The twists and turns in the life of the man who gunned down the chief of police

By Bill Case

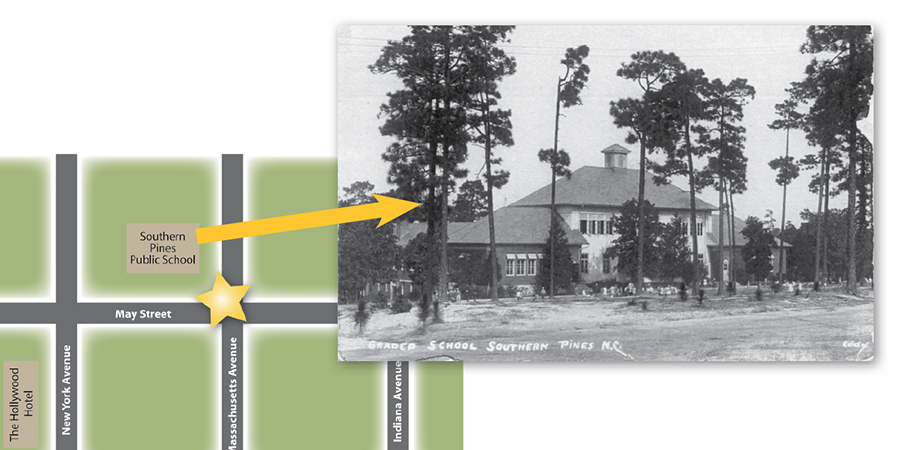

Southern Pines Police Chief Joseph Kelly made a point of stationing himself at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and May Street as grade school let out on Wednesday, March 20, 1929. His presence was little more than a casual reminder about the new stop signs installed for the cross traffic going up and down Massachusetts’ steep slope. The first day of spring was tomorrow, but Kelly would barely live to see it.

Parking his cruiser near the school wasn’t exactly high-intensity police work, though May Street had seen some notable exceptions. It doubled as part of what later became State Highway 1, and movers of bootleg liquor would inevitably pass through town. On one occasion a speeding motorist failed to heed the chief’s command to stop. Kelly leaped on the sedan’s running board as the driver swung a hammer at him. Eventually subdued, a search of the stranger’s automobile revealed a cache of contraband hooch. It was reason enough to carefully eye the traffic moving through the intersection on a crisp, sunny afternoon.

It’s unknown why 27-year-old Granville Deitz, a native of mountainous Greenbrier County, West Virginia, happened to be in Southern Pines, driving east on Massachusetts. He later said he was on his way home from Florida. Already wanted on the charge of burglarizing a U.S. post office and for holdups of several small town stores and gas stations, he was a man with something to hide.

Deitz blew through the recently installed stop sign, and Kelly motioned for him to pull over. He complied, parking on Massachusetts just west of the intersection. As Kelly approached the Chevy, something must have aroused his suspicion. Whether it was the car’s South Carolina license plate, the young man’s demeanor or the suspicious tools in the back seat, the chief guessed the slim, dark youth was bootlegging whiskey. At Kelly’s command, Deitz stepped out of the car. The chief bent over to commence his search. According to Deitz, he became angry when Kelly began reading loose mail left in the car. Blows were exchanged and Kelly reached for his gun. Claiming “it was either me or him,” Deitz fired four shots from his own revolver at a distance of three or four feet before Kelly could draw his weapon. A witness, local contractor E.V. Perkinson, gave a far more damning version of events. He testified that as soon as Kelly turned his back and leaned over, Deitz whipped out his gun and fired away.

Kelly was in a bad way, but somehow managed to stagger to his patrol car and drive one block to the residence of Dr. William C. Mudgett, where he collapsed to the ground. Dr. Mudgett made Kelly as comfortable as possible and summoned an ambulance to transport the gravely wounded chief to Highsmith Hospital in Fayetteville, an agonizingly long ride. The Sandhills did not yet have a hospital, though the cornerstone for the new Moore County Hospital had been laid the day before Deitz riddled Kelly’s body with bullets. The 51-year-old police chief died at 2 a.m. the following morning. He was survived by his wife and one child.

