HOME AWAY FROM HOME

Home Away From Home

The legend and allure of the Pine Crest

By Bill Case

It’s March 1961. You’re 45 and a lifelong resident of Erie, Pennsylvania, where you’re the respected managing editor of the local newspaper, the Erie Daily Times. You’ve worked at the paper for 20 years and been its editor for five. You have an excellent relationship with the paper’s owner. The job is yours as long as you want it. And you love it.

Your wife, Betty, comes from a prominent Erie family. Her father, Charles A. Dailey Sr., owned and operated Dailey’s Chevrolet from 1925 until his death in 1958, when Betty’s brother, Charles “Chuck” Dailey Jr., took over. The Dailey family has been among Erie’s foremost philanthropists. And your kids — Bobby, age 9, and Peter, age 5 — are happy in Erie.

Bob and Betty Barrett seemed the unlikeliest of couples to pull up stakes and seek a new life. While Bob was making a good living at the hometown paper, he wanted to own his own business. He discussed the possibility of partnering with Betty’s father in a second auto dealership in Erie, but that trial balloon blew away with Charles Sr.’s death. His passing did, however, result in a significant bequest to daughter Betty. With this nest egg and additional assistance from Betty’s mother, Elizabeth Dailey, the Barretts began looking for investment opportunities. But where?

“My dad had contracted pneumonia and worried he might not live long if he stayed where he was,” says Bobby Barrett, now 74. “He thought he stood a better chance of a long life if the family moved south. The Barretts and Daileys made regular golf trips to the Sandhills after my dad started playing in his mid-’30s. He fell in love with Pinehurst.”

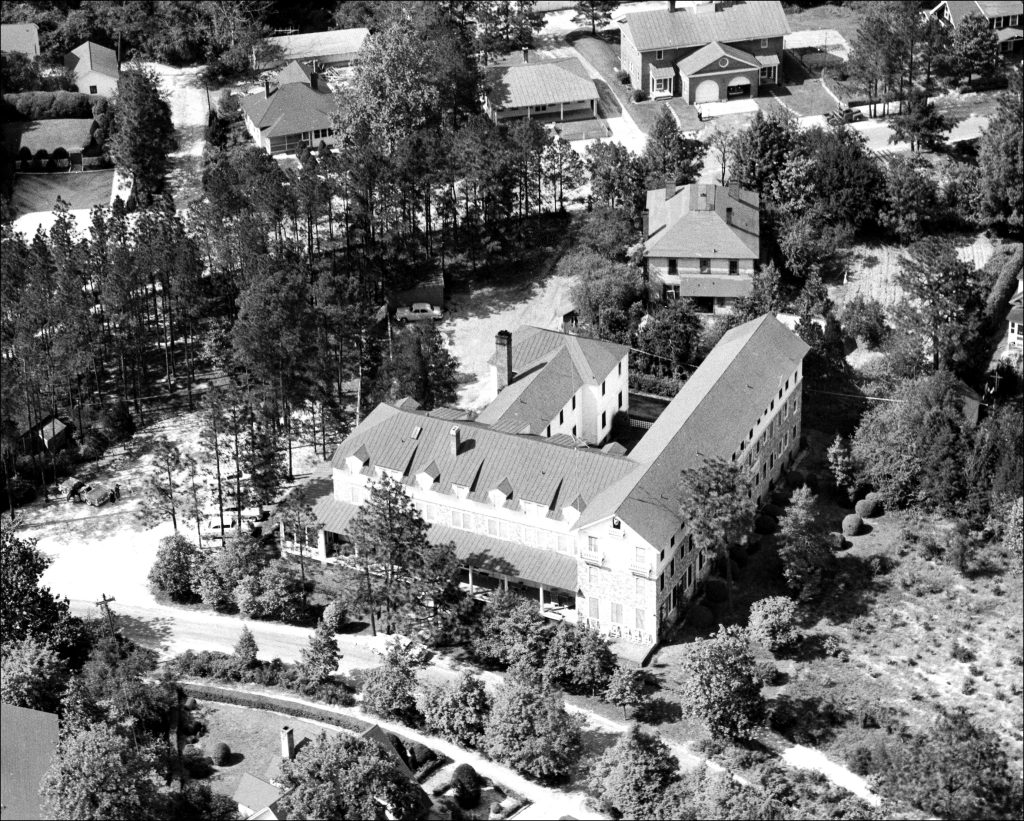

While walking down Dogwood Road during a March ’61 vacation, Bob happened to encounter Carl Moser, then owner of the Pine Crest, sweeping the inn’s front steps. The men struck up a conversation in which Moser indicated he would consider selling if the price was right. Bob and Betty began mulling over the idea of making an offer. While the Pine Crest was no luxury hotel, the Barretts knew that many golfers weren’t interested in cushy surroundings. The inn’s 44 modestly sized rooms provided a homey, affordable alternative to the upscale lodgings at the Carolina Hotel and Holly Inn. And it was a going concern. The Pine Crest boasted a solid base of recurring guests, migrating golfers who returned like swallows year after year. Some had been doing it for as long as the inn had been in existence, 48 years.

