On the trail of Flora MacDonald’s offspring

By Bill Case

If you are a Showtime viewer, odds are you are familiar with the show Outlander, a time travel odyssey in which the 20th century female protagonist, Clare, after touching an ancient standing stone, is mystically transported to mid-18th century Scotland. Though married in her 20th century life, Clare weds Highland Scot Jamie Fraser, and given the circumstances, her bigamy seems excusable.

Clare and Jamie share adventures in a time of historic upheaval as the Jacobite Rebellion is in full swing. The charismatic Charles Edward Stuart, popularly known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” is engaged in an ultimately futile quest to restore the Stuarts as Britain’s monarchial rulers. Primarily due to the Stuarts’ adherence to the Catholic faith, Parliament had removed Charles’ grandfather, James II, from the throne a half-century earlier.

The Bonnie Prince courts support for his cause from French royalty and Scottish Highland clans in hopes they will back his effort to dethrone England’s current king, George II, and restore the Stuarts. Clare knows her history and is fully aware that the uprising is not only doomed to failure but will also result in devastation to the clans but, as is usually the case with transtemporal travel sagas, the Frasers’ various schemes to alter history backfire, making the foretold result inexorably more certain.

The Battle of Culloden on April 14, 1746, represents the denouement. The Highlanders are routed, and their catastrophic defeat effectively brings an end to the rebellion. But Outlander does not address the post-Culloden story of how a young Scottish woman cleverly aided Bonnie Prince Charlie’s desperate effort to escape British capture.

At the time of Culloden, Flora Macdonald was 24 years old. She was living off the northwest coast of Scotland on the Isle of Skye with her financially well-off mother and stepfather, Hugh Macdonald. One acquaintance described her as “a woman of soft features, gentle manners, kind soul, and elegant presence.” On June 20, 1746, Flora was visiting her brother at his “shieling” (huts where cattle farmers stay when tending to their livestock) on the neighboring island of South Uist.

It so happened that the on-the-lam prince was hiding nearby in the company of two aides, Capt. Conn O’Neill and Neil MacEachen. The king’s forces were hot on Charles’ trail, having organized search parties to apprehend the man they called the “Young Pretender.” Flora’s stepfather, Hugh Macdonald, secretly sympathetic to the Jacobites, informed the prince through a third party that Flora could be useful in affecting Charles’ potential escape by boat to Skye, where arrangements were in the works to transport the prince to France and freedom.

O’Neill, leaving behind Charles and MacEachen in the hills nearby, greeted Flora at the shieling late one night, and conspiratorially inquired whether he could “bring a friend to see her.”

Flora responded, “Is it the prince?”

Minutes later, Charles was before her. A plan had been concocted. Flora would sail home to Skye in an open boat accompanied by MacEachen and Charles, who would be disguised as a woman and use the alias “Betty Burke.” The “maid’s” purported purpose for traveling to Skye would be to spin wool for Flora’s mother. Flora’s stepfather, a double agent in the affair, as he also occupied a position in the British military, would arrange passports for the three travelers.

Numerous facts of Flora’s life have been subject to varying interpretations by historians, and her eagerness to participate in the plot is one of them. According to MacEachen, Flora agreed to the proposal immediately. O’Neill, however, reported that the young woman was far more ambivalent because of the obvious dangers of the enterprise. He claimed he overcame Flora’s hesitancy by declaring she “would be made immortal by such a noble and humane deed on her part in the Prince’s distressing circumstances.”

Flora proved to be no shrinking violet. She adamantly rejected the prince’s demand to include O’Neill on the voyage — she carried passports for just three passengers — and just as sternly refused Charles’ plea to carry a gun.

