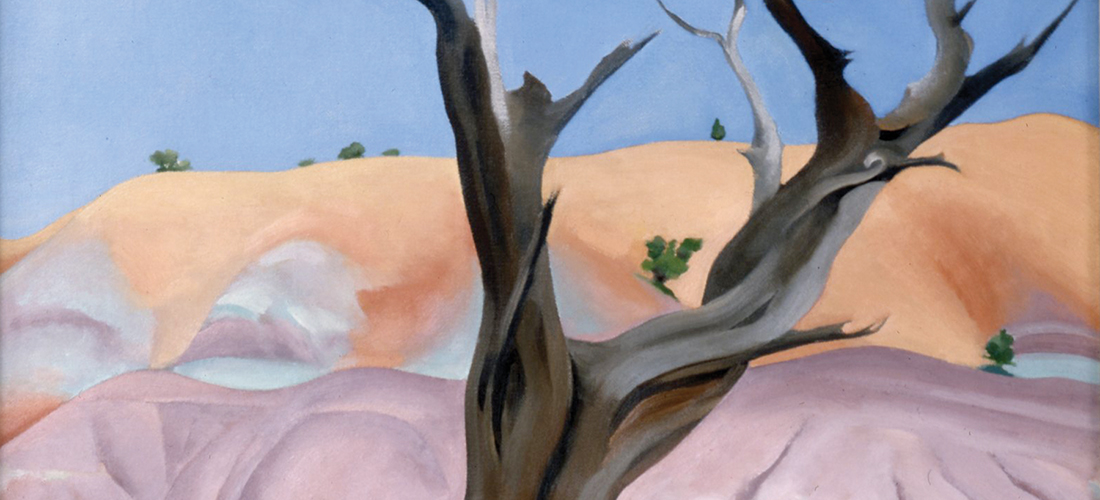

The work, a promised gift from Barbara Babcock Millhouse, the founding president of the museum and its primary donor, is Cedar Tree with Lavender Hills, one of O’Keeffe’s works depicting her beloved New Mexico landscape, first exhibited at An American Place in 1937 and purchased by Millhouse 40 years later. “I have O’Keeffe’s letter to her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, about doing that painting,” says Archer. “She says, ‘I can set it by the window and when I look at the painting and I look out the window, I have actually captured the way my world looks.’”

The painting will appear alongside another O’Keeffe work already in the museum’s collection, Pond in the Woods, Lake George. “It’s great for Reynolda because we’ll now have a painting from each of O’Keeffe’s main loci of inspiration,” says Archer.

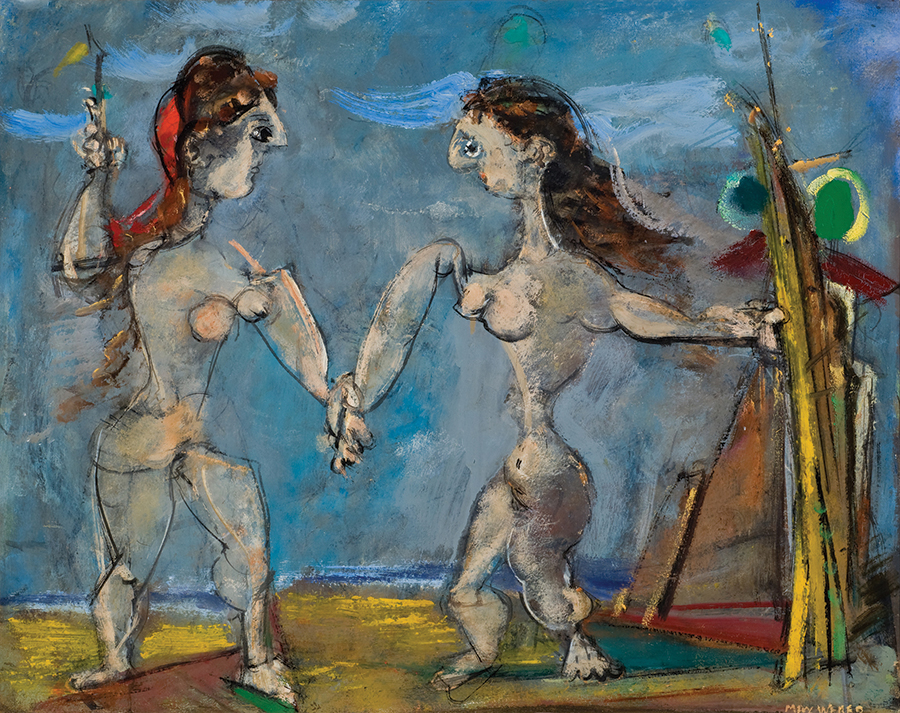

Joining O’Keeffe will be a brace of her contemporaries, including John Marin, Arthur Dove, Alfred Maurer, Marsden Hartley, Max Weber, Abraham Walkowitz and Charles Demuth, a flock of artists more often described as the Stieglitz Circle but who are recognized here for their effect on, friendships with and passion for O’Keeffe. “Stieglitz was always declaiming who was the next artist and why people should appreciate them,” says Archer. “The exhibit is kind of a pocket-sized pantheon of the great, early moderns. They’ve all drunk from the well of French modernism. They’ve all read Kandinsky about the spiritual potential of art and abstraction. There’s this kind of reckoning. What will Americans make of the new artistic world in the teens and twenties? That’s what Stieglitz was calling for — what will modernism mean for us?” And, in Stieglitz’s mind, the abstract movement went hand-in-glove with the elevation of photography as an art form all its own.