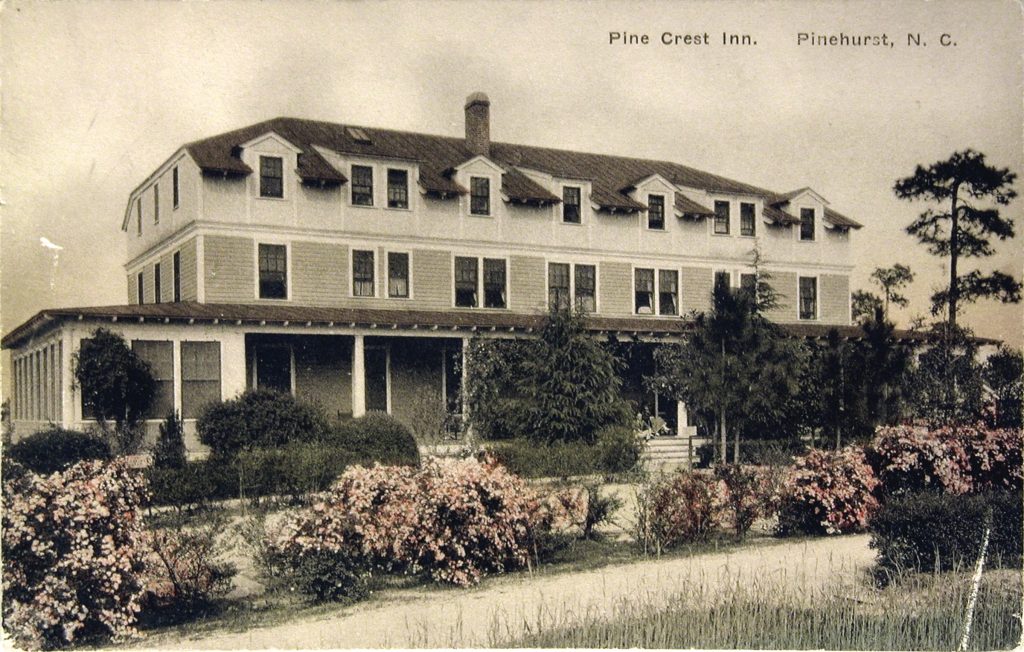

Built in 1913, the hotel was the creation of enterprising innkeeper Emma Bliss. A New Hampshire native, Bliss had spent the previous nine years (1903 to 1912 ) managing The Lexington Hotel — where The Manor is today — which primarily served as a boarding house for resort employees. Leonard Tufts, who controlled most business activity in Pinehurst, hired Bliss after being impressed with her surehanded management of a Bethlehem, New Hampshire, inn.

Bliss shuttled back and forth with the seasons between managing The Lexington and her inn in Bethlehem. Possessing an entrepreneurial spirit of her own, she aspired to own a hotel herself, not just manage one. In January 1913, Tufts sold Bliss property on Dogwood Road, adjacent to the Lexington. By year end, she had erected and opened the Pine Crest Inn.

The Pinehurst Outlook hailed the inn’s arrival as a “delightful addition to the list of hotels; its comfort is suggested by the charm of its exterior . . . Modern in every particular, it provides several suites with private bath; radiant with fresh air; sunshine, good cheer, and ‘hominess’.”

