It Slices. It Dices.

Memoir by Stephen E. Smith • Illustration by Harry Blair

“Get up! Get up! Get up, up, up!” my mother blurted.

It was at 6:30 a.m., the first day of Christmas break, and as always she felt compelled to rouse her children at the most ungodly hour. I lifted my head from the pillow and stared bleary-eyed at her figure in the bedroom doorway. Wrapped to her chin in a blue terrycloth robe, her fists were planted firmly on her hips. She meant business. “You’re to march yourself down to the Safeway and ask Mr. Short if he’ll give you a job for the holidays,” she ordered. “You can earn enough money to pay for your books next semester. And next time I see Mr. Short, I’ll find out if you asked him for a job.”

“Can’t you even say, ‘Welcome home’?” I asked.

“Sure. Welcome home, Mr. Big Shot College Guy. Now get out of that bed and get yourself down to the Safeway.”

I was suffering from severe sleep deprivation. I’d caught an all-night ride home from North Carolina and had dragged into the house on Janice Drive at 3:15 a.m. But my mother was not to be denied, so I managed to pull on the wrinkled clothes I’d worn the day before and stumbled downstairs to eat a bowl of my brother’s Froot Loops. At 8:30 a.m. I scuffled up Bayridge Avenue to the Eastport Shopping Center, where I found Mr. Short on the dock, supervising the unloading of pallets of dog food from a tractor-trailer. He shook my hand and asked how college was going.

“It’s fine,” I answered. “I was hoping you might have an opening for a cashier during the holidays. I’m not looking to work eight hours a day, but, you know, something part time.”

“If I had an opening, I’d hire you,” he said. “But right now I have all the cashiers I need. I’d have to cut someone else’s hours, and that wouldn’t be fair, especially at Christmas.” My spirits soared. If he didn’t have an opening, I could pass the holidays stretched out on my bed reading P.G. Wodehouse.

“I’ll tell you what,” he continued, “I’ve got a friend who’s the manager at the Drug Fair in Parole. Go see him and tell him I sent you. He’s looking for holiday help.”

A job at Drug Fair was the last thing I wanted, but I had to make an inquiry. My mother was as good as her word, and I knew she’d buttonhole Mr. Short the next time she visited the Safeway. If she found out I hadn’t applied for the Drug Fair job, she’d make my Christmas break miserable, which she had already begun to do by wakening me before sunup.

Among cashiers, there existed a hierarchy, and working a register at Safeway carried with it a degree of status and a wage that was at least $1.75 an hour. Drug Fair was a discount pharmacy, emporium and grocery store, a low-rent warehouse for plastic crap and wilted vegetables, where the discount prices were clearly marked on each item — work for the dimwitted — and the pay was $1.25 an hour.

I caught the bus to Parole and found the Drug Fair manager, a rumpled, balding, ectomorphic fellow with thick wire spectacles and a long pointy nose, puzzling over paperwork in an elevated office that overlooked a line of disheveled employees who were pounding away at their cash registers. He appeared to be in emotional distress, his mouth screwed into a grotesque snarl.

“Excuse me,” I said. He looked up, snatched the glasses from his face and tossed them on the countertop in a display of frustration. “Mr. Short over at Safeway said I should talk with you about working as a cashier for the holidays. I don’t need a full-time job, just some part-time work if you’ve got it.”

Sweet relief swept over his face, his lips stretching into a half smile. “Mr. Short sent you?” he asked.

“He said you might need an experienced cashier.”

“You used to work at the Safeway?”

“For two years, until I went off to college.”

He grinned fully. I was apparently the man he’d been waiting for. He stepped out of his office, planted both feet flat on the linoleum and looked me up and down. “Can you work a register?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“And you’ve worked stock?”

“Yes, sir.”

My God, he was going to hire me! I was going to pass the next two weeks checking out Christmas junk at the Drug Fair for minimum wage! This was not good.

The manager handed me a pen and an application clamped to a clipboard, and I took a couple of minutes to fill in the information.