The crossing to Skye was launched from Benbecula on June 28. The voyage is recalled in the lyrics of the haunting ballad that opens each episode of Outlander — the “Skye Boat Song.” Strong westerly winds, high waves and fog plagued the rowers, and the boat was fired upon by hostile militia as the craft sought to make land at Skye. But Flora and her companions managed to avert disaster and put in elsewhere on Skye, where Alexander MacDonald of Kingsburgh took charge of Charles. When the grateful Bonnie Prince bade goodbye to Flora at Portree, he is supposed to have said, “I hope, Madam, we shall meet in St. James’s yet.” In short order, Charles jumped aboard another boat to Raasay from where he would eventually make his way to France. Notwithstanding his narrow escape, Charles Stuart was destined to live in exile the remainder of his increasingly sad and dissolute existence.

Flora, however, failed to elude the authorities. After word leaked regarding her role in Charles’ escape, she was detained and held as a prisoner, eventually taken to London in December 1746. Aside from a brief stint in the Tower of London, Flora, though technically under house arrest, enjoyed relative freedom in the city, visiting friends and entertaining visitors. O’Neill’s prediction that assisting the Bonnie Prince would lead to her lasting fame was coming true. She became a cult hero to Jacobite devotees. One woman asked Flora whether she could “have the honor of lying in the same bed with that person who had been so happy as to be guardian to her Prince.” Even royal partisans found themselves charmed by Flora. Frederick, Prince of Wales, paid her a personal visit.

Released from detention in July 1747, Flora returned to Scotland, resettling on Skye. In 1750, she married Allan MacDonald of Kingsburgh, the son of the man who had taken custody of Charles following the prince’s escape to Skye. Flora and Allan would parent seven children. Five years after their marriage, Allan succeeded his father as manager of their patron’s estate holdings. Unfortunately, he lacked business acumen and that, coupled with a cattle disease epidemic, led to Allan’s dismissal around 1766.

Facing increasingly difficult circumstances, the MacDonalds decided in 1774 to follow the example of fellow countrymen who had emigrated to North Carolina. Allan and Flora, along with sons Alexander and James, daughter Anne, her husband, Alexander MacLeod, and their children sailed to Wilmington, North Carolina, aboard the Baliol. Flora and Allan’s sons Charles and Ranald, engaged in military service for the crown, did not emigrate. Son John and daughter Fanny remained in Britain.

Flora and Allan first settled at Cross Creek, present-day Fayetteville. They subsequently moved farther west, acquiring a 475-acre plantation about 5 miles from Norman, North Carolina. Soon after Flora and Allan moved to their new estate, the Revolutionary War began. A majority of North Carolina’s Scottish Highlanders sided with the crown, as did Flora and Allan. Flora’s segue in allegiance from the Jacobites to the Hanoverian monarchy may appear puzzling, but most Highlanders had little stomach for taking on the powerful British Army following the debacle of Culloden. They figured allegiance to King George would be their best bet for avoiding a conflict that would disrupt their efforts to start over on the frontier.

Allan accepted a commission with the Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment, commanded by yet another “Mac,” Donald MacDonald. Allan’s sons Alexander and James, as well as son-in-law Alexander MacLeod, likewise joined the unit. The royal governor, Josiah Martin, ordered the regiment to gather at Cross Creek, then march to Brunswick, where it would link up with a brigade of British troops arriving from the North. The governor believed the combined forces would easily quash the Colonial rebellion in North Carolina.

Early Flora MacDonald historians maintained she was personally active in recruiting expat Highlanders for the regiment, delivering a rousing speech at Cross Creek exhorting the recruits to fight for victory over the rebels.

Colonial forces headed off the regiment on its march to Brunswick, confronting it at Moore’s Creek Bridge on Feb. 27, 1776. Shouting “For King George and Broadswords,” the Highlanders unwisely mounted a charge across the bridge. They were greeted with withering patriot gunfire. In the ensuing disaster, dozens of Scots were killed. Hundreds more were captured, including Allan MacDonald and son Alexander. The remaining members of the regiment, including James MacDonald, scattered. The crushed Loyalists would not re-emerge as a military presence in North Carolina until near the end of the war, in 1781.

