The Creators of N.C.

The Adventurous Child

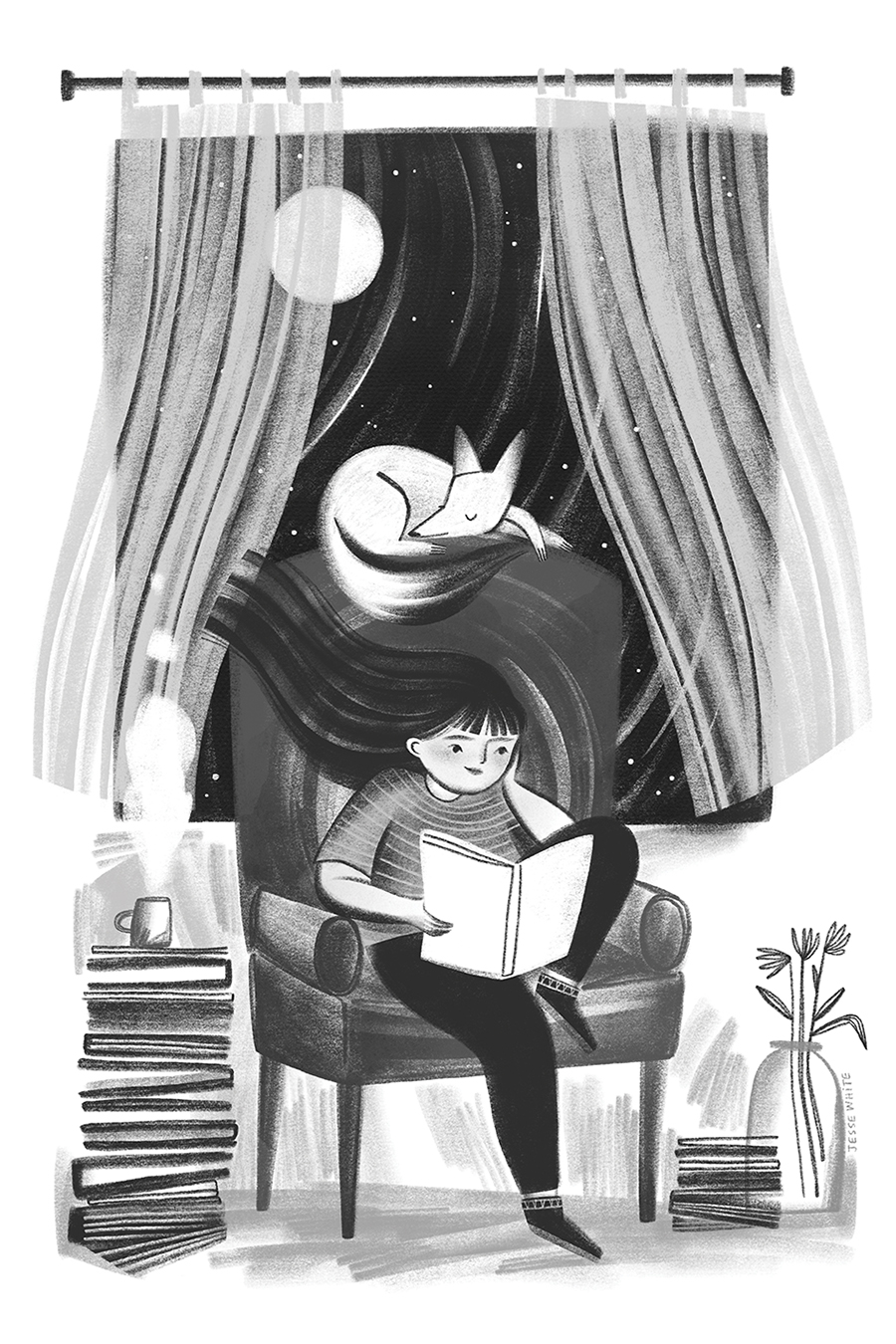

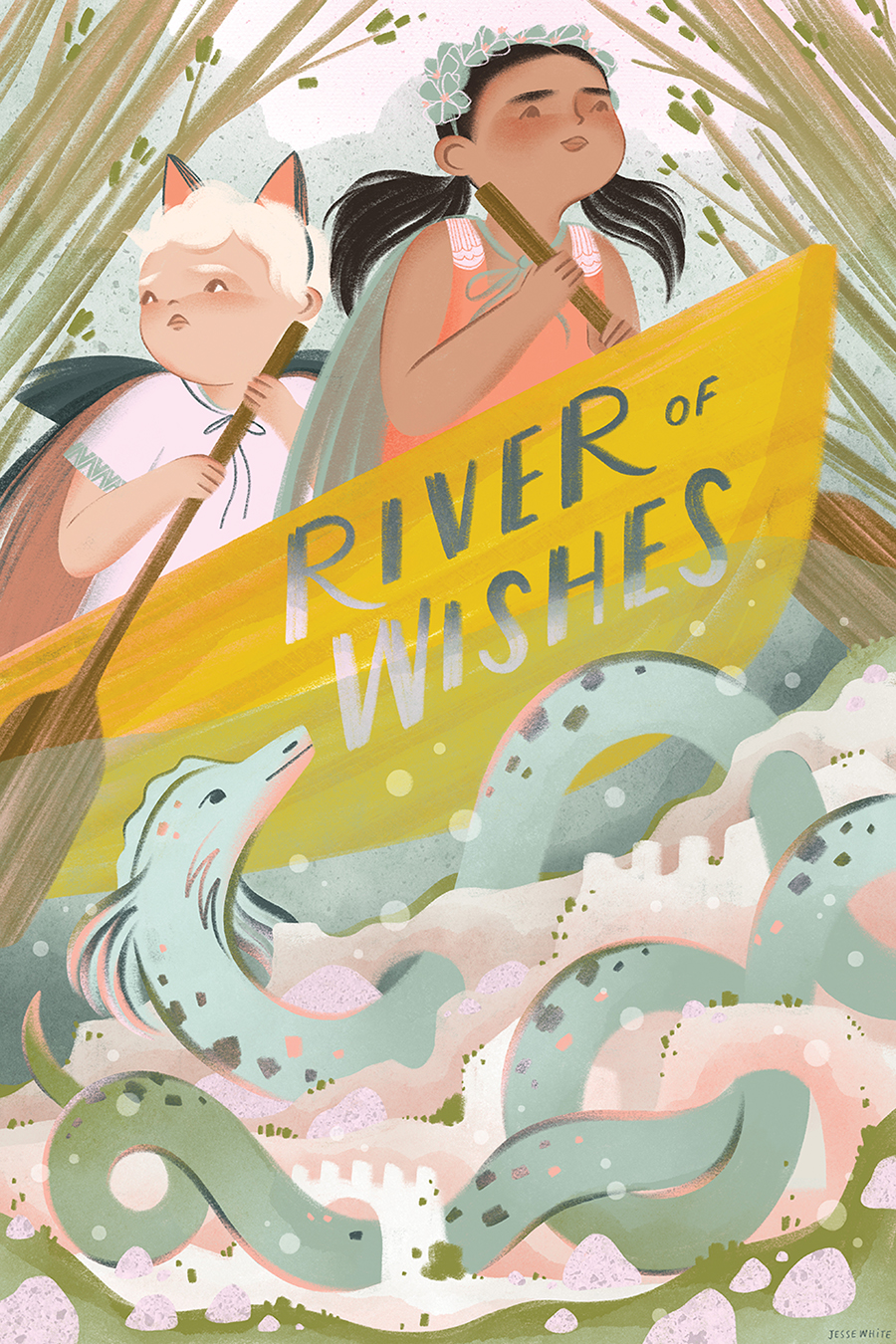

Illustrator Jesse White’s major minors

By Wiley Cash

Photographs By Mallory Cash

When former teacher Jesse White discovered that her young students’ personalities and identities weren’t reflected in the teaching materials she was provided, she decided to take their education into her own hands, literally: She drew all of her classroom materials by hand in an effort to bring their lives more into her classroom. White, who is now a full-time illustrator, hoped her efforts conveyed how much she valued and believed in each child and how they saw themselves represented in the world. This conviction to portray the world as children see themselves in it comes from her own childhood outside Siler City, where she grew up with her mother, Gwen Overturf, and her father, Eddie White, on 10 acres of land along the Rocky River.