Demuth was not originally in the Stieglitz stable, but in 1921, when he became “one of us,” as O’Keeffe described him, she enjoyed his company immensely. A friend of the poet William Carlos Williams, he was elegant and urbane, a gay artist with a lively sense of humor but frail health. Though he turned to oils later in his life, he was best known as a lively watercolorist. As a mark of his friendship with O’Keeffe, when he passed away in 1935, he left all his oil paintings to her.

Marin was introduced to Stieglitz by his friend and fellow photographer Edward Steichen and became enough of a commercial success to buy his own small island in Maine, where he lived during the summer. O’Keeffe admired his work, including a blue crayon abstract drawing. In Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life, Roxana Robinson writes, “Its intimate scale and its clear aesthetic independence made it suddenly accessible to O’Keeffe: conceptually, this was very close to her own work. It occurred to her that if Marin could make a living selling this eccentric expression of a private aesthetic vision, then she might be able to do the same.” He was close enough to both Stieglitz and O’Keeffe to be a witness at their 1924 wedding.

O’Keeffe’s first exposure to Dove at 291 was his painting Leaf Forms. After returning from Europe in 1909, Dove spent weeks camping alone in the woods. His abstract paintings “found a strong echo in Georgia’s developing aesthetic philosophy,” writes Robinson. “Dove’s work validated her own inclinations . . . she sensed the deep affinity between them.”

Dove was equally enamored. “That girl is doing without effort what all we moderns have been trying to do,” he said to the poet Jean Toomer.

Walkowitz worked so closely with Stieglitz at 291 that in 1912 and again in 1914 Stieglitz exhibited the work of the children Walkowitz was teaching in a Lower East Side settlement house. In this exhibit, Walkowitz is represented by one of his 5000-plus drawings of Isadora Duncan. “She had no laws. She did not dance according to the rules. She created,” Walkowitz said — words that he could have applied to O’Keeffe just as readily.

Paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne, and Auguste Rodin’s drawings were first shown in America at 291. Marin and Maurer appeared on their heels. Maurer, like O’Keeffe, had studied with William Merritt Chase. Maurer’s father created Currier and Ives lithographs and never approved of his son’s modernist leanings. Shortly after his father passed away at the age of 100, Maurer committed suicide. The mercurial Weber was responsible for Henri Rousseau’s first U.S. exhibit, and he helped introduce cubism to America, a thankless task in 1911. According to the art historian Milton Brown, he was rewarded with “one of the most merciless critical whippings that any artist has received in America.” And it was an exhibition of Hartley’s work that first brought O’Keeffe to the 291 gallery where she met Stieglitz. Soon they would be lovers.

Though the works linked to O’Keeffe as a collector, or perhaps appreciator, in the exhibit are not the precise pieces she held in her collection, they are representative of those that were and of the relationships she enjoyed. Among the latter is her abiding friendship with Ansel Adams, who is represented by one of his prints of Yosemite Valley, a place O’Keeffe and Adams visited together. In a letter to Stieglitz, Adams wrote, “O’Keeffe is supremely happy and painting, as usual, supremely swell things. When she goes out riding with a blue shirt, black vest and black hat, she scampers around against the thunder clouds — I tell you, it’s something.”

The exhibit includes a photograph of Adams and O’Keeffe taken by Adams’ assistant, Alan Ross. “Ansel Adams was the first professional photographer to capture her on camera and then in 1981, close to both of their deaths, she went back to Carmel, California, and, as she’s setting up, she’s sort of smiling, his assistant took a quick snapshot,” says Archer.