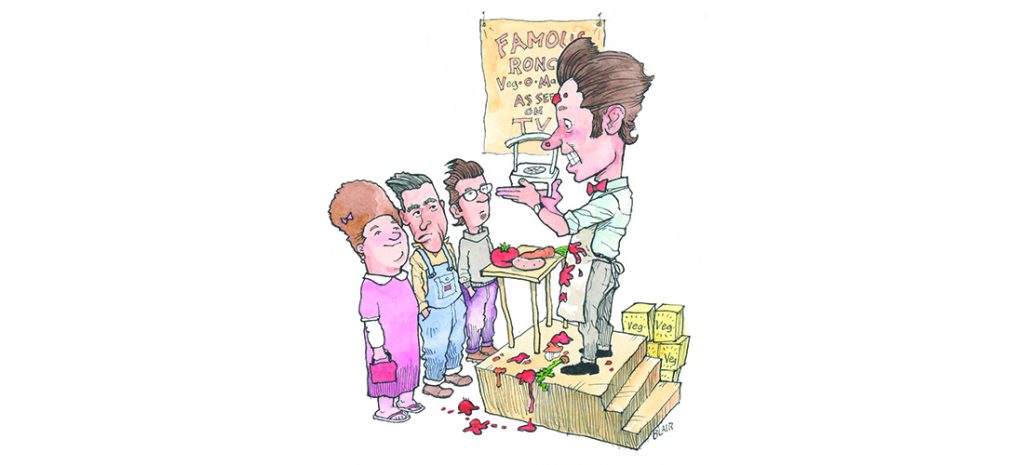

“Follow me,” he said, and we walked quickly down aisle four toward the back of the crowded store. “I can use you to relieve my regular cashiers for their lunch and supper breaks, and you can help keep the shelves stocked, especially this display. We’re selling the hell out of these things.” He pointed to a chest-high pyramid of black, orange and beige boxes crowned with an unboxed white plastic kitchen device known to every American who owned a TV. “We’ve had to restock this display three times this morning. You know anything about Veg-O-Matics?” he asked.

What happened next was probably brought on by fatigue — or maybe I needed an excuse to get fired before I got hired. Whatever the cause, a synaptic misfire propelled me into the past. I picked up the display device, held it out in front of me and began to deliver the requisite spiel:

“Imagine slicing a whole potato into uniform slices with one motion. Bulk cheese costs less. Look how easy Veg-O-Matic makes many slices at once. Imagine slicing all these radishes in seconds. This is the only appliance in the world that slices whole firm tomatoes in one stroke with every seed in place. Hamburger lovers, feed whole onions into Veg-O-Matic and make these tempting thin slices. Simply turn the dial and change from thin to thick slices. You can slice a whole can of prepared meat at one time. Isn’t that amazing? Like magic, change from slicing to dicing. That’s right, it slices, it dices, it juliennes, perfect every time!”

By the time I’d finished yammering, the manager’s eyes were wide and his jaw slack.

“How’d you learn that?” he asked.

“I used to watch the commercial on TV, and it just sort of stuck in my head.”

My fascination with the Veg-O-Matic stretched back to my junior year in high school. Strung out on testosterone and teenage angst, I suffered insomnia for about six months. On those long, restless nights, I’d roll out of bed after everyone else in the house was asleep, slink down to the “rec” room and turn on the black and white TV. WJZ, the local CBS affiliate, was the only station out of Baltimore that aired anything other than an Indian Chief test pattern in the early a.m., so I’d tune in channel 13 in time to catch Father Callahan of St. Francis Xavier House of Prayer bestowing his benediction. Then I’d settle in for a three-hour run of continuous raise-your-own-chinchillas commercials.

My clandestine obsession with Father Callahan and chinchillas continued for two or three months — until the fateful night when the good Father delivered his usual homily and the chinchilla commercials failed to materialize. Instead, a plastic guillotine-like device appeared on the TV screen, contrasted against a background map of the world, below which were printed the words “World Famous Veg-O-Matic.” Then a disembodied voice said: “Imagine slicing a whole potato into uniform slices with one motion. Bulk cheese costs less. Look how easy Veg-O-Matic makes many slices at once. . . . ”

I’d spent my Father Callahan/chinchilla nights dozing fitfully on the couch and sneaking back to my room before the rest of the family awakened, but on that memorable evening — I’ve come to think of it as Night of the Veg-O-Matic — I sat there stupefied, watching the commercial over and over. I couldn’t take my eyes off the screen, and by morning I had the narration memorized — every nuance, modulation and inflection — to which I could add hand gestures, including the graceful, upturned palm that beckoned, “Buy me, buy me, buy me. . . .”