“Childhood is a primary inspiration for me,” she says on a bright afternoon at her home in Durham. “I’m someone who loves nostalgia and likes thinking about ways that we can reconnect with our childhood or just the child inside of us. And so that’s what I do all day; I go back to little Jesse, who was spending a lot of time in the woods with my mom and by myself exploring the rocks near our house, coming up with games, ideas and secret missions that I would go on. My primary inspiration is my childhood and the time that I spent outside in nature.”

Jesse was home-schooled until second grade and spent a lot of time accompanying her mother to various jobs where she worked in landscaping and at a goat dairy. She was left free to explore.

“I would spend a ton of time with the dog and the goats, and go wandering off into the woods.”

When her mother began teaching at the former Community Independent School, Jesse followed. And then she was off to public school for middle and high school.

“I’ve had a pretty big range of educational experiences. Looking back on it, even though there were some difficult transitions, I wouldn’t trade, it for sure. I value a lot of what I picked up and learned at each of those different types of schools,” she says.

But she felt different from other kids. After years of learning to milk goats, roaming the woods and developing elaborate games on her own, how could she not? As an artist, she was more intent on drawing the natural world than superheroes or Barbies.

“I was drawing stuff that my classmates had never really seen before,” she says. “So maybe that’s where that difference showed up.”

Jesse gained inspiration not only from the woods around her, but also from her parents, both of whom were arts-oriented. Her mother, Gwen, had a background in graphic design and experience in education. Although Eddie, her father, had a background in graphic design as well, he designed and built houses for much of her childhood. When she was in middle school, he shifted away from construction and became a full-time artist, creating large-scale metal sculptures and installations, including one for the Hilton Hotel in Kuala Lumpur.

It was in college at UNC-Chapel Hill that Jesse first considered pursuing a career in arts education.

“It was this wonderful answer to what had been missing for me,” she says. “I enjoyed making art, but I was like, ‘Man, this is missing a social aspect somehow. What can I be doing to use this to engage people and help them reflect on their own identities and their own lives and their own learning?’ And so art education blew my mind in that way. I could not only make art, but I could facilitate learning through art.”

Fresh out of graduate school, the first time she stepped into her own classroom, Jesse admits to having “life altering lessons” that she planned to present to her students. She quickly found that having a class of 25 to 32 kids was as much about function as it was creativity. But she absolutely loved it. “It was one of the most exciting and rewarding things that I’ve ever done,” she says, and by her second year she had learned how to balance the practical demands of curriculum and classroom management with her creative ideas on how to engage students.

After four years in the classroom, she decided to go out on her own and pursue a full-time career as an illustrator. Once she focused on her own art, she recalled the power of creating the materials that represented who her students knew themselves to be and the ways in which she once saw herself as a young girl who thrived in the outdoors. The results were illustration after illustration of young girls exploring natural landscapes, much like Jesse had.

“I don’t know why it took me so long to realize this,” she says, smiling, “but I just don’t draw kids inside very much.”

A quick perusal of her website or Instagram page reveals this to be true. In one illustration, a little girl in a rainslicker peers over the bow of a storm-tossed ship, the tentacles of a sea monster snaking below her. In another, a girl sits comfortably atop a rock and pours a cup of tea, a blue snake encircling her neck.

Jesse’s work also reveals a lack of adult characters, something others — including the editors of her forthcoming book, Brave Like Fireweed, which she both wrote and illustrated — have brought to her attention.

“‘We can’t have these kids just wandering by themselves out in the middle of nowhere without any adult supervision,’” she says, paraphrasing her editors. “I totally get that. But a huge focus and motivation for my artwork is to show kids as the capable and intelligent and independent beings that they are, and that doesn’t always require having an adult presence in order to be like that.”

People might also wonder where all the boys are because Jesse’s main characters are primarily young girls. “I’ve always found it to be incredibly important to include girls in my work who are outside, playing, exploring, adventuring, just because that’s not something that they’re always allowed or encouraged to do,” she says. “It’s something that I was allowed and encouraged to do, and that became a really important part of who I am.”

Studies examining children’s books of the past 60 years show that not only have boys been better represented than girls, but girls have also been portrayed as more emotional and less likely to engage in adventurous exploration.

Viewing Jesse’s work, it’s not hard to imagine these girls leaping from the page and striking out for places as yet undiscovered. And it’s not hard to imagine young Jesse doing the same. She still is. PS

Wiley Cash is the Alumni Author-in-Residence at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. His new novel, When Ghosts Come Home, is available wherever books are sold.