SIMPLE LIFE

The Light in August

Catch it before it fades

By Jim Dodson

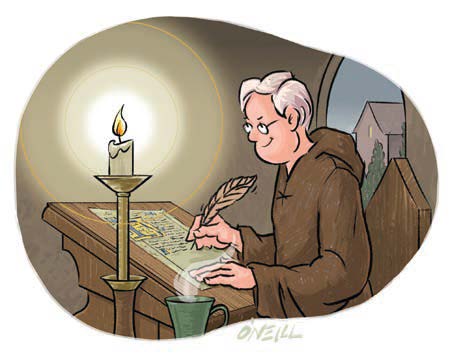

Most mornings before I begin writing (often in the dark before sunrise), I light a candle that sits on my desk.

Somehow, this small daily act of creating a wee flame gives me a sense of setting the day in motion and being “away” from the madding world before it wakes. I sometimes feel like a monk scribbling in a cave.

It could also be a divine hangover from early years spent serving as an acolyte at church, where I relished lighting the tapers amid the mingling scents of candle wax, furniture polish and old hymnals, a smell that I associated with people of faith in a world that forever hovered above the abyss.

According to one credible source, the word “light” is used more than 500 times in the Bible, throughout both Old and New Testaments. On day one of creation, according to Genesis, God “let there be light” and followed up His artistry on day four by introducing darkness, giving light even greater meaning. The Book of Isaiah talks about a savior being a “light unto the gentiles to bring salvation to the ends of the world.” Throughout the New Testament, Jesus is called the “Light of the world.”

But spiritual light is not exclusive to Christianity. In the Torah, light is the first thing God creates, meant to symbolize knowledge, enlightenment and God’s presence in the world. Surah 24 of the Quran, meanwhile, a lyrical stanza known as the “Verse of Light,” declares that God is the light of the heavens and the Earth, revealed like a glass lamp shining in the darkness, “illuminating the moon and stars.”

Religious symbolism aside, light is something most of us probably take for granted until we are stopped in our tracks, captivated by the stunning light show of a magnificent sunrise or sunset, a brief and ephemeral painting that vanishes before our eyes.

Sunlight makes sight possible, produces an endless supply of solar energy and can even kill a range of bacteria, including those that cause tetanus, anthrax and tuberculosis. A study from 2018 indicated rooms where sunlight enters throughout the day are significantly freer of germs than rooms kept in darkness.

The intense midday light of summer, on the other hand, is something I’ve never quite come to terms with. Many decades ago, during my first trip to Europe, I was fascinated (and quite pleased, to be honest) to discover that, in most Mediterranean countries, the blazing noonday sun brings life to a near standstill. Shops close and folks retreat to cooler quarters in order to rest, nap or pause for a midday meal of cheese and chilled fruit. I remember stepping into a zinc bar in Seville around noon and finding half the city’s cab drivers hunkered along the bar. The other half, I was informed, were catching z’s in their cabs in shaded alleyways. The city was at a complete, sun-mused halt.

The Spanish ritual of afternoon siesta seems entirely sensible to me (a confirmed post-lunch nap-taker) and is proof of Noel Coward’s timely admonition that “only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.” Spend a late summer week along the Costa del Sol and you can’t avoid running into partying Brits on holiday, most as red as boiled lobsters from too much sun.

In his raw and gothic 1932 novel, Light in August, a study of lost souls and violent individuals in a Depression-era Southern town, William Faulkner employs the imagery of light to illuminate marginalized people struggling to find both meaning and acceptance in the rigid fundamentalism of the Jim Crow South.

For years, critics have debated the title of the book, with most assuming it is a direct reference to a house fire at the story’s center.

The author begged to differ, however, finally clearing up the mystery: “In August in Mississippi,” he wrote, “there’s a few days somewhere about the middle of the month when suddenly there’s a foretaste of fall, it’s cool, there’s a lambence, a soft, a luminous quality to the light, as though it came not from just today but from back in the old classic times. It might have fauns and satyrs and the gods and — from Greece, from Olympus in it somewhere. It lasts just for a day or two, then it’s gone . . . the title reminded me of that time, of a luminosity older than our Christian civilization.”

I read Light in August in college and, frankly, didn’t much care for it, probably because, when it comes to Southern “lit” (a word that means illumination of a different sort), I’m far more attuned to the works of Reynolds Price and Walker Percy than those of the Sage of Yoknapatawpha County. By contrast, a wonderful book of recent vintage, Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, tells the moving story of a blind, French girl and young, German soldier whose starstruck paths cross in the brutality of World War II’s final days, a poignant tale shot through with images of metaphorical light in a world consumed by darkness.

But I think I understand what Faulkner was getting at. Somewhere about middle-way through August, as the long, hot hours of summer begin to slowly wane, sunlight takes a gentler slant on the landscape and thins out a bit, presaging summer’s end.

I witnessed this phenomenon powerfully during the two decades we lived on a forested coastal hill in Maine, where summers are generally brief and cool affairs, but also prone to punishing mid-season droughts. Many was the July day that I stood watering my parched garden, shaking my cosmic gardener’s fist at the stingy gods of the heavens, having given up simple prayers for rain.

On the plus side, almost overnight come mid-August, the temperatures turned noticeably cooler, often preceding a rainstorm that broke the drought.

When summer invariably turns off the spigot here in our neck of the Carolina woods, sometime around late June or early July, I still perform a mental tribal rain dance, hoping to conjure afternoon thunderstorms that boil up out of nowhere and dump enough rain to leave the ground briefly refreshed.

I’ve been fascinated by summer thunderstorms since I was a kid living in several small towns during my dad’s newspaper odyssey through the deep South. Under a dome of intense summer heat and sunlight, where “men’s collars wilted before nine in the morning” and “ladies bathed before noon,” to borrow Harper Lee’s famous description of mythical Maycomb, I learned to keep a sharp eye and ear out for darkening skies and the rumble of distant thunder.

I still gravitate to the porch whenever a thunderstorm looms, marveling at the power of nature to remind us of man’s puny place on this great, big, blue planet.

Such storms often leave glorious rainbows in their wake, supposedly a sign (as I long-ago learned in summer Bible School) of God’s promise to never again destroy the world with floods.

Science, meanwhile, explains that rainbows are produced when sunlight strikes raindrops at a precise angle, refracting a spectrum of primary colors.

Whichever reasoning you prefer, rainbows are pretty darn magical.

As the thinning light of August and the candle flame on my desk serve to remind me, the passing days of summer and its rainbows are ephemeral gifts that should awaken us to beauty and gratitude before they disappear.