Later that day, I was eating lunch in the high school cafeteria with my regular buds when freckle-faced Ronnie Wheeler produced a sliced tomato his mother had wrapped in wax paper to keep it from saturating the white bread he needed to construct his BLT. I jumped up, grabbed the tomato slices and ran through the entire Veg-O-Matic routine, spreading the segments across the Formica tabletop and finishing with the obligatory “. . . perfect every time!”

My friends were speechless, especially Ronnie, whose sandwich was ruined. They stared blankly before bursting into hysterics. The vice-principal, Mr. Wetherhold, a stern disciplinarian who abhorred any form of frivolity, hurried over to our table to discern the source of the disturbance. “What’s going on here?” he asked sternly.

“Do it!” my friends begged. “Do the Veg-O-Matic thing!” They didn’t have to ask twice. When I finished my second run-through, it was Mr. Wetherhold who was howling with laughter. Suffice it to say I spent a good deal of my time in high school doing “the Veg-O-Matic thing” for my friends. They never tired of it.

Now the Drug Fair manager’s face glowed with approval, and I could see that he’d suffered an epiphany. He rushed into the stockroom and reappeared with a folding table. He extended the legs, positioned the table in front of the pyramid of boxes and covered the top with a square of red cheesecloth. He grabbed an onion from the produce aisle, peeled away the skin, and ordered me to deliver my recitation again, this time with the unboxed Veg-O-Matic at my fingertips.

Despite my long and intimate history with the kitchen device, this was the first time I’d worked with one. But I muddled through the presentation by recalling the images I’d watched hundreds of times on TV, each motion transmitted from memory to physical articulation. I made quick work of the onion, repeating the entire monologue. My demonstration, although clumsy, went well enough to instantly earn me the title: 1965 Parole Drug Fair Veg-O-Matic Man.

“You’re hired!” the manager said. “I want you to do a demonstration at the top of every hour. Use all the tomatoes and onions you want, but stay away from the cheese and Spam. That stuff costs money.”

“Yes, sir,” I said dutifully.

“The rest of the time you can restock these Veg-O-Matics and relieve the cashiers who are going on break. Can you start tomorrow?”

“Yeah,” I said, “I guess.”

“Be here at 8 o’clock, and wear a white shirt.”

Crestfallen, I dragged myself into the parking lot and caught the bus back to Eastport. When I stumbled into our living room, it was 11:30 a.m., and I was whipped.

“Did Mr. Short hire you?” my mother yelled from the kitchen.

“He didn’t have any openings, but I got a job at Drug Fair in Parole.”

“Excellent,” she said.

When I turned up at Drug Fair on Saturday morning ready to begin my new career, the manager had anticipated my every need. The folding table was set up in aisle four, which was stocked with kitchen junk — Melmac dishes, spatulas, plastic forks, spoons and knives, etc. — and beside the table waited a freshly replenished pyramid of multicolored boxes containing the Veg-O-Matics. The tabletop was covered with the red cheesecloth from the day before, and a white apron of the style that loops around the neck and ties in the back was folded neatly on the table. An unopened can of Spam and a brick of Kraft Velveeta cheese were stacked beside the gleaming white Veg-O-Matic display model I’d used in my earlier demonstration, and a bag of assorted vegetables — tomatoes, onions, carrots and potatoes — awaited their fate. As a touch of class, the manager had placed a roll of paper towels on the table, and a beige commercial dome-topped trash can sat directly behind my workspace.

“Here, wear this,” he said, handing me a handsome black clip-on bowtie. I donned my apron and attached the bowtie to the wrinkled collar of my white shirt. “Now show me your stuff. Just use vegetables. The Spam and cheese are for show.”

I launched into my Veg-O-Matic dance at a measured pace, slicing up a small potato and allowing my hands to gracefully execute a lilting swirl at the conclusion of the shtick.

“That was even better than yesterday,” the manager beamed, “although I’d take it a little slower if I were you.” He looked up and down aisle four. “I’ll make an announcement at the top of every hour. You get yourself set up. Sell the hell out of these Veg-O-Matics. If you don’t, you’ll be in a checkout stand all day.” And he left me on my own.

I peeled an onion, and trimmed it to the proper size and shape. I was ready. Or as ready as I was ever going to be.

