HOMETOWN

Clear as Cursive

The handwriting on the scrawl

By Bill Fields

Hunting recently through a box of old stuff, most of which would have been thrown out long ago if I didn’t have a little pack rat in me, I found something I was glad hadn’t been tossed.

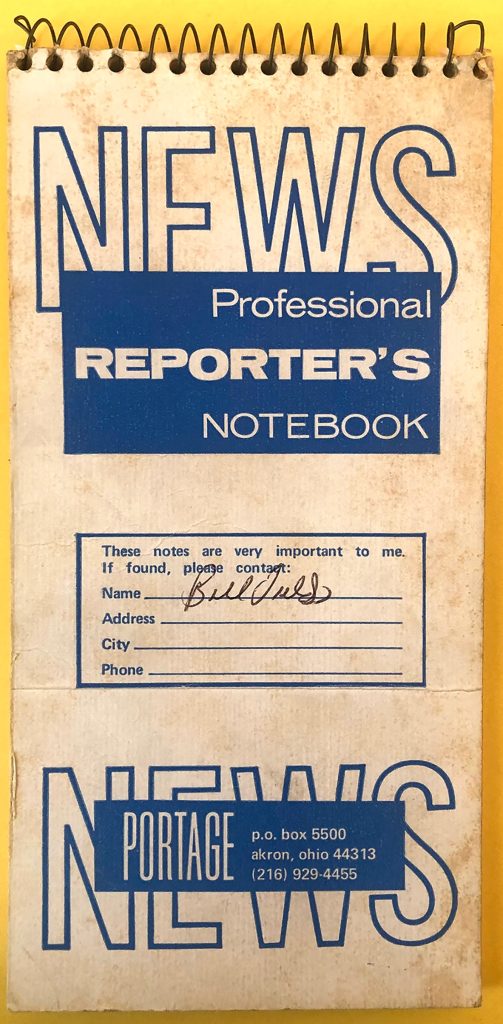

Over the years, I’ve filled many a reporter’s notebook. It’s a 4 x 8-inch lined pad with spiral rings at the top and cardboard covers, an essential tool for any journalist. Before the inconspicuously functional notebooks were widely available, while covering the turbulent civil rights movement in the American South for The New York Times in the 1950s and 1960s, Claude Sitton improvised them by cutting wider stenographer’s notebooks in half.

My discovery was of one of the first reporter’s notebooks I slipped into a back pocket, dating to 1979 when I was a student sportswriter for The Daily Tar Heel covering far less consequential events than Sitton — later the longtime editor of Raleigh’s News & Observer — was chronicling for the Times.

Beneath a creased and discolored front cover on its wide-ruled pages were my notes from assorted sporting events: North Carolina’s exhibition against the New York Yankees (green ink); a UNC-Duke baseball game (black ink); a spring football update from the Tar Heels’ second-year head football coach Dick Crum (blue ink).

“Going to keep it low and inside. Might even ask ’em to put the screen in front of the mound,” Carolina pitcher David Kirk told me the day before facing the two-time defending World Series champions. “If I get it up high, could be history. Chris Chambliss might hit one into Chase Cafeteria.”

“Sixth — P.J. Gay double off warning track.”

“OLB — Lawrence Taylor.”

Flipping through those old pages, I was pleasantly surprised that I could make out the vast majority of what I’d jotted down. Quotes from George Steinbrenner. “I’ve got professionals. Anybody who counts the Yankees out of the race because of spring is wrong.” Observations in the Yankees locker room before game time. “Pinella — cards, puffing cigarettes. Chambliss — 2 championship rings.” It wasn’t the neatest penmanship in the world, but it was readable.

I have notes from only a month ago that are harder to decipher.

That would no doubt be a disappointing admission for the person who taught me handwriting, Southern Pines third-grade teacher Peggy Blue, to hear. “Fine beginning in cursive writing,” Miss Blue noted on my report card in the fall of 1967. I earned straight As in “Writing” that year.

When it comes to notes taken on the job, there is a logical reason why I’ve become a sloppier notetaker. When I was in college, and for years afterward, tape recorders weren’t commonplace among journalists. Reporters took handwritten notes. In the case of a lengthy interview, if you weren’t on a tight deadline, you might type them up back in the office before writing a story. If you hadn’t written them so they were legible, you were out of luck.

Over the years, tiny digital recorders — and more recently, smartphones — have made it more convenient for journalists to record interviews. Convenient, verbatim audio leaves no doubt about what a subject said, but the technology has led to less thorough notetaking. Still, looking back on the period when I relied on pen and paper, I don’t recall being accused of misquoting anyone. Perhaps I inherited just enough of my mother’s steady, graceful penmanship, learned as a pupil of the Palmer Method in the 1930s, which endured into her 90s.

I can’t imagine not having learned how to write longhand, with joined letters. In this century, though, there has been a trend away from mandatory instruction in elementary school. I was stunned to find out that a young relative, who is now about the same age as I was when I wrote those notes in 1979, wasn’t taught cursive and only knew how to print block letters. About 15 years ago, many states removed longhand as a requirement. “The handwriting may be on the wall for cursive,” an ABC reporter quipped in the lede to a 2011 story about the trend.

Since then, however, education officials have realized that even in a predominantly digital age there is practical and cognitive value in knowing cursive writing. Many schools have reinstituted it as part of the third-grade curriculum. And someday, a budding reporter might even write down the profound thoughts of a coach, as I did with Dick Crum 46 years ago: “We want to play fundamentally sound football.”