For Carthage homesteaders Ken Riggsbee and Carolyne Davidson, environmentalism and sustainability set the standard

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

Huff and puff as he may, the Big Bad Wolf can’t blow down Ken Riggsbee and Carolyne Davidson’s house. Because it isn’t made of straw, or sticks, or even bricks. The exterior walls are massive slabs of poured-to-order concrete trucked from a factory and lifted into place by a crane, fastened together with steel. The above-ground basement is partially excavated, cave-like, into a slope. The concrete, recycled from coal ash and an insulation itself, is further insulated with foam.

“Completely air-tight,” Ken states proudly.

Premium efficiency windows come from Italy. A geothermal system draws heating/cooling from the ground; while expensive up front, it slashes energy costs. The house faces south for maximum solar gain and, in the summer, is shielded from direct sunlight by an overhang. Every detail of this dwelling illustrates durability and, most importantly, green standards.

Furnishings lean toward practical, indigenous rather than eclectic, heirloom, Victorian or post-modern. Carolyne’s kitchen channels Mother Earth, not Architectural Digest.

Both upper and lower floors have accessibility features. “Aging in place was my design,” Ken says.

Obviously, there’s a backstory.

“I’m a city girl.” Carolyne grew up in a suburb of Edinburgh although her Scottish burr has almost disappeared. “Our house was stone, made to last.” She has a Ph.D. in strategic studies in history from Yale University, and now teaches at National Defense University at Fort Bragg. Ken grew up in what he calls a traditional two-story brick Southern Baptist house, in Carrboro. He worked construction (specialty: swimming pools) alongside his father, joining the Army after high school and eventually serving with Special Forces. Their first date, in D.C., happened on the day in 2003 when Ken’s offer on 47 acres in Carthage adjoining Farm Life School was accepted. With the land came a dilapidated house, formerly a hospital and then infirmary, when Farm Life had boarding students. The Riggsbees still find small tiles in the ground, probably broken off the surgery floor.

Carolyne knew Southern Pines from Army friends; her parents had golfed there. Ken, also conversant in civil engineering, knew the area from being stationed at Fort Bragg. They married, visited Carthage frequently, finally relocating permanently in 2009 into the falling-apart infirmary.

“I didn’t even have an American driver’s license,” Carolyne recalls. “I learned to drive on the right side of the road, on a tractor.”

Attempts to save the house failed. Newly pregnant Carolyne became a drywall expert, to no avail. Besides, Ken had a plan: “I bought it for the land. The house we built was the vision I had — wife, children, animals — my American dream come to fruition.”

They broke ground on Sept. 8, 2015, and completed the 4,600-square-foot house in 16 months.

Ken, who is a font — no, a geyser — of construction information, most hyper-technical, all impressive, found a green-leaning architect and subcontractors capable of implementing his vision. He and Carolyne set forth goals and conceived an unusual, elongated floor plan. One wing immediately left of the front door includes the master bedroom, bath and dressing rooms. A small hallway opens out into the two-story great room divided by use, not barriers, into a common space (with TV), eating area and kitchen. Light pours in from clerestory windows.

“I like elevation and light,” Carolyne says.

Ken prefers to be snug, close to the ground. But he does love the acoustics of a soaring space.

A loft with doors at each end overlooks the living room. Behind the doors — storage. In the opposite wing are bedrooms for the Riggsbee’s two daughters, Isla and Iona, named for Scottish islands. In the center, a kitchen with 5-star energy rated Bosch appliances, designed in Germany, made in New Bern, N.C., and cherry cabinets with paneled doors mounted inside out for an Arts and Crafts-style appearance. Black granite for the countertop was quarried locally. On it sits dinner in a box from organic Green Chef.

A covered gallery runs the entire length of the house, then wraps around the sides. Ken’s projection for this outdoor living space: “In 10 years, when Carolyne and I go away for a long weekend, we expect there will be 125 high-schoolers bouncing around on that deck.”

