Almanac

The wonder of champion trees

Story and Photographs by Todd Pusser

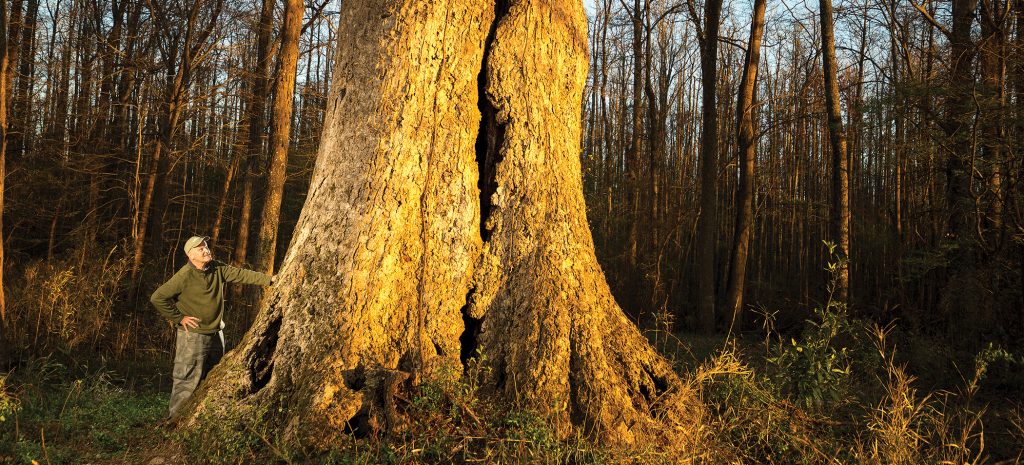

This and above photograph: Gary Williamson and National Champion Tulip Poplar in Chesapeake, VA

It was a tip from a local hunter that first alerted Gary Williamson to the presence of the tree. Standing near the edge of a plowed field, just across the North Carolina line in Chesapeake, Virginia, the tulip poplar dwarfs all other trees nearby. Well over 100 feet tall and 32 feet in circumference, it is the largest of its kind anywhere in the United States.

The tree, while alive and healthy, is hollow on the inside, making it impossible to accurately age. Tulip poplars can live for several hundred years, and it is likely this giant was alive long before the United States declared its independence from Great Britain. Once, while leading a field trip of big tree enthusiasts, Williamson managed to crowd 15 people inside the tree at one time with room to spare. The tree is a survivor, having lived through droughts, wars, hurricanes, and the unrelenting pressure of the saw blade.

Mankind has long been fascinated by trees, especially large trees. The fascination reached a fever pitch in the early 1800s when explorers, searching for gold in California, reported the first encounters with coastal redwoods and giant sequoias, those blue whales of the plant kingdom. Reaching heights of over 350 feet, with diameters well north of 19 feet, these gargantuan trees are the largest living organisms on Earth. It has been estimated that one particular giant sequoia, appropriately nicknamed “The President,” holds over 2 billion leaves among its branches.

National Champion Darlington Oak Tree in Edgecomb County, NC

When Europeans first colonized America, they set about the task of felling the continent’s vast virgin forests with axes and handsaws, using the wood to make houses, barns, ship hulls and railroad ties. The advent of steam-powered logging machinery, followed later by gas-powered chainsaws, served to increase the efficiency of logging, and by the mid-20th century, virtually no acre of forest in the United States remained untouched by the saw blade.

Around this time, in the early 1940s, the American Forestry Association (now called American Forests) created The National Register of Champion Trees to encourage members of the general public to find, document and preserve the largest remaining specimens of this continent’s (approximately) 750 species of trees. The program (www.americanforests.org) created a unique scoring system to help determine if a tree qualifies as a champion.

The formula is straightforward: Take the circumference of the tree (in inches) at breast height, add the height of the tree (in feet), and then add one-quarter of the average crown spread (in feet) for a total point score. The program is active in all 50 states as well as American territories like Puerto Rico. Each state maintains its own list of the largest trees found within its borders, crowning them state champions. If a state champion tree proves exceptionally large, it may qualify for the Register as a national champion.

Anyone can nominate a tree for the National Register. There is no need to be a botanist, forester or professional arborist. All it takes is a keen eye and a sense of curiosity for the natural world.

Few people have nominated as many champion trees to the National Register as Virginia natives Gary Williamson and Byron Carmean. For the past four decades, both men (each in their mid-70s) have traversed the backwoods of North Carolina and Virginia, searching for superlative trees. Most weekends will find them kayaking rivers, walking floodplain forests, driving remote backroads, and searching old cemeteries and estates for the next champion.

State Champion Flowering Dogwood in cemetary in Clinton, NC

In that time, the pair have nominated some truly extraordinary trees. Among them are North Carolina’s largest tree, a rotund bald cypress (with a total score of 558 points) growing along the Roanoke River in Martin County; the national champion Darlington oak tree (which stands alone in a farmer’s field near Rocky Mount); the national champion silky camellia, whose broad, fragrant flowers brighten up the springtime forest in Merchants Millpond State Park; a state champion Hercules club (an unusual looking tree covered in large thorns) in the town of Duck in the Outer Banks, and a state champ Shumard Oak growing along the nutrient rich soils of the Deep River. Over 142 feet tall, with an average crown spread of 110 feet, the oak can easily be seen on Google Earth.

I recently joined Williamson on a cool winter’s day to see and photograph the national champ tulip poplar growing in Chesapeake. Bearing similarities to European poplars and having white, tulip-shaped flowers gives the tree its common name. However, the tulip poplar is in no way related to poplars or tulips. Instead, it’s a member of the magnolia family and is the tallest hardwood tree in North America.

Taking pictures of a champion tree is inherently difficult. There is simply no way to sufficiently capture the essence of “bigness,” that wow factor, within a two-dimensional frame. No matter what lens is used or at which angle you shoot, the resulting image will inevitably diminish the size of the tree. Nevertheless, I persisted for well over an hour, posing Williamson at various positions around its trunk and even inside the tree.

Finally, as the sun was sinking below the horizon, I stopped taking photos and simply stood at the base of the living monarch, staring up toward its immense crown. Running my hands over its furrowed bark, I thought of what the forests looked like at the time my ancestors first set foot on this continent. Here, standing before me, was a shining example of that bygone era and one of the true wonders of the natural world. PS

Naturalist and photographer Todd Pusser grew up in Eagle Springs. He works to document the extraordinary diversity of life both near and far. His images can be found at www.ToddPusser.com.