The emboldened patriots (also called “Whigs”) began confiscating the land, livestock and other holdings of Scottish immigrants still loyal to the king. Flora did not escape the plundering. The plantation was ransacked and confiscated. She suffered the loss of most of her possessions. Desperate, she sought and received refuge in what is now Moore County under the protection of Loyalist Kenneth Black. In her new abode, located near the New River and present-day Pinehurst, Flora was close to daughter Anne, whose home, “Glendale,” stood nearby.

Summoned to appear before the local Whigs’ Committee of Safety to answer for her allegedly seditious conduct, Flora coolly displayed “spirited behavior” in responding to the inquiry. She was permitted to go free.

Allan managed to obtain freedom for himself and son Alexander by successfully negotiating a prisoner exchange with Congress in August 1777. He was released in New York, where he took command of a Loyalist company. In March 1778, Flora was permitted by Colonial authorities to join her husband there. Later that year, the couple made their way to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Allan was placed in command of another regiment.

Persuaded by her husband that she would be better off living her remaining years in Scotland where her hero status remained undiminished, Flora, then 57, and daughter Anne returned to her native land in 1779. En route, a French privateer attacked Flora’s ship. Legend has it that she mounted the deck, exposed herself to gunfire, and bravely cheered the crew’s successful effort to repel the attack. She broke her arm in the resulting melee but reached Skye, where she was reunited with daughter Fanny, by then age 14.

Completing his service obligation in 1784, Allan crossed the Atlantic to Scotland and Flora. Because siding with the Loyalists resulted in the forfeiture of his American property, he submitted a claim seeking compensation for those losses and was granted a partial award by the crown. His financial circumstances further improved after obtaining a property management role as “Tack of Peinduin.” The position enabled Allan and Flora to live in relative, financial comfort until Flora’s death in 1790. Allan passed away two years later. Both are buried in Kilmuir Cemetery on Skye.

Flora MacDonald’s life in North Carolina was replete with hardships, enduring lengthy separations from her husband, the harsh enmity of the Whigs, financial ruin, and virtual banishment from the state. A 1930s article in the Pinehurst Outlook disclosed another heartbreak allegedly suffered here. Citing a 1909 biography, the story claimed that after the fateful battle at Moore’s Creek Bridge, Flora “was called to grieve the loss of a son (age 11) and daughter (age 13) who died of typhus fever,” and that the two children were still buried at the MacDonald’s “Killiegray” plantation on Mountain Creek near Norman, North Carolina. A monument had been placed at the site marking the graves of her children.

While the text of the Outlook article acknowledged the graves, located in Richmond County just across the Montgomery County line, were “somewhat inaccessible,” it said they could be reached “without great difficulty,” and like an 87-year-old GPS, directions were provided. So, on a crisp mid-January afternoon, I drove to Norman. The directions said that “when almost through the village just beyond two brick churches, one on either side of the road, turn left on a dirt road.” I spotted the two churches and turned just beyond them, driving a couple of miles down a country road looking for the bridges and farm paths the Outlook said would lead to the graves. It was clear, however, that the passage of time had eradicated the helpful landmarks. I pulled over to contemplate my next move.

Just then, a young local couple drove alongside and asked if I was lost. When I explained I was looking for two Revolutionary War-era graves, the young man responded, “Oh, you mean the stones!” He suggested backtracking and veering down a crossing road that, as far as I could tell, didn’t exist. Where were these stones? Had the Outlander’s Clare Fraser experienced similar frustration when she sought to find the magical standing stone that would transport her from the 18th to the 20th century?

Reluctant to give up the hunt, I drove back into Norman and stopped at the local post office. (No dead letter jokes, please.) I told the longtime postmaster, Helen Simmons, about Flora’s children and “the stones,” and she smiled.

“I don’t know where Flora MacDonald’s children are buried, but I think I know what that fellow meant,” she said. “Tell you what, I’m getting off work. Follow me out of town to Mt. Carmel Presbyterian Church. It was founded by Scots who settled in this area during the Revolution. Several of my ancestors are buried there. There are some very old graves in the churchyard. Maybe you’ll find what you’re looking for there.”

