Film star Gloria Swanson dazzled the Sandhills, making a movie here in 1926

By Bill Case

Well before the clock struck midnight ushering in the new year of 1926, Pinehurst was abuzz with the report that a film crew from Paramount Pictures would be visiting the Sandhills in short order to film several scenes for a new movie. Even more electrifying was the news that Gloria Swanson, arguably Hollywood’s biggest star, had been cast in the film’s lead role.

The presence of Swanson’s name on theater marquees had guaranteed blockbuster profits for Paramount in the 26 silent films she had made for the company. Most of these movies were produced and directed by the studio’s legendary filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille. It was DeMille who had lured Swanson to Paramount in 1918, having been mesmerized by young Gloria’s alluring screen presence, first noted in Mack Sennett comedies, and then wasted in worse than mediocre films made by a lesser studio. DeMille realized that the 4-foot-11 Swanson was not a prototypical bombshell beauty. Much of her appeal stemmed from the unmatchable glamour and elegance she naturally projected on screen. DeMille capitalized on these qualities by branding Swanson as the ultimate clotheshorse.

Women focused on Swanson’s attire and appearance and flocked to the cinema to see Gloria adorned in the latest (and sometimes over-the-top) styles. Whether ornamented in peacock or ostrich feathers, turbans, jewels or beads, she defined chic. Swanson’s haute couture attire definitely influenced women’s fashions in the ’20s. Her captivating appearance coupled with torrid on-screen romances with heartthrob actors like Rudolph Valentino and Wallace Reid made for an irresistible combination for moviegoers. Swanson’s success had given her considerable leverage in dealings with Paramount, which now compensated her upward of $20,000 weekly.

The Hollywood star’s love life also provided considerable grist for the movie tabloids. The 26-year-old had already been married three times — the first at age 17 to fellow actor Wallace Beery, who subsequently became an A-list star himself. She separated from Beery a year later, asserting in her memoir that Beery physically abused her. Swanson’s second marriage, in 1920, to film producer Herbert Somborn seemed more a business arrangement than the product of a love affair. The couple did parent a daughter, also named Gloria, and adopted a son, Joseph, during their union. But that marriage crumbled also. The ink on the divorce decree was barely dry when in January 1925, Gloria married her third husband in France. A member of French nobility, Henri de la Falaise, Marquis de la Coudraye, had met Gloria while serving as her interpreter during the filming of Madame Sans-Gene. Handsome, attentive and multilingual, Henri was an authentic war hero, having demonstrated valor fighting for France in the trenches during The Great War. His status as a marquis allowed Swanson to enhance her already regal stature in show business with a title of her own. The only marital box that Henri could not check was the one marked “finances.” He had very little money of his own despite the fact that his mother was a scion of the Hennessy cognac family. Still, it seemed the couple was well matched and that Gloria’s heretofore turbulent personal life would culminate in a fairy-tale ending. Henri would accompany his wife, the “Marquise,” to Pinehurst for the filming.