Meanwhile, Granville Deitz was in full flight. Abandoning his car, he sprinted south down May to Indiana Avenue, where he jumped into an unattended auto and tried to start it. The car’s owner, Homer Eckert, ran from his house to confront Deitz, who quickly concocted a story, explaining that “a man had been shot” and he urgently needed to rush to the Carolina Hotel in Pinehurst to summon a physician who was staying there. Deceived by Deitz, Eckert offered to drive the killer to the hotel. When they arrived at the Carolina, Deitz asked Eckert to wait for him while he located the phantom doc. The gunman slipped out the hotel’s back door and hijacked Mrs. L.L. Leonard’s cream-colored Buick from the nearby Pinehurst Garage (now Clark Chevrolet Cadillac). Soon he was steaming west on dusty Route 211 toward Candor.

Not knowing where the unidentified suspect was headed, Moore County Sheriff C.J. McDonald, Kelly’s Deputy Chief Ben Beasley and Southern Pines Mayor Paul Barnum quickly organized a posse. Fort Bragg dispatched airplanes to search the back roads for the stolen Buick. Meanwhile Deitz continued west through Candor. Fifteen miles beyond Monroe, he jettisoned Mrs. Leonard’s Buick, fled into the woods, and as The Pilot later phrased it, “vanished into thin air.” Not only had the police chief been murdered in broad daylight, the killer had made his escape from Southern Pines with relative ease. It seemed Granville Deitz was gone for good.

Beasley, who took over as chief in the aftermath of Kelly’s death, expressed confidence that the killer would be rapidly brought to justice, but the evidence he obtained searching Deitz’s Chevy wasn’t much to go on. Several different license plates and hotel keys were found along with some newspaper clippings recounting his own criminal exploits. It was as if Granville Deitz was the spiritual offspring of Bonnie and Clyde reading his own press notices. The most helpful clue came from the letter Kelly may have been reading just prior to the gunfire. It was from Mrs. E.W. Boso of Summersville, West Virginia (near where Deitz resided), addressed to J.L. Boso in Winston-Salem, and signed, “Mother.”

The new chief called the police in Summersville and learned that Boso had been recently apprehended for committing crimes while working in tandem with Deitz, whereabouts unknown. Perhaps it was Kelly’s discovery of the letter that had been the motive for Deitz’s violent actions. By April 18, The Pilot announced Deitz as the prime suspect in the Kelly killing. The fugitive’s high school picture accompanied the article.

Beasley’s investigation took him to West Virginia, where he learned Deitz had a steady girlfriend in Greenbrier County — Miss Maysel Gibson. While the details are a bit murky, it appears the young lady agreed to cooperate with the police rather than run the risk of aiding and abetting her boyfriend. When it turned out Deitz had fled north to Maine, the authorities asked Gibson to wire him money. A sting was set up in Millinocket, Maine, where two police officers waited for Deitz at the local telegraph office and seized him. He resisted, but to no avail. Beasley’s detective work had resulted in Deitz’s capture nearly seven weeks after the shooting. It was with grim satisfaction that on May 8, Beasley wired the new Southern Pines Mayor A.G. Stutz announcing that he had “Arrived Bangor, Me., 11:30 AM. Stop. Left 1 PM with Granville A. Deitz. Stop. Identification certain. Stop.”

Extradited to North Carolina, Deitz was charged with first degree murder. The death penalty loomed. The Pilot’s editor, Nelson Hyde, rejoiced. “The man who in brutal cold blood shoots down an officer or citizen is not allowed to go away without the hail of vengeance trailing closely behind him,” he wrote.

District Judge Thomas J. Shaw set the trial date in Carthage for May 24, 1929 — a mere 20 days after Deitz’s capture. Deitz had precious little time to find counsel, let alone locate witnesses and prepare for a jury trial in which his life was at stake. His mother, Betty Nutter Deitz, rushed in and took charge. She assisted in retaining a defense team, including Fayetteville’s celebrated criminal lawyer Col. C.W. Ostenton. The dusty long-forgotten case docket in the bowels of the Moore County Courthouse show that the defense argued Kelly had no right to arrest Deitz for a stop sign violation, and that there was no evidence of any violation of any ordinance that would have allowed Kelly to detain Deitz. The defense also argued that Granville Deitz “had a right to resist and use all the force which in the judgment of the jury was necessary to free himself.” His argument was akin to a “stand your ground” defense.