Soon, Helen and I were walking about Mt. Carmel’s ancient graveyard. The black headstones from the late 1700s, worn down to the nub, some no more than 6 inches high, did not bear any decipherable script. If these were the “stones” my young acquaintance had had in mind, I doubted Flora’s children’s graves were among them. They were supposed to be located on private property — not in a church graveyard — though I did later learn that Flora attended the Mt. Carmel church during her abbreviated stay in the area.

I must be adept at appearing forlorn and in need of assistance, because after Helen left, another local resident came to offer help. Arriving in the church’s driveway was Bill McFadden, retired life-time Norman resident and a Mt. Carmel congregant. After hearing my tale of frustration, Bill placed a call to a historically-minded friend who suggested we look for the graves down another road that led into Richmond County. In short order, I was tailing Bill to another clearing in the countryside, but this foray didn’t pan out either, and the graves’ location remained a mystery.

It turned out that in 1937, three years after the Outlook article, what was left of the children’s bodies had been disinterred and reinterred at the Red Springs campus of Flora MacDonald College, now Highlander Academy. But why?

I toured the Red Springs campus with Alex Watson who explained that prior to 1915 it was a women’s college named Southern Presbyterian College and Conservancy of Music. Dr. Charles Vardell founded the institution in 1896 and served as its president for decades. Linda Rumple Vardell, Charles’ wife and an accomplished pianist, ran the college’s music program. Since the area had been settled by transplanted Scots, many Southern Presbyterian students were of Scottish ancestry.

When Canadian James A. Macdonald, editor of the Toronto Globe and an ordained Presbyterian minister, came to Fayetteville to attend a gathering of Scottish clans in 1914, he also toured the Southern Presbyterian College campus. Wowed by what he saw, the editor made a pledge to the endowment of the school and encouraged fellow Scots to do likewise. Macdonald felt that fundraising would be facilitated if the college’s scope was “broadened to bear the name of the Scottish heroine (Flora), herself a Presbyterian, a college graduate, and a noble example of Christian womanhood.” Thus in 1915, the Canadian persuaded Vardell to rename the school Flora MacDonald College, though the Presbyterian Synod of North Carolina still remained in ultimate charge.

The name change occurred not long after the publication of Flora MacDonald in America, by J.P. MacLean, in which the author claimed that Flora’s two children were buried at the aforementioned Killiegray plantation, approximately 50 miles from Red Springs. It occurred to Vardell that relocating the children’s graves on the Red Springs campus would provide the campus an additional element of Scottish heritage and testament to Flora’s memory.

But a legal obstacle stood in the way. Digging up a grave and relocating the remains was not a simple matter. The North Carolina legislature first needed to authorize any such disinterment. Before approaching the legislature, Vardell thought it prudent to undertake additional research to confirm that the graves were actually those of Flora’s children. To perform this task, Vardell turned to W.R. Coppedge, the highly respected former pastor of Mt. Carmel Presbyterian Church and superintendent of Richmond County Schools. Rev. Coppedge spoke with several longtime residents, all of whom believed the graves contained Flora’s children based on traditional accounts that were now a minimum of four generations old. Coppedge was persuaded that the residents knew what they were talking about and signed an affidavit indicating he was “convinced that these are the graves of Flora MacDonald’s children.”

Armed with Coppedge’s affidavit, Vardell obtained the legislature’s approval in 1917 to move the remains. For reasons unknown, the graves at Killiegray stayed undisturbed until the 1930s, when Vardell turned his attention back to bringing the graves’ remains to the campus. He was on the scene when they were finally dug up.

Vardell reported that natural elements and the passage of time had transformed the bodies into dust, which was collected in separate receptacles and brought to Red Springs. Corresponding with a project booster, an enthused Vardell wrote, “I think we can now say, so far as an intelligent person can judge, that the remains of Flora MacDonald’s children are now on the college campus.”