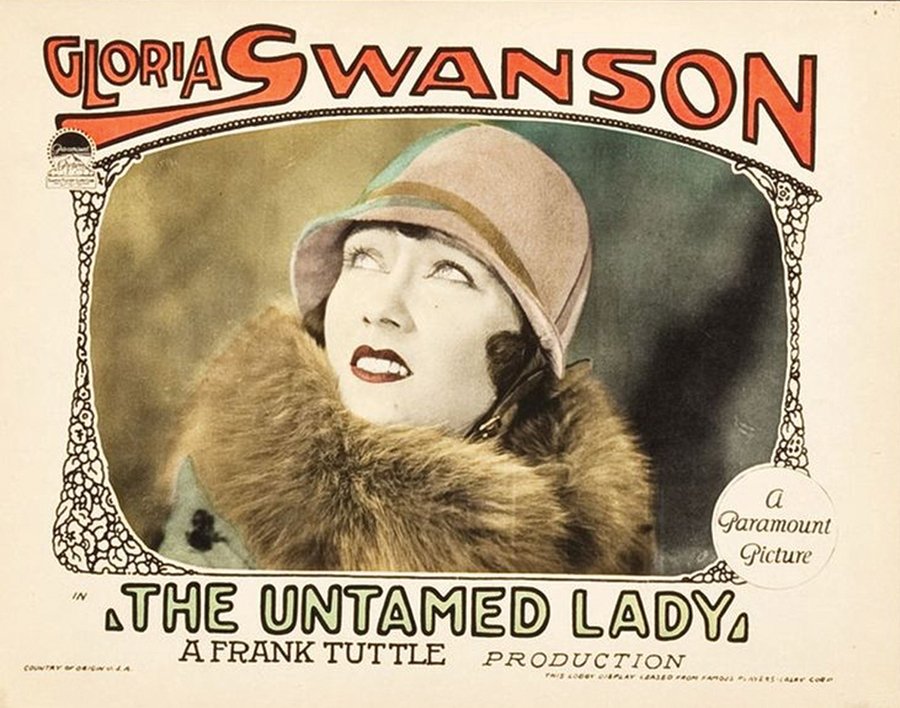

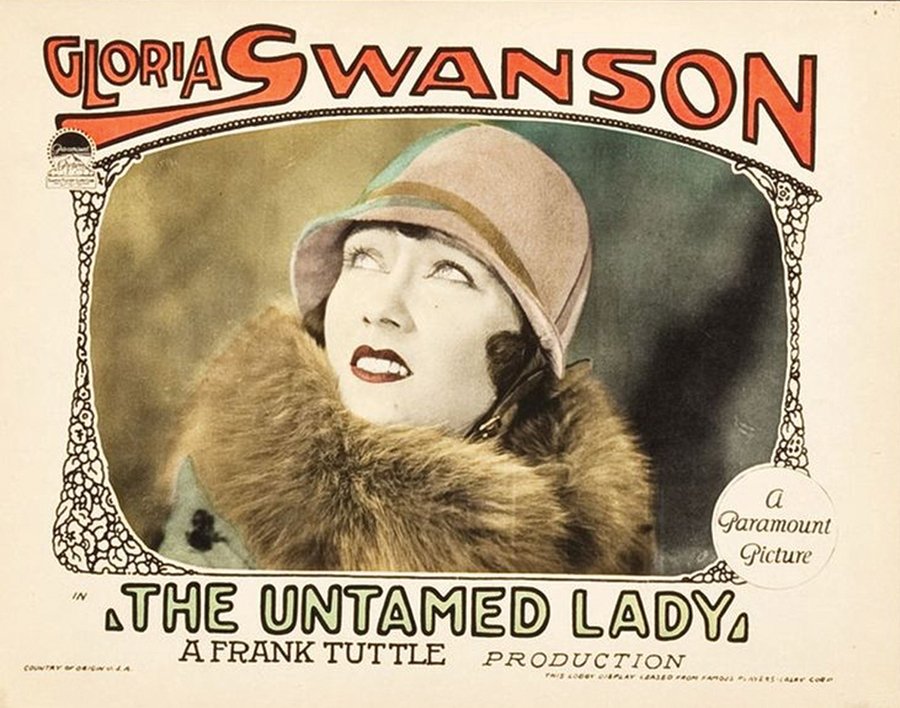

Preceding the glamorous couple was the film’s director, Frank Tuttle, who arrived on Monday, the 4th of January, and promptly scouted the area for potential scene locations. Better known in Hollywood circles as a writer, Tuttle had recently directed a handful of movies for Paramount, but had not previously directed Gloria Swanson. The 30-member Paramount troupe, along with Gloria’s co-star, Lawrence Gray, trailed Tuttle into town. On Thursday evening, an eight-piece band, which included legendary Pinehurst caddie Robert “Hardrock” Robinson, greeted Gloria and Henri upon their arrival at the Southern Pines railroad station platform. The stage was set for the shooting of the film eventually to be called The Untamed Lady.