“We are pleased to direct your attention to aisle four,” I heard the manager announce over the PA system, “where you can view a demonstration of the miracle Veg-O-Matic, the 20th century’s greatest kitchen appliance. It makes an economical and useful Christmas gift! Do all your Christmas shopping in five minutes and have your Veg-O-Matics gift wrapped right here in the store. Christmas cards are available on aisle six.”

After my first two demonstrations, I discovered that operating the Veg-O-Matic wasn’t quite the effortless exercise I’d observed on TV. I directed my attention to the tomato, which I positioned perfectly between the upper and lower blades. “This is the only appliance in the world that slices whole firm tomatoes in one stroke with every seed in place,” I said, as I slammed down the top of the Veg-O-Matic. The tomato exploded like a water balloon, splattering juice and seeds all over my apron and the tabletop. The two customers who had gathered for my demonstration jumped back and bolted for the exit.

I’d created a huge mess. I mopped the tomato slop off my hands with a paper towel and brushed the seeds from my apron, but pulp continued to dribble from the bottom of the Veg-O-Matic, and I had to retreat to the stockroom to wash the blades. So tomatoes were out. Ripe ones, at least. After mopping the splatter from the tabletop, I attempted to slice an onion I’d peeled earlier. I gave a forceful downward thrust and the device worked perfectly, sending a cascade of onion slivers onto the cheesecloth. Still, it was a messy business; pieces of onion got stuck in the blades and had to be pried out. I had the same experience with carrots, stubborn chunks of which had to be worked free with my fingertips.

I settled, finally, on a peeled Idaho Russet potato. I cut the spud into four pieces, which I fed individually into the chopper. And the device worked as intended — neat and clean. The Veg-O-Matic was, after all, meant to transform a time-consuming, chaotic operation into a simple, wholesome procedure. And that’s what it did.

The secret, as with many physical actions, was in the wrist. It was all finesse. I’d place a piece of potato on the bottom blades and apply a sharp downward whack with the top. And voila! the potato was julienned, perfect for hash browns. If I spoke slowly, worked methodically and was meticulous with my cleanup, I could kill the better part of a half hour on each demonstration, thus allowing for only 30 minutes of working at a cash register before my next demonstration.

At first, I was worried that I wouldn’t sell enough Veg-O-Matics to keep my new job, but the pile of boxes diminished at an ever-increasing rate as Christmas approached and the manager was a happy man. I’d sold six to eight Veg-O-Matics with each demonstration, and I noticed that many customers who didn’t make an immediate purchase returned later to snatch up two or three Veg-O-Matics, having chosen convenience over thoughtful reflection. Usually these return customers felt compelled to offer an explanation for their delayed purchase. “You know,” they’d say, “I was thinking about your demonstration, and you’re right, this will make an excellent gift for my mother.”

Every day I’d work straight through until 10 p.m., taking an hour each for lunch and dinner, and then I’d catch the bus home in the dark. I’d shower and collapse into my bed to read for a few seconds in Pigs Have Wings, my latest Wodehouse novel, before falling asleep.

And that’s how it went for seven straight days. I’d turn up at Drug Fair at 8 a.m., an hour before the store opened, to prepare the potatoes for my demonstration. I’d restock the Veg-O-Matic display, piling the boxes high in an ergonomically conical construct of my own contrivance, and check out a register tray so that I could relieve cashiers who went on break.

If my schedule was exhausting, it also had its advantages. I slept like a stone, and the days flew by. At home, I didn’t have a conversation with my mother, father or sister that lasted more than 10 seconds. “Hi, how ya doing?” was as intimate as it got, which suited me. My father was asleep when I left in the morning and when I came in at night, I didn’t have to listen to my mother and sister bicker. Only my brother Mike, with whom I shared a room, was around when I staggered in whacked out from 12 hours of working with the public. He’d fill me in on the day’s drama with my sister, which made me glad I’d be headed back to college soon.

When the store closed at 9 p.m. on Christmas Eve, I used my humongous 5 percent employee discount to purchase gifts for the family — a cheap cotton bathrobe for my mother, which turned out to fit her like a circus tent, a simulated leather wallet for my father, a 45 of Donovan’s “Catch the Wind” for my brother, and the Beatles’ Help! for my sister. I was headed out the door with my packages when the manager stopped me.