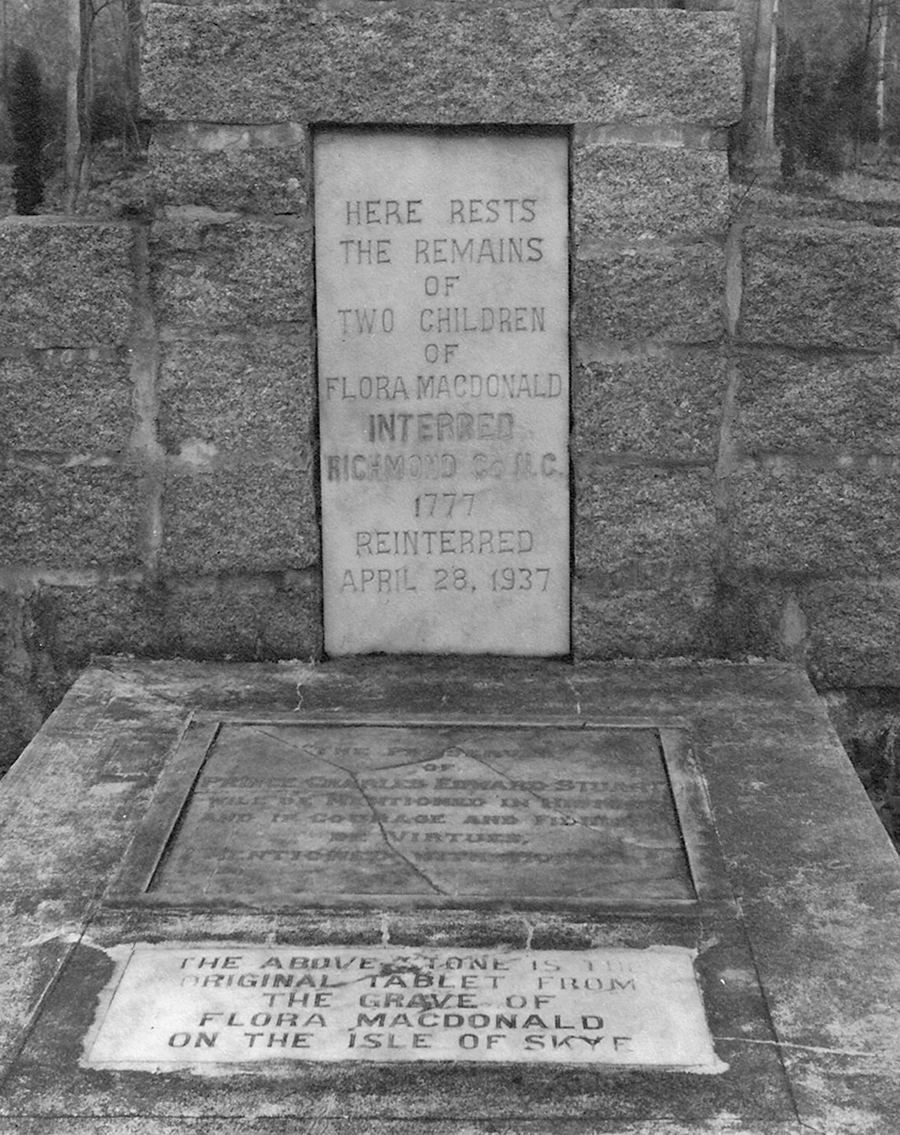

Having constructed a granite wall as a backdrop for the graves, the college made ready for an elaborate funeral ceremony at Red Springs on April 28, 1937. Prior to the ceremony, the double coffin was placed under the campus dome and laid “in state.” A 30-piece Fort Bragg military band and an honor guard of young women adorned in Stuart plaid lent a dignified atmosphere to the occasion. Four Flora MacDonald College students, all fittingly named Flora MacDonald, carried the remains from the dome to their permanent resting place.

