Where art meets industry, in a world of gritty timelessness

By Jim Moriarty • Photographs by Laura Gingerich

Dressed like Marty McFly paying a nocturnal visit on his adolescent father in Back to the Future, Brian Brown and Jackson Jennings shuffle along in their silver coats and hoods with plastic face shields, carrying 270 pounds of molten bronze as if it was the industrial version of Cleopatra’s golden litter. As they tip the glowing bucket, orange metal flows like lava into the gray-white ceramic casts wired in place in a steel pan on the cement floor. This is how Ronald Reagan got to the Capitol rotunda.

Carolina Bronze Sculpture, hidden down a gravel drive past Maple Springs Baptist Church on the other side of I-73 from Seagrove’s famous potteries, may be the foremost artists’ foundry in the eastern United States. Certainly it’s the one most often used by Chas Fagan, the Charlotte artist whose statue of Reagan resides in the people’s house in Washington, D.C.

The foundry is the life’s work of Ed Walker, 62, a quiet, unassuming man with a quick smile and a knack for noodling on an industrial scale. Walker is a sculptor, too. His “Firefighter Memorial” in Wilmington, North Carolina, incorporating a piece of I-beam from the South Tower of the World Trade Center, was completed in 2013, and he hopes to have the recently announced Richard Petty Tribute Park with multiple sculptures completed in time to celebrate Petty’s 80th birthday on July 2. One of Walker’s large abstracts is on its way to Charleston, South Carolina, on loan for a year’s exhibition.

“Ed’s a rare combination of a complete artist’s eye mixed with an absolute engineer’s brain,” says Fagan. “He’s the kind of guy who can solve any problem — and every project has a list of them. Nothing fazes him.”

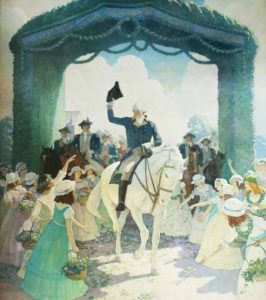

Take Fagan’s sculpture “The Spirit of Mecklenburg,” a bronze of Captain James Jack on horseback, the centerpiece of a fountain in Uptown Charlotte. “The design was not easy,” says Fagan of the 1 1/2 life-size bronze. “I had the thing leaning and he’s at full speed so the horse’s feet are not on the ground exactly. Engineers had to be involved, at least two of them, maybe three. We’re all standing around this big clay horse and a question popped up on something pretty important. Everyone pipes in, pipes in, pipes in. Eventually Ed offers his opinion in his normal, subdued, quiet manner. Then the discussion goes on and on and on, the whole day. Magically, everything circled around all the way back to exactly what Ed had said. I just smiled.”

Walker grew up in Burlington, living in the same house — three down from the city park — until he graduated from Walter M. Williams High School and went to East Carolina University. His father, Raleigh, was a WWII veteran who developed a hair-cutting sideline to his motor pool duties in the 5th Army Air Corps. “There was a picture he showed me of this barbershop tent, and Dwight Eisenhower and Winston Churchill were standing out in front of it. They’d just gotten a shave and a haircut by him, and he was on the edge of the photo.” The same shears kept Ed’s head trimmed, too.

Walker was drafted by art early on. He turned pro when he was in first grade. “Back then kids didn’t have money, at least not in my neighborhood,” he says. “My mom and dad (Lillie and Raleigh, who both worked in the textile mills) thought that ice cream was something you get on Friday for being good all week.” Others got it more frequently. Walker started drawing characters taken from classroom stories using crayons on brown paper hand towels, then trading them for ice cream money. Goldilocks. The Three Bears. Not exactly “Perseus with the Head of Medusa” but, heck, it was just first grade. Soon, he was coming home with more money than he left with in the morning. “My mom questioned me about it. The next day I had to go to the principal’s office and was told that under no circumstances could I be selling something on school grounds.”

Sculpture reared its head at ECU. “I took my first sculpture appreciation class with Bob Edmisten. Had my first little bronze casting from that class. They pushed everybody to explore. You could use or do anything. I fell in love with that. Started learning how to weld and cast and carve, the kind of range of things you could do.” In addition to getting a Bachelor of Fine Arts, Walker met his wife, Melissa, another art major, also from Burlington.

“We knew each other in high school,” says Melissa.

“She was in the good student end,” says Ed. “I was in the back with all the problem people.” The old art building at ECU was near the student center. She was going out. He was going in. They were pushing on the same door in different directions. By their senior year they were married.