“You’ve done a good job,” he said, a genuine smile on his pasty face. “And I’m hoping you’ll consider coming back to work through New Year’s Eve. You won’t be selling Veg-O-Matics, but I need experienced help to run the registers and handle returns. I could use you for at least 12 hours a day.”

Normally I would have responded with an emphatic “No,” but fresh in my memory were the money problems I’d experienced during my first four months at college and the hours I spent in McEwen Dining Hall scraping greasy dishes and scrubbing pots. With my paltry allowance, there was no hope of establishing a relationship with any of the girls I found myself drooling over as they roamed the campus. It was essential I screw up my courage and get myself an on-campus date. I’d have to double with an upperclassman who had a car, and to make that happen, I needed enough money to cover my share of the gas.

“All right,” I answered. “Can I get some overtime?”

“I’ll give you all the overtime you want. You can work 14 hours a day if you skip lunch and dinner.”

“All right,” I answered, “I’ll be glad to help out.”

So on December 27, I was standing behind a cash register refunding money for the Veg-O-Matics I’d sold the week before. “I’d like to get the money back for this thing,” the customer would say, handing me the orange and black box. They occasionally offered excuses such as “I already have one of these” or “I have no use for this piece of junk,” but what they wanted was cash. In almost every case the customer returning the Veg-O-Matic was not the person who’d bought it, so I didn’t consider the returns a criticism of my performance. I handed them the money and stuck the boxes and signed receipts under the register. At the end of the day, I toted the returned Veg-O-Matics to the storeroom and piled them up in the same space they’d occupied when they were new.

To compound this irony, the manager handed me a hammer at closing time on my first post-Christmas day as a cashier and sent me to the stockroom to smash the Veg-O-Matics the store had taken back. “Just bash those veggie things into little bits and put them back in the boxes,” he directed. “And while you’re at it, smash up these toys that didn’t get sold.” The manager didn’t explain why I needed to destroy so much perfectly good merchandise, and I didn’t ask. But I laid into my new task with gusto, obliterating hundreds of Veg-O-Matics along with Chatty Cathy dolls, Etch-A-Sketches, tin airliners, space guns, trains, battery-powered James Bond Aston Martin cars, Rock ’em Sock ’em Robots, Easy-Bake Ovens, electric football games, G.I. Joes, and the occasional Barbie doll, perfectly good toys that might have gone to poor children who’d suffered a sad Christmas. But it was exhilarating work — and strangely gratifying — an anti-capitalistic binge that assuaged the guilt I’d suffered from selling plastic crap to poor people.

But the days were long, and there was no time to hang out with my friends. When I got off work at 9 p.m., I was too worn out to go to parties or ride around with high school buds. I’d catch the bus back to Eastport and fall into bed. The following morning, I’d get up and do it again.

On my last day of work, a Friday, the manager shook my hand. “You’re a lifesaver,” he said, pumping my weary arm. “If you need a job next Christmas, just let me know.”

I smiled, gave him my college post office box number and asked him to send my check there rather than to my home address.

“You should get it before the 10th,” he said.

During the two-and-a-half weeks I’d toiled at Drug Fair, my parents hardly noticed my absence. I was a shadow who flitted in and out at odd hours. And I wanted it that way. I didn’t have to listen to them argue, which was their habitual method of communication during any holiday season when they were forced to remain in each other’s company for more than five continuous minutes. And if my parents didn’t realize the hours I was working, they’d have no idea how much money I was making. Had they an inkling of the cash I was likely to pocket, they would have given me that much less for tuition, room and board, and the endless hours I’d spent slaving at Drug Fair would have been for naught.

On the evening before my return to Elon, in honor of my having been invisible during the holiday season, my mother prepared lasagna, my favorite dish.

“You headed back tomorrow?” my father asked.

“First thing in the morning,” I answered, “I’m going to catch the bus.”

My mother looked puzzled. “It seems like you just got here,” she said.

“I’ve been working the whole time.”

“Good,” she said. “How much money did you make?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t gotten paid yet — and the wage at Drug Fair isn’t as much as it is at the Safeway. I’ll let you know when the check arrives.” I was lying, of course. I had no intention of telling anyone how much money I’d earned. It was nobody’s business but mine. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of eight books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards. This is an excerpt from his forthcoming book The Year We Danced: A Memoir.