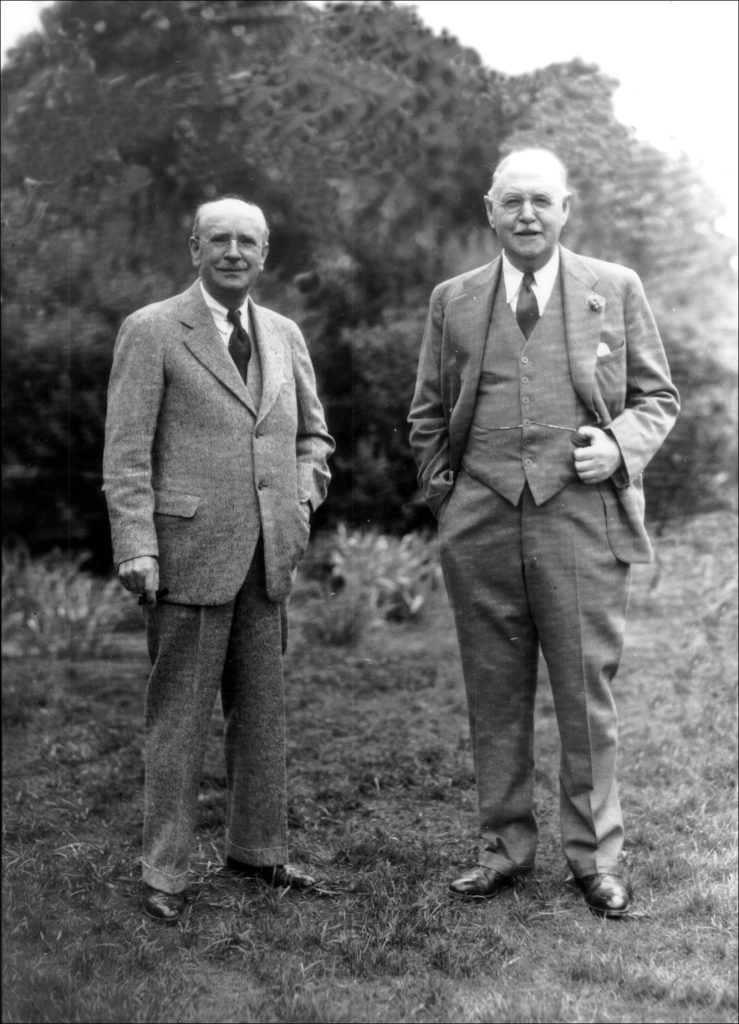

Bliss operated the Pine Crest for seven years before selling it in April 1920 to Donald Ross and his fellow Scot expatriate W. James MacNab for $52,500. Ross, Pinehurst’s patron saint, was hitting his stride in the golf course architecture business and supplied the money for the purchase. MacNab managed the inn.

Instead of simply returning to run The Lexington, Bliss bought that property and tore down the old hotel. In its footprint, she erected a new lodging house — The Manor, a far more upscale house than its predecessor. Neither Tufts nor Ross seemed to begrudge Emma’s maneuvering, and Bliss owned and operated The Manor until her death in 1936.

To keep pace, Ross financed several improvements at the Pine Crest. He summarized them in correspondence with a prospective buyer in 1939: “Ever since I purchased the property, I have put back every cent earned and also some additional cash in the furnishing and maintenance of it. . . . Among the improvements I made are a telephone in every room and a Grinnell fireproofing system.” Ross dropped an additional $35,000 adding the inn’s east wing.

The Ross era at the inn began winding down after MacNab died in 1942. Aging himself, Ross chose to sell the inn in 1944 to the Arthur L. Roberts Hotel Company for $65,000. The company operated hotels in Florida, Minnesota and Indiana. The company’s founder, Arthur L. Roberts, arranged for title to the Pine Crest’s property to be placed in his individual name.

In September 1950, Carl Moser came to Pinehurst to manage the Pine Crest. Moser had extensive experience in hotel management and customer service. In 1941, the native New Yorker managed the Officers Club at Fort Bragg while serving in the Army Reserve. He had subsequent stints managing hotels in Greensboro (the Sedgefield Inn), Charlotte (Selwyn Hotel) and Stamford, Connecticut.

Along with his wife, Jean, the Mosers chose to live in the Pine Crest, occupying rooms 6, 8 and 10 on the first floor. Daughter Carlean joined her parents in these cozy quarters following her birth in May 1953. Arthur L. Roberts passed away in October 1952, and the trustees of his eponymously named company began liquidating its portfolio of hotels. In June 1953, Carl and Jean Moser entered into a land contract with Roberts Hotels to buy the Pine Crest Inn for $65,000 — $12,000 down and the balance paid over time.

By virtue of the deed records, Roberts’ heirs thought they owned the property, not the company. If they were right, neither Roberts Hotels nor the Mosers had any cognizable interest in the property. To resolve the issue, litigation was instituted in Moore County in September 1953. After hearing evidence, a local jury determined that (1) Roberts was acting in his capacity “as president and agent” of Roberts Hotel in effecting the 1944 purchase from Ross and MacNab; (2) it was Roberts Hotels, not Arthur Roberts individually, that paid the $65,000 purchase price; and (3) Roberts Hotels was not “under any duty to provide for the said Arthur L. Roberts in purchasing said property.”