Soon after the widely reported ceremony, questions were raised by skeptical historians whether the remains reinterred at the college were really Flora’s children. The naysayers advanced a simple argument that, in essence, involved the counting of noses: Flora had borne seven children, and they all could be accounted for. Sons Ranald and Alexander were lost at sea in 1783, and the earliest death of the remaining five took place in 1795 — 19 years after Flora fled the plantation.

Supporters of the view that the remains were of Flora’s offspring pointed to a letter she allegedly sent in February 1776, beseeching her friend Maggie to visit because Allan was with the regiment “and I shall be alone with my three bairns (Scottish word for children).” It was asserted that two of the “bairns” could only be the children who perished at the plantation. The 1872 edition of American Historical Review quoted this correspondence and stated it was being preserved in Fayetteville. But the letter’s existence is considered suspect since no one knows where it is today. Moreover, its slangy language is thought to be inconsistent with other writings of the well-educated Flora.

If two of Flora’s children did perish from typhus, it stands to reason she and Allan would have memorialized that fact somewhere in their writings. It would have particularly served Allan’s interest to report any such deaths in his 1784 petition to the British government in which he sought compensation for the confiscations and other losses he and Flora suffered in North Carolina. In his submission, Allan pulled out all the stops, pouring out the litany of hardships and heartbreaks inflicted upon the MacDonalds while in America, including the loss at sea of son Ranald. Tellingly missing from the petition is any mention of deaths of other children, young or otherwise.

Research of Colonial-era property records by Pinehurst’s Rassie Wicker further weakened the frayed case that the graves contained Flora’s children. Wicker found that Allan MacDonald never owned land at or very near Mountain Creek, the site of the unearthed graves. He did, however, own a 475-acre plantation in Montgomery County about 4 miles away on Cheek’s Creek. A 1775 letter authored by Royal Gov. Martin buttresses Wicker’s position. Martin wrote that he intended to spend the summer “with my friend Mr. MacDonald of Kingsborough … on Cheek’s Creek.” Wicker made the additional point that had Alan been inclined to name his plantation, he would surely have called it Kingsborough, not Killiegray — a name associated with a different Scottish clan.

This historical brouhaha failed to generate much impact at Flora MacDonald as the college refrained from involving itself in the controversy while continuing to project a spirited Scottish motif throughout the two decades following the aforementioned 1937 funeral. The college faced a far more significant challenge in 1955, when the Presbyterian Synod decided to consolidate the operations of various colleges they had been supporting. As a result, Flora MacDonald College and Presbyterian Junior College in Maxton were combined into a co-educational institution and moved to Laurinburg. The resulting school subsequently became St. Andrews University.

Flora MacDonald College was closed in 1961 and its personal property, including valuable paintings, a pearl brooch reportedly containing a locket of the Bonnie Prince’s hair, a snuff box given by Allan to Flora on their wedding day, and other artifacts, were packed up and shipped to Laurinburg. Nothing was left of the school in Red Springs except its vacant and rapidly deteriorating campus buildings.

The vacating of the campus devastated the community of Red Springs and the college’s female alumni. A combined preparatory school and junior college was reopened at the campus three years later. In 1974, the institution became a K-12 co-ed school. While undergoing multiple name changes since the 1961 reopening, the school has continued to venerate its Scottish heritage, Flora MacDonald, and her putative children.

But if, as seems most likely, the remains of Flora’s children are not housed in the campus graves, whose are they? It is doubtful anyone will ever know with certainty, but presumably they are children of either early Scottish immigrants or slaves. But there is no question about the authenticity of the damaged marble tablet that the college placed on the graves. It originally graced the monument on Flora’s gravesite on Skye. After a storm damaged that monument, Charles Vardell helped raise funds to replace it, journeying to Scotland for the installation of the new stone. He was permitted to return to Red Springs with the original tablet, which bore the following inscription:

FLORA MACDONALD

Preserver of Prince Charles Edward Stuart

Her name will be mentioned in history,

and if courage and fidelity be virtues,

mentioned with honour. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.