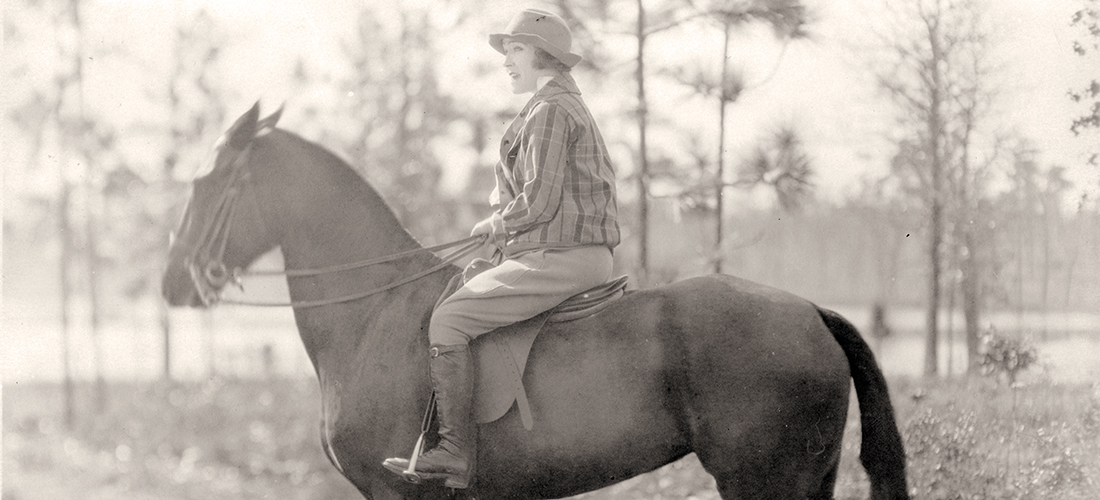

Swanson described the plot of the movie as a “story about a spoiled rich girl (St. Clair Van Tassel) who almost ruins her life with her willfulness but who is rescued before it is too late by a young man who truly loves her in spite of her faults.” The script called for scenarios involving car wrecks and gallops on horseback. Given that Swanson was an experienced horsewoman, Tuttle presumed he would have no need for a double for the heroine’s riding scenes.

Even Pinehurst golfers, who normally displayed scant interest in cinema, were intrigued by the arrival of Swanson and the Paramount production crew. The Pinehurst Outlook reported that even the best players had “changed their playing schedules in order to be thoroughly acquainted with the doings of the small movie company that has come to this resort.” And interest in the production extended well beyond the Sandhills. The Elizabeth City Daily Advance reported “scores flocked into the Carolina Hotel to get a glimpse of the famous screen actress. Parties of girls, all ‘Swanson fans’ drove in from High Point, ninety miles away . . . Charlotte and other nearby points sent their unofficial and curious delegations. All in all, Pinehurst seethed with an activity such as is common only in boom towns.”

Though Swanson may have appeared happy and carefree to her adoring fans, she was beset with turmoil regarding her future in filmmaking. Frustrated by what she deemed to be Paramount’s poor script selections as well as the heavy workload demanded of her by the studio, Swanson had decided the previous July not to renew her contract with the company. Instead, she had inked a new deal with United Artists (UA), where she anticipated that she, like fellow UA superstars Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, would have the freedom to choose scripts she liked. UA would also afford Swanson the opportunity to independently produce movies herself, and do so on a less demanding schedule. But before beginning her new association, she was contractually obligated to make two final movies for Paramount, the first of which was The Untamed Lady.

Swanson believed that Paramount intended to make as much money as it could in these last two films by stripping the production expenses to the bone with “no big directors, no expensive stories, (and) no large casts.” She was particularly displeased with the studio’s selection of Frank Tuttle as the director of The Untamed Lady, later suggesting that “out of insecurity . . . he (Tuttle) pretended to be utterly confident at all times, the dapper Ivy League type who always had the answer ready before the question was asked.” While Gloria was initially inclined to “breeze through” the filming without making any special effort, it occurred to her that she soon would be producing her own movies so, “if the studio was determined to throw me into rote parts . . . I would take all the extra energy I might have used in more demanding roles, and devote it in learning how to make pictures. In other words, I would turn Paramount into my producing school if I could.” And she did, redirecting scenes that Tuttle had already approved, making changes to the script, and consulting one-on-one with the crew’s technicians. Swanson would reflect that Tuttle (who would ultimately enjoy a successful directing career) may have come to regard her as “more willful than the girl in the script.” Nevertheless, Swanson considered the filmmaking knowledge gained during her two weeks in Pinehurst to have been invaluable preparation for the more active production role she undertook in later movies.