Roberts Hotels was declared the inn’s rightful owner. Carl and Jean Moser breathed a sigh of relief; they had been dealing with the right party after all. And if in the future they wanted to sell the inn, they could do so.

Eight years later, the Mosers were ready to entertain offers, but according to daughter Carlean, her parents did not initially consider the Barretts serious prospects. After the sidewalk chat between Bob and Carl, there was no immediate follow-up. Not long afterward, however, representatives of the Barretts — probably Betty and her brother Chuck, who had experience in evaluating businesses — came to inspect the premises. Negotiations heated up, and in May 1961, the Barretts agreed to buy the Pine Crest for $125,000.

Since the Dailey side of the family was providing the capital, it was determined Betty would hold title to the property.

Unlike Carl and Jean, the Barretts chose not to reside in the Pine Crest. They bought Chatham Cottage (now Barrett Cottage) across Dogwood Road and made it the family’s home. Over the summer, Bob moved his wife and children to Pinehurst, took a crash course in hotel management, and announced a fall reopening date of October 12, 1961.

Eight-year-old Carlean Moser was heartsick to be departing the inn. “My dad broached the subject by asking whether I thought it would be fun for us to live in our own house,” recalls Moser, now 74 and living in Washington, Georgia. “I said it wouldn’t be fun if it meant I had to make my own bed or couldn’t order off a menu like I could always do at the inn.”

To Carlean the Pine Crest’s employees were like family. Some doubled as playmates. Carl Jackson, the inn’s head chef since the Donald Ross days, was a special favorite. The burly African American would spot Carlean entering the kitchen and commence beating the pots and pans hanging over the counter. The cacophonous clanging delighted the little girl. “I nicknamed Carl “Boom-Boom,” says Moser. “He was kind and fun.”

She played with guests too. At age 6, she sat on the lap of 19-year-old lodger Jack Nicklaus, in town for the 1959 North and South Amateur (which he won). ”We sat in the lobby watching the Mickey Mouse Club on television, and I wore my mouse ears,” says Moser. “Jack was very shy then. As long as I was on his lap, no one was going to bother him.” (Nicklaus bunked in room 205 in ’59; 26 years later, son Jack Jr. also roomed in 205 while winning his own North and South title).

The inevitable pitfalls of Barrett’s unlikely career switch presented the sort of scenario reminiscent of the 1980s comedy Newhart, the long-running television show about a New York City-based author of travel books, played by Bob Newhart, who abandons his former life to operate a 200 year-old Vermont inn.

In contrast to Newhart’s neighbors — Larry, Darryl and his other brother Darryl — a coterie of dedicated employees kept Barrett on track. Foremost was Jackson, who proved to be the ultimate lifer, remaining the inn’s chef until 1997, a full 61 years of employment. Starting in 1936 as “the pot washer” in the kitchen, Jackson began preparing meals about five years later.

“I started cooking under a German lady, “he told a Pilot interviewer in 1986. “She became ill and left it in my hands.” Jackson mastered a variety of Southern-style recipes. His pièce de résistance was “Chef Jackson’s Famous Pork Chop,” 22 ounces of meat “so tender you can cut through it with a fork,” effused writer John March in his 100th anniversary piece “Legends of the Pine Crest.” The famous dish is still on the menu.

Barrett insisted the kitchen serve the best cuts of prime meat. Specially ordered steaks came from Gertman’s in Boston. Freshly squeezed orange juice graced breakfast tables. Assisting Jackson in the kitchen was his apprentice and nephew, Peter Jackson. Peter had been employed at the inn for three years when the Barretts arrived and worked in tandem with his uncle for nearly 40 years. Carl Jackson’s cousins Elizabeth “Tiz” Russell and Josephine “Peanut” Russell Swinnie were sisters and permanent fixtures on the housekeeping staff. Tiz also babysat for youngsters Bobby and Peter.

Then there was Peggy Thompson, who supervised the dining room for decades, charming the guests and making a point to know them on a first-name basis. She recruited Marie Hartsell, who labored at the inn for 33 years, first on the wait staff, then as kitchen supervisor. Though Hartsell did not fancy herself a cook, she assisted in the kitchen baking pies. Her tasty banana cream became a Payne Stewart favorite.

