A Chin Scratcher

Stuck in the era of the presidential close shave

By Scott Sheffield

Whither hast thou gone, presidential whiskers? No American president has sported facial hair of any kind since Howard Taft left office in 1913, except for the mustache and goatee cultivated for a short time by Harry Truman after the 1948 election. Before Taft, no American president had gone without it since James Buchanan ceded the office to Abraham Lincoln in 1861, except Abe’s successor, Andrew Johnson, and William McKinley. During that era, the diversity of presidential facial growth ran the gamut of possibilities. Long sideburns, mustaches, mustaches with muttonchops, full beards with mustaches and without.

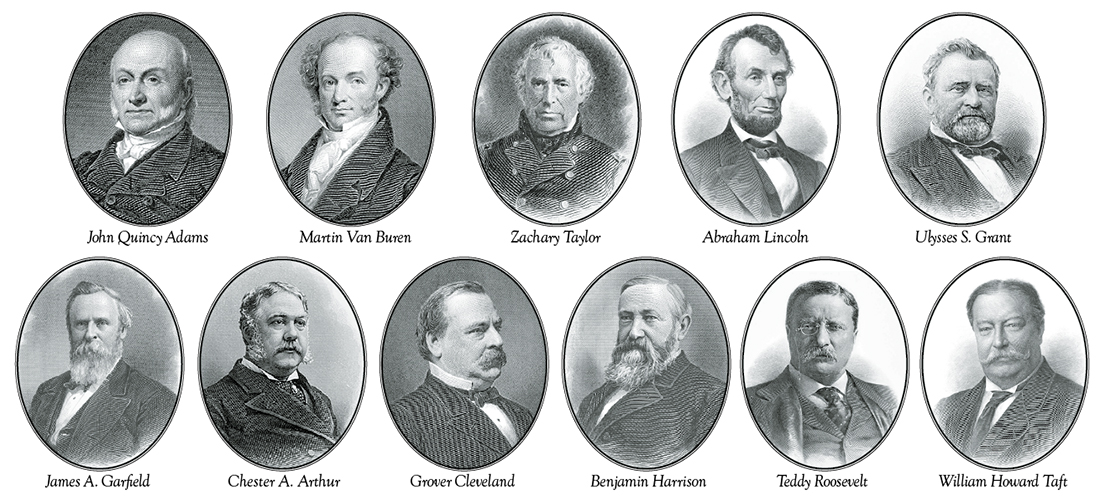

John Quincy Adams (1825–1829) was the first president to opt for a hairier facial appearance. This new look consisted of something between very long sideburns and muttonchops. He may have been emulating his father’s [John Adams (1789–1803)] sideburns, which were shorter but just as bushy as his. Martin Van Buren (1837–1841) was next to show some facial flair, sporting long bushy sideburns, followed by Zachary Taylor (1849–1850), who wore shorter, less ostentatious but still bushy sideburns as well.

In 1861, the first beard appeared on the face of a president. The beard, sans mustache, appeared on the face of Abraham Lincoln. In October of the previous year, Lincoln had received a letter from a young girl advising him that he should grow some whiskers in order to enhance his appearance, as well as his chances of winning the election the following month. Although Lincoln expressed concern in his reply to the little girl that people might consider doing so “a silly affectation,” he started growing a beard shortly thereafter. On his inaugural trip to Washington, D.C., the following February, his train stopped in Westville, New York, the hometown of the little girl, Grace Bedell. He called her from the crowd and proudly showed her his full-grown beard, saying, “Gracie, look at my whiskers. I’ve been growing them for you.”

In 1865, Andrew Johnson, who became President after Lincoln’s assassination, was the last clean-shaven president until William McKinley took office in 1897.

During those intervening years, the choices varied considerably. Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877) wore a closely cropped, but full, beard and mustache. My favorite, by the way. (Maybe because it looks like mine.) Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–1881) likewise wore a full beard and mustache but most definitely not a closely cropped affair like Grant’s. His beard cascaded well over his celluloid collar, just as his mustache flowed over his mouth, almost concealing it completely.

James A. Garfield (1881–1881) was only in office six months when he became the second president to be assassinated in less than 20 years. While in office, though, he perpetuated the style of his predecessor with a free-flowing mane of his own, beard and mustache alike. At least you could make out his mouth.

Chester A. Arthur (1881–1885) distinguished himself as the only president to adorn his countenance with the combination of muttonchops and mustache. Unfortunately, the hair on his face grew sparsely so he really wasn’t able to rock the style statement.

Grover Cleveland, the only president to serve two nonconsecutive terms (1885–1889 and 1893–1897), wore only a full mustache. It was a bushy one, one that seemed to eschew trimming, but not on the scale of those belonging to Hayes and Garfield.

Then there was Benjamin Harrison’s (1893-1897) beard. Similar to Grant’s in shape and length and well groomed, it also earns style points for color. Although he was only 56 years of age when he took office, his beard was totally white. I still like Grant’s the best. (Did I mention that his looked like mine?) As a result of yet another assassination, Teddy Roosevelt became president in 1901. William McKinley (1897-1901) had opted against any type of facial hair at all, but his successor wore a full mustache similar in size and shape to Cleveland’s. In today’s parlance, both Teddy’s and Grover’s mustaches would be likened to those of bull walruses, and come to think of it, probably were in their day as well.

The last president to adorn himself with facial hair was William Howard Taft (1909-1913). His choice was a full-blown handlebar mustache.

So why have the presidents’ faces gone hairless for over a hundred years? Around the turn of the 20th century, public health officials determined that tuberculosis, a scourge of the era, was an infectious rather than a hereditary disease. In this period of uncertainty about the disease, the theory arose that men’s beards could be repositories of tuberculosis germs. That pronouncement eventually led to the adoption of the clean-shaven look as the more healthful and therefore more desirable for presidential candidates, as well as men in general. Even after it was determined that beards posed no greater risk of contracting or transmitting tuberculosis than shaven skin, the damage was done. Facial hair didn’t return to men’s faces until the 1960s and never again (or at least not yet) to the faces of presidents.

In the presidential races of 1944 and 1948, Thomas Dewey, the last candidate for the office to wear facial hair, was defeated on both occasions. It was said at the time that the public’s disapproval of his mustache may have contributed to his losses.

So, is that it? Has presidential facial hair been relegated to the dustbin of history? I don’t think so. If Julian Edelman, the MVP of Super Bowl LIII, can wear a beard and have it shaved live on TV by Ellen DeGeneres, can the most powerful chief executive in the world be far behind?

Maybe, if it’s a woman. PS

Scott Sheffield moved to the Sandhills from Northern Virginia in 2004. He feels like a native but understands he can never be one.