Tuttle chose the Sandhills Woman’s Exchange cabin as the location for one scene. McKenzie’s Pond (near what is now Juniper Lake Road) was selected for another in which the obstinate St. Clair Van Tassel insists on driving across an unsafe bridge in flagrant disregard of a warning sign. At the time, McKenzie’s Pond teemed with activity. Picnickers and folks out for a brisk walk enjoyed the serene atmosphere where farmers brought their grain to Jesse McKenzie’s mill, formerly known as Ray’s Mill. Within a decade of the filming of The Untamed Lady, the dam collapsed, and all vestiges of McKenzie’s Pond would disappear. Later the dilapidated remnants of the old mill burned to the ground. Today, visitors would be hard-pressed to envision the site’s once idyllic setting.

Not surprisingly, the marquise and marquis were feted during their stay in Pinehurst. Swanson and her husband were guests of honor at a dinner dance held at Pinehurst Country Club arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur N. Pierson Jr., of Westfield, N.J. Mr. and Mrs. Frank Tuttle, Mr. and Mrs. Richard Tufts, and Lawrence Gray were among the attendees. Charles Picquet, the general manager of Pinehurst’s Carolina Theatre, hosted the couple at the theater for a Friday evening affair. Gloria also made a splash at the Gun Club, which had invited members of the film troupe to take part in the club’s weekly shooting competition. Showing dead-eye proficiency, Swanson took home first prize among the female contestants.

The Sandhills had been chosen as a venue for the January filming with the belief that the location would be southerly enough to be snow-free. But on the eve of the climactic scene in which Gloria was to make a dash on horseback to a log cabin to warn Lawrence Gray’s character that the movie’s villain was in hot pursuit, snow blanketed Pinehurst. With a costly delay beckoning, Tuttle scrambled to find the nearest suitable snow-free location. He found one on Drowning Creek, 15 miles south of Pinehurst, complete with a log home called Mosagiel Cabin. The 3,000-acre site, which later became part of Camp Mackall, was then owned by local attorney J. Talbot Johnson. Tuttle made arrangements with Johnson for access to the property late on a Sunday night. By 9 a.m. the next morning, the crew, together with Gloria, her horse, and 10 Packard automobiles, had made the journey to Mosagiel Cabin. An hour later the day’s shooting began. The Pilot reported that Swanson soon was engaged in “riding the pine woods at more than the speed limit and tearing up the turf in the effort to rescue the unsuspecting fellow at the house.”

Then, after 10 minutes in the saddle, Swanson suddenly stopped the horse in its tracks. Dismounting, she walked it back to the corral and informed the nonplussed Tuttle that she could not go through with any further riding. She made no further explanation for her sudden decision, nor did Tuttle ask for one. In her autobiography, she explained that, “I had the clearest premonition of tragedy as I rode, a voiceless warning that I must never ride again. I knew that Henri’s father had died after a riding accident, but the feeling I had admitted of no logical connection. It was a command of terrifying force . . . I couldn’t dream of ignoring it. Moreover, I knew that nothing would induce me to ever ride again.” Swanson’s double completed the shooting.

The Carolina Hotel prepared sumptuous dinners for the film company at Mosagiel Cabin both Monday and Tuesday nights. At the conclusion of filming, a reception was held at the cabin where some of the locals savored the chance to chat with Swanson and the rest of the troupe. The Pilot reported the impression of one guest who gushed that “Gloria is a peach,” and that the cast was “chummy as if they were home folks.” Gloria was effusive in her flowery praise of the Sandhills. She expressed her love of Pinehurst, Mosagiel, the climate, the delicious atmosphere, the pine trees, the elegant pine straw carpets to ride over, and the wonderfully clean water.

After final editing was expeditiously completed, The Untamed Lady was set for release on March 22. The well-connected Charles Picquet finagled pre-release world premiere showings at the two Carolina Theatres, by having the film air-freighted from Los Angeles at the cost of $200. Two presentations were scheduled for March 17 in Pinehurst with two more scheduled the following day at the theater in Southern Pines. The Pilot reported that “probably one of the biggest crowds ever drawn by a single attraction came flocking into the two Carolina theatres” to attend the movie, and to see how the area’s familiar points appeared on the big screen. The report concluded that “the show was all right. The crowd was pretty near the whole population.”