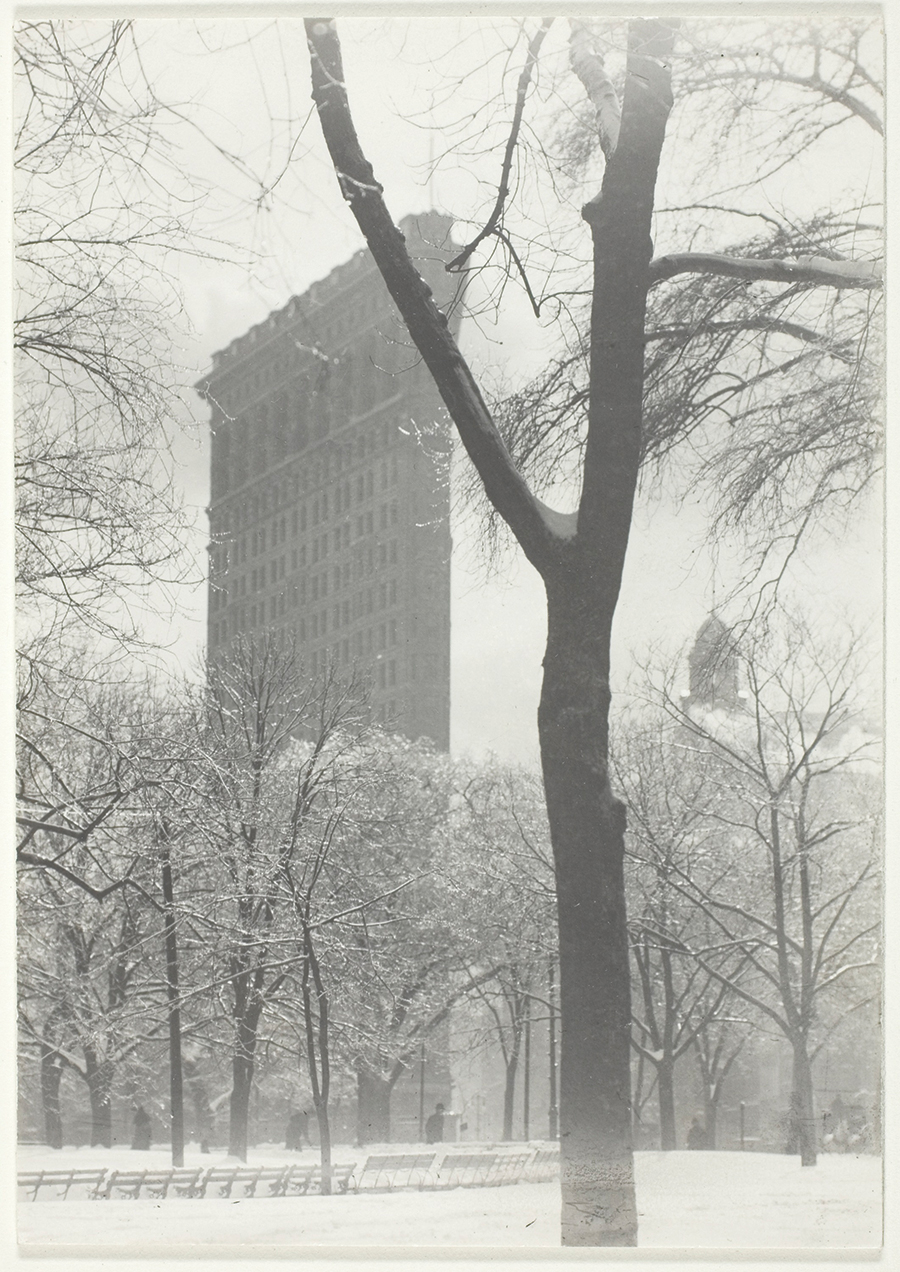

Also included in this section of the exhibit is an Akari paper lantern by Isamu Noguchi similar to the one O’Keeffe alternately hung over her dining room table or her bed in her house in Abiquiu, New Mexico. There is a mobile by Alexander Calder — who designed the OK pin O’Keeffe wears in countless photos — that is analogous to the one O’Keeffe hung in her New Mexico home. A triptych of snow scenes done in the 1850s by Utagawa Hiroshige is also included as an homage to a similar threesome of Hiroshige woodblock prints from the same period that lived on the wall in O’Keeffe’s New Mexico home and are now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And, naturally, there is a Stieglitz print, one of his most famous, also a snow scene. “I suddenly saw the Flat-Iron Building as I had never seen it before,” Stieglitz said. “It looked, from where I stood, as if it were moving toward me like the bow of a monster ocean steamer, a picture of the new America which was in the making.”

This intimate exhibition does not pretend to be, nor was it intended to be, an O’Keeffe retrospective. It does not deal with her complicated relationship with Stieglitz — who never ceased to promote O’Keeffe’s work — their lengthy affair before his divorce, their subsequent marriage and, later, his affair with his gallery director, Dorothy Norman. It doesn’t delve into her mental and physical breakdowns in the ’30s nor does it touch on the sexuality, male and female, that is often ascribed to O’Keeffe’s work and which she steadfastly refused to acknowledge.

Like Stieglitz’s photo of the Flat Iron Building, O’Keeffe saw grandeur in her subjects. “She wanted the small things in nature that she loved to be just as impressive as the new trains and new planes,” says Archer, “to stop you in your tracks like you were looking at a skyscraper.”

The tightly knit exhibit, like the Ross photo, is a snapshot of the artist. “I hope people will leave with a fuller image of O’Keeffe’s engagement with the art of her time,” says Archer. “She developed a persona — helped by Stieglitz — of the remote, contemplative, detached doyenne of the desert. But she was keenly interested in her contemporaries’ work and unstinting with both praise and criticism.” PS

Jim Moriarty is the Editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.