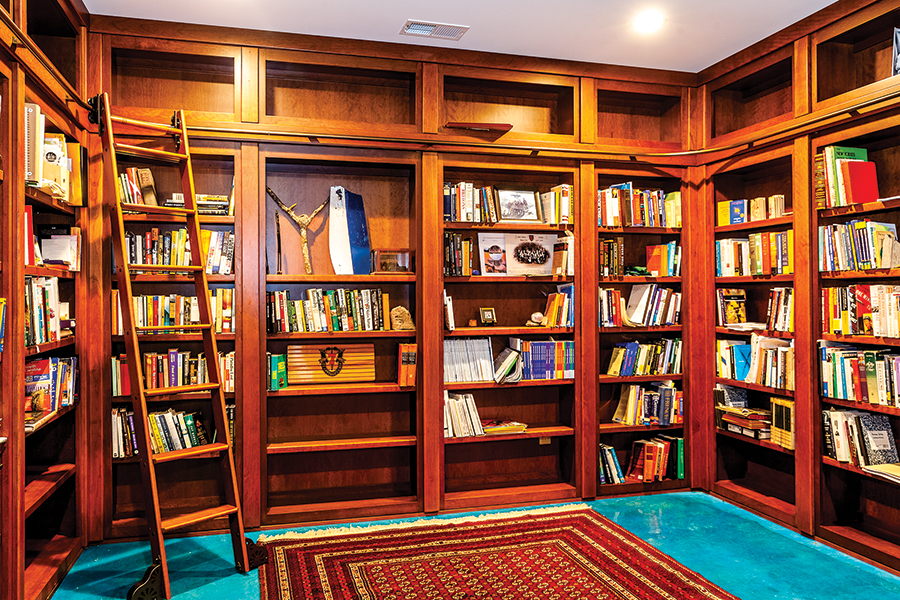

The walk-out basement stretches 32 feet encompassing a family room, offices for Ken and Carolyne, a bathroom and children’s toy-and-book enclave large enough to accommodate a kindergarten as well as a suite for Carolyne’s parents, who visit from Scotland twice a year.

The entire two-story frontage overlooks a pond teeming with fish that jump to the surface at feeding time. Ken keeps honeybees to address pollination and sustainability issues. Goats, chickens, ducks and four cats roam free, attended by the city girl whose only pet growing up was a hamster.

Ken and Carolyne admit an affinity for Frank Lloyd Wright. However, a single word best describes the interior of this intensely personal home: wood. Dark wood floors and window frames, doors and built-ins, tables and cabinets. Ken warms to the history of each board. Beams across the 19-foot ceiling are decorative, not structural, he admits, “but they are 100 years old.” Lumber for plain baseboards and trim was harvested from pine growing within the footprint. The dining room tabletop comes from a black walnut tree that died on the property; its edge, rather than squared off, retains the natural curve.

“We don’t use table mats,” Carolyne explains. “The tabletop is a living thing we share.”

Walking room to room, Ken identifies the source of other woods their cabinetmaker turned into furniture. Ken built the girls’ bunk bed himself.

With the exception of lavender in Isla’s room, all walls (with rounded corners, for safety) are a creamy French vanilla. Wall décor is a work in progress, with art waiting to be framed. Until then, the views are enough, Carolyne says. Ken has hung some military mementoes and Carolyne, a stunning portrait of a Tibetan friend. Floors upstairs and down are mostly bare, with an occasional carpet Ken brought back from deployments in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

This home-building saga was not without risks and inconveniences. Ken had to fight for his specifications, based on the German “passivehaus” model. The Riggsbees are within reach of cable TV but the high-speed internet isn’t great, Carolyne discovered. “We moved here before there was the Food Lion (on N.C. 22). It took a while getting used to not walking to a restaurant.” She doesn’t feel isolated, however, since both she and Ken drive to work at Fort Bragg every day.

They seem satisfied and proud of their accomplishment but not complacent. The unfixable infirmary has been razed; Ken hopes to build a workshop on its site. An old swimming pool that came with the property needs work before they can fill it, hopefully in time for those high-schoolers partying on the gallery.

Not to worry. There’s plenty of time since, as Ken states, “I plan to live here for 150 years.” PS