But when the film made its grand opening the next week, reviews were tepid at best. The New York Times’ review described the film as “a sort of farfetched, modernized conception of The Taming of the Shrew, but as Miss Swanson does not look like a shrew, and never acts as if she really needed taming, one may gather that, taking it by and large, William Shakespeare’s play has somewhat the better of the film.” Gloria Swanson’s rueful observation that Paramount sought to punish her imminent departure with a substandard production may not have been far off the mark.

After completing an obligatory final movie for Paramount, Swanson plunged into her eagerly anticipated association with United Artists. For a while, she became something of an entrepreneurial trailblazer for women in cinema, employing the technical knowledge she acquired in Pinehurst to not only act in her films but produce them and assume the financial risks involved. She looked to Henri for advice, but the marquis’ skills did not really run in that direction. For the most part, Gloria was on her own. And though she now had a good working understanding of the filmmaking process, she had yet to learn how to control costs by keeping shooting on a tight schedule. By the star’s own admission, her first production effort took “nine months to make instead of six weeks.” Far over budget, The Loves of Sunya depleted an unhealthy portion of Swanson’s cash reserves.

Undaunted, she undertook the task of bringing Sadie Thompson to the screen. The story featured a puritanical minister attempting the reformation of Sadie — a prostitute (played by Swanson). Instead the minister falls in love. Swanson cleverly maneuvered the then controversial project past the objections of the censors, and made what was subsequently regarded as one of the best of the silent movies. Swanson felt that Sadie was a potential box office hit, but she harbored a concern that many theater owners might refuse to exhibit the film. If that happened, she could be financially ruined. To make matters worse, Sadie had run over budget and Swanson needed cash, both for her own needs and for financing her next picture.

So it was a beleaguered Swanson who met banker Joseph P. Kennedy (father of U.S. President John F. Kennedy) for lunch to seek financial assistance and advice. It was the start of a star-crossed relationship. After reviewing her finances, Kennedy informed Gloria that her affairs were a mess. He offered to take charge and restore order. Worn down by her debts, and impressed by Kennedy’s business acumen and take-charge persona, Gloria agreed. Before long Joe Kennedy had taken over Swanson’s entire life. He would urge her to sell her distribution rights to Sadie to get clear of her mounting debts. Despite misgivings, she did so. As she expected, the movie became a hit, and Gloria would regretfully watch as the buyer amassed large profits.

As Kennedy was making a concerted effort to wriggle his way into the film business himself, he cajoled Swanson into making a picture in a joint venture with his own fledgling operation, RKO Pictures. Kennedy insisted that the talented Erich von Stroheim direct the movie. But Von Stroheim was notorious for causing interminable delays and that unfortunately occurred on their project, Queen Kelly. Saddled with staggering overruns, the movie was never released in the U.S., though a modified version was shown in Europe. Swanson’s reliance on Kennedy’s judgment as a movie mogul seemed misplaced.

To complicate matters, the two had become lovers. Gloria would later write that though she enjoyed a happy marriage with Henri, she “knew perfectly well that whatever adjustments or deceits must inevitably follow, the strange man beside me, more than my husband, owned me.” Kennedy managed to lure Henri away from Gloria’s side by hiring him to fill a position in Paris as European director for Pathé Studios.

The Swanson-Kennedy film collaboration coincided with the advent of “talkies.” Many silent movie stars were unable to make the transition to sound, but Swanson possessed a clear and pleasing voice and had little difficulty. Her first talking picture, The Trespasser, was a major success, but a second effort was less so. Her professional and personal relationship with Kennedy came to an abrupt end after Gloria questioned Joe’s attribution of certain expenses connected to Gloria’s individual account. The end of their affair came too late to salvage Swanson’s marriage to the marquis and the two divorced.