The first stop after graduation was Grand Forks, North Dakota. If you’ve been to North Dakota, you know there are months and months of harsh winter followed by, say, Tuesday, which is followed by more winter. The University of North Dakota was interested in setting up an art foundry and offered a full stipend to the person who could do it. Walker had helped Edmiston put together the one at ECU’s then-new Jenkins Fine Arts Center. The professor recommended the student. North Dakota sent the Walkers a telegram — your grandfather’s instant messaging. Be here in two weeks. They were.

“They had a new building and a bunch of equipment in crates,” says Walker. “Figure it out. Set it up.” Walker’s art history professor at UND was Jackie McElroy, better known today by the pseudonym Nora Barker, a writer of cozy mysteries, who reinforced his belief that you could figure out how to do just about anything if you wanted to badly enough. It became a recurring theme.

Chased out of North Dakota with a master’s degree and a case of frostbite, the Walkers found themselves back in North Carolina trying to land teaching jobs. After traveling to a conference, essentially a job fair, in New Orleans, Ed and a friend, Barry Bailey, made a pact. If they didn’t have jobs in a year, they’d move to New Orleans. They didn’t and they did.

The Walkers arrived on July 3rd, dead broke. They slept on the floor of the apartment of a friend of their friend, Barry. “We had no job to go to, no food, no money,” says Walker. The next day at a Fourth of July block party, he picked up some carpentry work building a Catholic church. It lasted the rest of the steamy Louisiana summer. The couple attended art openings, went to galleries, met people. Walker got a gig as a bartender at a private party thrown by a local sculptor, Lin Emery. “At the end of the thing, she gave us a tour of her home and her studio,” says Walker. A creator of high-end kinetic sculptures, Emery mentioned she’d just lost her fabricator and was swamped with jobs that needed doing. “Do you know anybody who knows how to weld aluminum?” she asked. “Well, I can,” said Walker. He’d never done it before.

With a weekend to learn how to TIG (tungsten inert gas) weld, a professor friend introduced him to a guy in the maintenance department at Loyola University who offered to help. Walker showed up for work on Monday. “I did not confide to her that I lied my way into the job until about eight months later,” he says. He worked in Emery’s studio until — with Emery’s help — he was able to mix and match enough bits and pieces of teaching jobs to laissez les bon temps rouler. Part time at Loyola. Part time at Delgado Community College. Part time at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Part time at Tulane University. Then, finally, a full-time job teaching sculpture at Tulane. “I had eight students,” Walker says of his first year. “In five years it went from eight students to 101 and eight sculpture majors.” But, as it turned out, Walker was more interested in sculpture than Tulane was.

The Walkers had purchased a single shotgun house with 12-foot ceilings built in 1876 in the Ninth Ward, east of the French Quarter, two blocks from the Industrial Canal that would fail when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. Ed created his own little foundry in the side yard. When he wasn’t tenured by Tulane in ’87, his little foundry became his business, initially casting bronze pieces for his students who suddenly had no place to complete their projects. By the fall of ’89, Melissa and their children, Sage and Nathan, moved back to North Carolina when Melissa got a job teaching art in Randolph County. Ed followed six months later. He fired up the foundry again in a building on North Fayetteville Street in Asheboro. In ’94 they bought 55 acres outside of Seagrove with a mobile home on the back corner. Carolina Bronze had a permanent place to live, one that they’re expanding to include what is, essentially, an outdoor gallery for large sculpture. It already has nearly 20 pieces in it, only a few of which are Walker’s. “We’re just getting going on it,” he says. “It’s not just to look at sculpture but to shop for it. It’s going to be a community park, too.”

Since moving to its current location in ’95, the foundry has produced works of art for hundreds of sculptors, the best known of whom is probably Fagan. “He is a person I know will be in the history books one day,” says Walker. “He’s done so many notable people.”