The best thing going for the defense, however, was the steadfast support exhibited by Deitz’s family and friends. His mother was said to have “excited much sympathy for her son.” Several locals actually showered Deitz with gifts of books and flowers during his stint in the county jail. The eldest of nine children, Deitz had been the product of a good family. His father, Watson, kept food on the table by teaching, farming, surveying and running the local post office. Deitz’s mother taught school and managed the farm. Dennis Deitz, who idolized his older brother, noted that Granville, though small in stature, reveled in competition in anything, from football to formal debate. “His rebuttals were unmatched,” Dennis Deitz later wrote. “When an opponent made a point and gave his sources and authorities, he would reply by quoting an article from a noted expert, written three years before in maybe the Saturday Evening Post. The judges would be amazed. This unbelievable recall came from Granville’s imagination. The judges or opponents never suspected the truth.” Deitz’s talent with a gun was equally legendary. According to his brother, Deitz could shoot “flying hickory nuts with his pistol from 30 feet away,” and could fire and reload with blinding speed. It proved a lethal skill set.

The lawyers’ technical arguments and family aid weren’t enough for Deitz to overcome the evidence against him, however. The clincher for the prosecution occurred when J.L. Boso’s confession implicating Deitz in their series of gas station holdups was read to the jury. When the Saturday night verdict of guilty to the reduced charge of second-degree murder was read before a packed courtroom, Granville Deitz displayed no visible emotion. He kissed his mother goodbye after being sentenced by Judge Shaw to 25 to 30 years at hard labor in the state penitentiary.

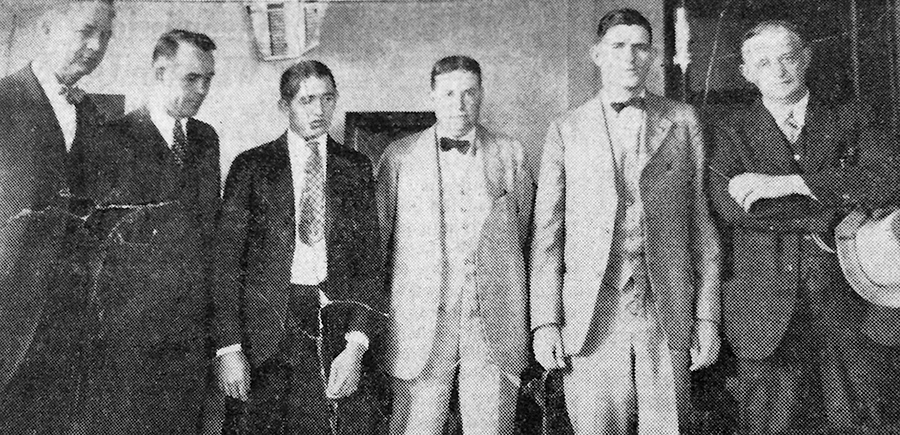

Quite pleased to appear with their somber-looking trophy, the dignitaries who attended the trial posed in a photograph with the uncuffed Deitz. In a public statement after his adverse verdict, Deitz expressed his gratitude for the gifts of well-wishers and appreciation for the manner in which he and his family had been treated. A scathing editorial in the Sanford Herald wondered, “if these same people sent flowers and books to the wife who was made a widow and the children (sic) who lost a father while doing his duty as a sworn officer of the law, at the hands of this bloodthirsty criminal who it is believed took (Kelly’s) life to conceal crimes he had already committed.” In fact, the Southern Pines community had taken up a collection for the benefit of Kelly’s wife and child in addition to raising $2,500 in reward money, $250 of which went to Chief Beasley.

The town collectively breathed a sigh of relief that Kelly’s killer had been brought to justice and would be languishing in state prison for what could be the rest of his life. But Deitz’s escapades were far from over. On Dec. 12, less than seven months after his conviction, Deitz escaped the prison farm by automobile. According to The Pilot, two young women in a car with West Virginia plates had been seen in the area of the prison prior to the escape. Author James Boyd was moved to sarcastic whimsy in his column “Gallberries” carried in The Pilot:

—§—

Granville Deitz by leaving no

address has put some of our people at

a loss.

—§—

They don’t know where to send

him flowers now.

—§—

It was pretty tough to put him

on that farm.

—§—

He ought to have been sentenced

to a greenhouse.

—§—

Just because a man is a murderer

is no sign that he likes life on a farm.

Deitz made his way back home and promptly married Maysel Gibson. Later he remarked, “We knew when we were married that the possibility of eventual capture faced us. But we felt that life without each other would be an empty affair.” Realizing that Greenbrier County would be the first place the North Carolina authorities would look for him, Deitz and his new bride hightailed it north across the Ohio River to Gallia County, Ohio, where he assumed a new name — William Nutter.

