SIMPLE LIFE

Worrying and Watering

For love of gardens and democracies

By Jim Dodson

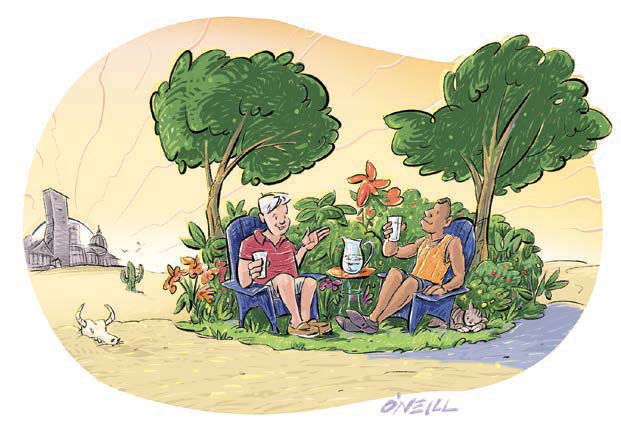

A neighbor who walks by my house each evening like clockwork sees me sitting under the trees with a pitcher of ice water and walks over to say hello.

I invite Roger to take a seat and have a cold drink.

“It’s tough to keep moving in this heat,” he explains, sitting down. “It’s something, isn’t it? But your garden looks great.

How do you keep it so nice and green?”

“A lot of worrying and watering,” I say. “Sometimes you have to make tough choices.”

In one of the hottest and driest summers in memory, I’d decided to let my yard turn brown in favor of keeping flowering shrubs and young trees watered and green. As the late famous British landscape designer named Mirabel Osler once said to me over her afternoon gin and tonic, landscape gardening is a ruthless business, especially in a drought. Grass will eventually return, but no such luck with a shriveled shrub or a dead young tree.

“September brings relief, rain and second blooms,” I add. “I’m already in a September state of mind.”

He smiles and nods.

“Hey,” he says casually, “let me ask you something.”

I expect another question about the garden. Like the best time of the day to water your shrubs, or when it’s safe to fertilize or prune azaleas.

But it isn’t even close.

“I’m worried about America. People seem so angry these days. Why do you think Americans hate each other?”

The question takes me by surprise. I could give him a few thoughts on the subject: the woeful decline of fact-based journalism, an internet teeming with conspiracy peddlers, politicians who feed on polarization, the unholy marriage of politics and religion, and the sad absence of civility in everyday life.

Instead, I tell him a little story of rebirth.

In the spring of 1983, I telephoned my dad from the office of Vice President George Bush and told him that I no longer wanted to be a journalist. For almost seven years, I’d worked as a staff writer of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Sunday Magazine, covering everything from presidential politics to murder and mayhem across the deep South. As a result of my work, I’d been offered my dream job in Washington, D.C., but found myself suddenly fed up with writing about crooks, con men and politicians. Bush, however, was an exception. We’d traveled extensively together during the 1980 campaign and had wonderful conversations about life, family and our shared love of everything from American history to golf. During our travels, Bush invited me to drop by his office anytime I happened to be in the nation’s capital. Unfortunately, he was traveling the day I turned down my dream job in Washington, but his secretary allowed me to use her phone. So, I called my dad and told him I planned to move to New England and learn to fly-fish.

“When was the last time you played golf?” he calmly asked.

“I think Jimmy Carter had just been elected.”

He suggested that I meet him in Raleigh the next morning.

So, I changed my flight and there he was, waiting with my dusty Haig Ultra golf clubs in his back seat. We drove to Pinehurst, played famed course No. 2 and finished on the Donald Ross porch, talking about my early midlife career crisis over a couple of beers. I’d just turned 30.

I told him that I “hated” making a living by writing about the sorrows of others, especially when it came to the increasingly shallow and mean-spirited world of politics.

“You may laugh, but here’s a thought,” the old man came back, sipping his beer. “Before you give up journalism, have you ever considered writing about things you love rather than things you don’t?”

Sadly, I did laugh. But he planted a seed in my head. A short time later, I resigned from my job in Atlanta and wound up on a trout river in Vermont, where I learned to fly-fish, started attending an old Episcopal Church and knocked the rust off my dormant golf game at an old nine-hole course where Rudyard Kipling played when he lived in the area.

I soon went to work for Yankee Magazine and spent the next decade writing about things I did love: American history, nature, boat builders, gardeners and artists — a host of dreamers and eccentrics who enriched life with their positive visions and talents.

I also got married and built my first garden on a forest hilltop near the Maine coast.

“I never looked back,” I tell Roger. “I’ve built five gardens since.”

Roger smiles.

“So, you’re telling me we all need to become gardeners?”

“Not a bad idea. Gardeners are some of the most generous people on Earth. We make good neighbors. Most of the country’s founders, by the way, were serious gardeners.”

I pour myself a little more ice water and tell him I’ve learned that gardens and democracies are a lot alike. “Both depend on the love and attention we give them. Especially in difficult times like these.”

Roger finishes his drink and stands up. “That’s something to think about. Here’s to September, cool weather and good neighbors,” he says. “Maybe by then even your grass will be green again.”