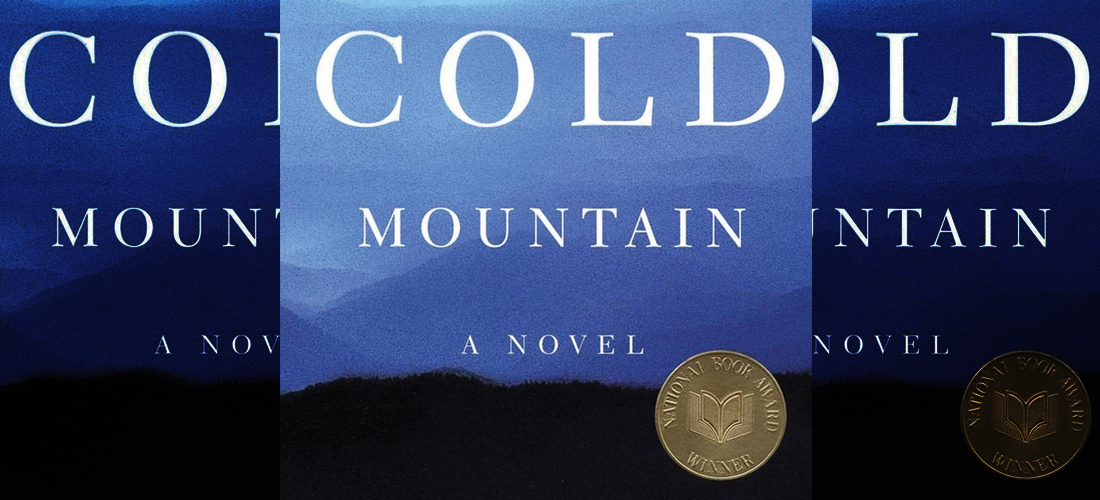

Swanson continued to acquire husbands and make movies thereafter, but her star definitely waned as she entered her 30s and the moviegoing public’s tastes changed. By 1949, she was reconciled to the fact that she would never make another movie, having been off the screen altogether for over eight years. But then director Billy Wilder cast the 50-year-old actress as a faded silent motion picture star who dreams of a comeback in Sunset Boulevard. Swanson’s knowing, on-the-mark performance won an Oscar nomination and capped a remarkable comeback that the character she played — the delusional Norma Desmond — failed to achieve. Today, Sunset Boulevard is regarded as one of the all-time film noir classics.

Swanson considered most of the roles offered her after Sunset Boulevard to constitute pale imitations of her Norma Desmond character, and she turned them down. She made only three films thereafter, though she performed often on stage and in television productions. She busied herself as a nutritional advocate, writing her autobiography, and painting and sculpting. She died in 1983 at age 84.

But what became of the film of The Untamed Lady? Like those who had attended the picture’s March, 1926 sneak preview at the two Carolina Theatres, I had hoped to view how McKenzie’s Pond, the Sandhills Woman’s Exchange cabin and Mosagiel Cabin appeared on screen. However, as is the case with many of the old silent movies, no reels of the film are known to presently exist. In the early days of filmmaking, a studio rarely retained a movie in its library unless someone in charge felt there was a prospect the film might be rereleased in the future. Often, the last exhibitor in a run was not even asked to return the movie to the studio.

“There was no market for a film after its theatrical run,” explains Todd Berliner, professor of film studies at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. “Studios made a practice of retaining their movies only after television and video became potential ancillary markets, allowing the studios to reap benefit from an existing film.”

The Film Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded by Martin Scorsese and dedicated to film preservation, estimates that 90 percent of American films made before 1929 are lost. The Library of Congress believes that 75 percent of all silent films are lost forever. Nonetheless, there remains a slim chance that The Untamed Lady could turn up one day. In 1978, a cache of silent movie reels was discovered beneath an ice rink in the Yukon. The films were in good condition having been protected by the permafrost from decomposition.

Today North Carolina is no stranger to the cinema. The Color Purple, The Last of the Mohicans, Dirty Dancing and Talladega Nights were all filmed here by major studios. But Paramount’s production of The Untamed Lady stands as Hollywood’s first feature film shot on location in the Tar Heel State. So it was that North Carolina’s film debut and the Golden Age’s greatest female movie star joined to captivate the Sandhills for a fortnight. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.