And Betty Barrett was a worker bee too. She assumed the duties of an assistant manager, working behind the counter, preparing menus and ordering supplies. Even Betty’s mother, Mrs. Dailey, a frequent presence in Pinehurst, pitched in, assisting with the inn’s bookkeeping.

Though it took time for Bob Barrett to find his innkeeping sea legs, his personality proved perfectly suited for his position. A natural schmoozer, Barrett easily befriended guests. A major factor was his resourcefulness in arranging golf itineraries, an aspect of the job he enjoyed. During the ’60s, independent hotels like the Pine Crest had little difficulty getting starting times at the Pinehurst resort, Mid Pines and Pine Needles — a lifeblood for the inn.

Barrett also expanded the Pine Crest’s footprint. When the old telephone exchange building next to the inn was offered for sale, he outbid The Manor to get it. The revamped “Telephone Cottage” would become a favorite lodging choice for pros like Roger Maltbie and Ben Crenshaw.

Things ran relatively smoothly for the Barretts throughout the 1960s, but that changed when the Tufts family sold Pinehurst in 1970 to Malcolm McLean. His Diamondhead Corporation promptly converted vast wooded acreage into housing subdivisions, tacking on Pinehurst Country Club memberships to lot purchases. With the ranks of new club members swelling, securing tee times by the independent hotels became a nightmare. Under the new regime, outside starting times could, at best, only be reserved three days in advance.

Barrett did find a lifeline at the resort who assisted him in coping with the new order. Young Drew Gross, the first assistant to the resort’s director of golf, greased the skids for Barrett, keeping him abreast of last-minute openings on the resort’s tee sheet. The two men formed a bond that would have lasting impact.

Despite Gross’ assistance, the early 1970s were a bleak time for the Barretts. Bobby recalls his dad becoming so frustrated with the starting time debacle he considered suing Diamondhead for ruining his business. Instead, Bob and Betty decided to get out altogether. In 1974, they sold the Pine Crest to Richmond businessman Nat Armistead. The Barretts agreed to take periodic payments from the buyer and to continue managing the inn for an interim period.

The Barretts were in the midst of planning their future when tragedy struck in 1975. Betty Barrett, just 53, died suddenly at home. The family was devastated. To make matters worse, Armistead defaulted and Barrett (now in joint ownership of the inn with sons Bobby and Peter) remained saddled with a teetering business.

Barrett rededicated himself to improving the Pine Crest’s facilities. He installed air conditioning in 1977, allowing the inn to stay open during the summer. He reduced the number of rooms in the hotel to 35, increasing the size of several, and added rooms by moving out of Barrett Cottage and converting it into an eight-room headquarters for larger golf groups. When Diamondhead exited the scene, obtaining tee times at the resort eased up and new courses, like the Carolina Golf Club and The Pit, were open for play.

A 1978 change in state liquor law provided a major boost to the Pine Crest’s bottom line. North Carolina had historically been a “brown bag” state; customers brought their own booze to restaurants, and the bartender would mix their drinks. But with passage of the new law, inns and hotels could sell liquor themselves. Originally situated in the Crystal Room at the western end of the inn, the bar was ultimately moved to its current location, just off the lobby. Bill Jones, the flamboyant personality who tended the bar, began attracting regulars to the watering hole known as “Mr. B.’s.”

While Jones’ long blond hair gave him the outward appearance of a California surfer dude, he was actually a high-voltage comedian, flashing his rapid-fire albeit caustic humor. John Marsh wrote that Jones’ “rapier-like wit reminded many of comedian Don Rickles, and it was generally conceded that you weren’t really accepted within the Pinehurst community until you had been insulted by Bill Jones.”

Adding to the atmosphere at Mr. B’s were regular appearances of renowned golf writers Bob Drum, Dick Taylor and Charles Price, all bon vivants. They formed the bar’s notorious “Press Row.” A Pittsburgh Press alum, Drum was Arnold Palmer’s muse and later a feature presence on CBS golf telecasts. Taylor was the longtime editor in chief of Golf World, and Price was the author of several noteworthy books (A Golf Story: Bobby Jones, Augusta National, and the Masters Tournament and Golfer at Large), and at one time or another wrote for every golf publication worth the ink. Bob Barrett often permitted these luminaries, as well as other notable golf figures, to imbibe on the house, or at least at a steep discount. And they made the most of it.

Just about everyone in Drum’s family worked at the Pine Crest in some capacity. Son Kevin served as busboy or, as he puts it, “the relish tray girl.” Bob Drum himself served as a celebrity bartender from time to time, standing in for Jones. On one such occasion, a customer ordered a “George Dickel.” