Hometown

The Boys of Summer

In a league of their own

By Bill Fields

There aren’t too many highlights sprinkled in my sporting life. The enjoyment, perhaps by necessity, has come from playing not winning.

I’ve had a few moments when I flipped the script, most occurring in a small ballpark on Morganton Road in Southern Pines across from the National Guard Armory, where kids still play baseball today. Win or lose, though, on that compact field of dreams the crack of bat on ball and pop of ball in glove was a soundtrack of fun.

The site was home to the Southern Pines Little League field more than a half century ago when the Pirates, Cardinals, Dodgers and Braves duked it out on Monday and Friday evenings from spring into summer, games at 6:00 and 7:45. The lights really kicked in for the second match-up, especially early in the season, making it seem a bigger stage.

We were boys chewing Bazooka bubble gum, savoring the stirrup socks that made us look like major leaguers, hoping some pixie dust would fly out with each pat of the rosin bag, and quenching our thirst with some not-so-cool water from the dugout fountain.

Each season started the same way. There would be a trip to Tate’s Hardware on N.E. Broad Street to purchase a pair of rubber-cleated baseball shoes. We’d put on our flannel team uniforms and parade through downtown on a Saturday in May, then scatter to sell candy door-to-door to raise money for the Little League.

It was a long time before travel teams or meddlesome parents who want to make the games about them. Our moms and dads didn’t argue with umpires or second-guess coaches. They sat in the bleachers or in their cars beyond the field. They volunteered in the concession stand or as the public address announcer. They cut the grass and chalked the foul lines.

The outfield fence — 180 feet from home plate when I started Little League and lengthened to 200 feet before I was done — was covered with advertisements for local businesses not protective padding. I one-hopped a couple of hard hits off the metal barrier in left center but never hit a dinger in my three years with the Braves. I am a man without a home run or a hole-in-one but still hold out hope for the latter.

My most meaningful at-bat probably came in my first Little League season when I was 10, after moving up from the Minor League Tigers. We were playing the always formidable Pirates coached by Willis Calcutt. Their ace pitcher, a strapping boy who could have passed for a second-year Pony Leaguer, had a no-hitter going deep into the six-inning game. I somehow managed to make contact with one of his fastballs, hitting a blooper just over the second baseman into shallow right field.

I was better with glove than bat, a confident infielder who played second and a little shortstop before settling at third base when I wasn’t pitching. (I threw a knuckleball that, on my good outings, fluttered just enough to keep batters guessing.)

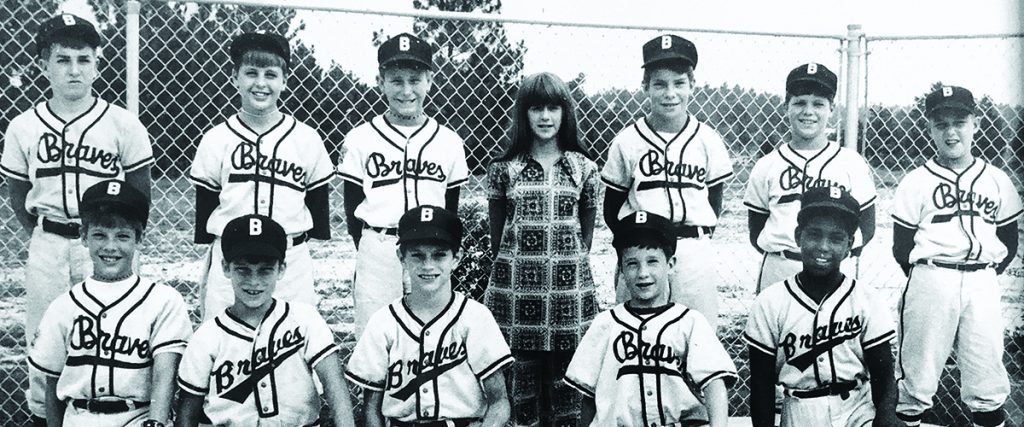

The Braves won the 1970 Southern Pines championship thanks to fellows who could really play like David Smith, Jay Samuels and Ian McPherson. (I’m far right, top row.) It didn’t hurt our chances that two of Coach John Williams’s sons, John Wiley and Mike, were part of the Braves. Coach was a de facto assistant to David Page and always willing to spend extra time working with us.

I made the All-Star team as a 12-year-old third baseman in 1971 when I had the privilege of playing for Jack Barron, whose many years of devoted community service in the Sandhills included being coach of the Dodgers for a long time. Mr. Barron did everything he could to prepare the All-Stars in our practices.

I’m not sure I knew there was a Warsaw, N.C., until we suited up in our blue and white Southern Pines uniforms and packed into a couple of station wagons for the two-hour drive east and our first game. But I’m certain I’d never seen a curveball on Morganton Road like the opposing pitcher threw that afternoon. I struck out in my one hapless at-bat, and my teammates didn’t fare much better. Our post-season didn’t last long.

But our disappointment, I recall, didn’t linger either. There was a stop for supper, at a restaurant that sold Andes Mints for two cents apiece at the cash register. We stocked up. Someone in the backseat figured out if a mint was released just so on top of the car, it would travel such that it would be sucked back into the wagon’s open rear window. The trick amused us for miles. If only we had solved the curve ball problem as proficiently. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.