Meanwhile, law enforcement and the press in Southern Pines obsessed over Deitz’s whereabouts. Labeled as something of a master criminal, he was the prime suspect in every unsolved crime. Every longleaf pine seemed to have a Granville Deitz lurking behind it. A lone gunman who engaged in a shootout in Heywood County was rumored to be the escaped fugitive. The holdup of a gas station in Vass was thought to be Granville’s work until the suspect was caught in Cheraw, South Carolina, and it was not Deitz after all.

In the July 4, 1930 “Grains of Sand” feature in The Pilot, the question was asked, “Wonder where Granville Deitz is spending the summer vacation?” Actually, Deitz, aka William Nutter, was faring quite well. After having worked in farming and carpentry in Gallia County, he moved 30 miles farther north to Jackson, Ohio, where he caught on with the local Pure Oil distributor making deliveries and collecting bills. Instead of robbing service stations, Deitz was receiving voluntary payments from them. Then, when his boss became ill, “Nutter” was entrusted with running the entire business. He applied himself to the task and kept the operation humming. Maysel taught school and gave birth to Elizabeth in 1931. The William Nutter family had achieved a high degree of respect in Jackson. Life was as good as it could be for a couple hiding from the law.

But, public fascination with crime and criminals led to exposure. In 1935, a popular detective magazine mentioned Granville Deitz in its “most wanted” section and included his photo. When someone in Jackson saw the picture of the man known as William Nutter, the jig was up. Surely, a shiver ran up Deitz’s spine when police came to arrest him. Taken to the county jail, he awaited extradition to North Carolina once again. But local citizens didn’t turn away from the man they knew as William Nutter. Their outpouring of support led to a petition with 1,000 signatures beseeching Ohio’s governor not to allow his extradition. Deitz later said that the back door to the jail was intentionally left unlocked, but he was done running. Declining his chance to escape, Deitz waived extradition.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Deitz explained. “I didn’t want to come back and serve the long term I’ve got left because it was taking me away from my wife and baby and away from the life in which I was making good . . . There’ll probably be nights when I’ll just lie down and curse myself for not going out that back door in Ohio. But I’ll stop at cursing. I won’t go out any more back doors.”

Chief Beasley never witnessed the return of the fugitive he had labored to apprehend. Like his predecessor, he died in the line of duty, in October 1931, gunned down by a prisoner he was escorting to headquarters. Though reconciled to returning to prison, Deitz wanted out as soon as possible. The family retained Sanford’s J.C. Pittman in 1937. Sheriff McDonald declined to sign a parole petition prepared by Pittman. “Even if Deitz is a ‘changed man,’ I fear it would set a bad precedent for the other prisoners to extend clemency so soon to one who had been an escapee,” said McDonald. With Deitz stuck for the time being, his wife spent her summers in Raleigh taking teaching classes at North Carolina State and visiting her husband.

Lauded as a “model prisoner,” and with the acquiescence of his trial jury and Kelly’s family, Deitz was paroled in October 1940 after only five years of incarceration on the condition that he stay out of North Carolina. “I’m going to West Virginia as fast as I can get there to see my wife and child,” he said. Deitz planned to go back to his old job, which was waiting for him back in Jackson. “I want to go back to being a good citizen.”

We don’t know why, but Deitz decided not to return to Jackson, going instead to his home state of West Virginia, where evidence suggests he became an insurance agent for Mutual of Omaha. A natural salesman, Deitz made a success of his new career and rose to district manager. His entertaining storytelling led to speaking gigs at company sales conventions and local civic clubs, where Deitz would regale the crowd with mountain tales, some true, some folklore. He took the time to write his stories down.

Granville Deitz died in 1966 at age 64 while still on the job with Mutual of Omaha. In 1981, Deitz’s family arranged for the publication of his tales of the hills in a book titled Mountain Memories. A rousing success, it was reprinted three times. Brother Dennis Deitz subsequently published his own popular writings of Mountain Memories one of which discussed the exploits of his revered older brother. Absent in both publications was any mention of an encounter with the law in Southern Pines.

The crime and the killer may forever go unforgiven. Or, perhaps, a life can be redeemed, in part. Either way, Granville Deitz, the omnipresent menace, was a menace no more. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.