Fagan shares Walker’s penchant for figuring things out. He’s a 1988 graduate of Yale who majored in, of all things, Soviet studies. He took a couple of painting classes while he was in New Haven, and it turned out he had the one thing you can neither invent nor hide, talent. He says his work at the moment is mostly historical in nature. “I’m looking at a life-size seated James Madison. He’s in a 4-foot by 7-foot canvas,” says Fagan. While that commission was private, he had previously been hired by the White House Historical Association to paint all 45 U.S. Presidents. He did the portrait of Mother Teresa that was mounted on a mural and displayed during her sainthood canonization by Pope Francis. His sculptures include the Bush presidents, George H.W. and George W., shown together, and George H.W. alone; several versions of Reagan for Washington, D.C., London and Reagan National Airport; Ronald and Nancy Reagan for his presidential library; Saint John Paul II for the shrine in Washington, D.C.; and Neil Armstrong for Purdue University. The piece currently being produced at Carolina Bronze is a sculpture of Bob McNair, the owner of the NFL’s Houston Texans.

Fagan’s start in sculpture was, in its way, as unusual as studying Russia to master oil painting. While he was at the White House working on Barbara Bush’s portrait, he was asked if he could do a sculpture of George H.W., too. Sure, he said. Fagan had never done one before. Now the path to many of his finished pieces passes through Carolina Bronze.

“In this place I think we created a really nice marriage of modern technology and old school techniques that have been around for thousands of years,” says Walker.

Once a sculpture is approved and the project is on, an artist like Fagan will deliver a clay maquette, roughly a 2-foot version of the piece, to Walker. “From that Ed would determine how difficult it would be to make,” says Fagan. “I’m sure in his mind he’s planning out every major chess move along the way, because they are chess moves.”

David Hagan, a sculptor himself who works mostly in granite and marble, will produce a 360 degree scan of the piece, a process that takes about a day. That digital information is fed into a machine that cuts pieces of industrial foam to be assembled into a rough version of the sculpture at its eventual scale. “It’s at that point that I come in with clay and sculpt away,” says Fagan. “You’re at your final size and it’s a fairly close version of what you had, which may or may not be a good thing. What looks so great at a small scale may end up being not so great. You can have awful proportion things wrong. The foam that’s used is a wonderful structural foam that you can slice with a blade. For me, you can sculpt that stuff.” The eventual layer of clay on the foam varies according to the artist’s desire.

Several intermediate steps eventually yield a wax version of the sculpture, except in pieces. “For the artist, you gotta go back in and play with that piece — or the piece of your piece — the head or a hand or an arm or something,” says Fagan. “They’re all designed or cut based on where Ed, foreseeing the chess moves, figured out what’s going to pour and how. The maximum size of the mold is dictated by the maximum size of the pour. Those are your limitations, so you have to break up the piece into those portions.”

Solid bars of wax, sprues, are added to the wax pieces to allow for the passage of molten bronze and the escape of gases. A wax funnel is put in place. Everything is covered in what becomes a hard ceramic coating. That’s heated to around 1,100 degrees. The wax melts away. Brown, who has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from UNCG and whose own bronze sculpture of a mother ocelot and kittens will go on display at the North Carolina Zoo this year, slags the impurities off the top of the molten bronze. It’s poured at roughly 2,100 degrees. “I found that I enjoyed the more physical aspect of working with sculpture as opposed to doing drawings or paintings,” says Brown.

After everything has cooled and the ceramic is broken away, the pieces need to be welded together to reform the full sculpture. “The weld marks on the metal, you have to fake to look like clay,” says Fagan. The artist oversees that, as well. “The bronze shrinks but not always at the exact same percentage. There are always adjustments.” The last step is applying the patina, one of a variety of chemical surface coatings, done at Carolina Bronze by Neil King. Different patinas are chosen for different reasons: if the piece is to be displayed in the elements; if it will be touched frequently; and so on. “For someone like the artist who is very visual, it’s hard to imagine what the end result is going to be when you see the process. It will just look completely different in the middle than it will at the end. It’s an absolute art,” says Fagan. When it’s finished, no one knows the structural strengths and weaknesses of the sculpture better than Walker. They crate it like swaddling an infant, put it in traction, and then ship it off.

In a digital world where so many things seem to have the lifespan of magician’s flash paper, a foundry is a world of gritty timelessness. “Because we do a lot of historical things here,” says Walker, “we get to make permanent snapshots of points in time.” At the end of the day, whether they’ve poured brass bases for miniaturized busts of Gen.George Marshall or pieces of a torso for a presidential library, the kiln and furnace go cold. Like any other small factory, the doors are locked and everyone goes home. Except for Walker. These are the hours he gets to spend alone shaping a bas relief of Richard Petty’s greatest hits. As George McFly said to Marty when his first novel, A Match Made in Space, arrived, “Like I’ve always told you, you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.” PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.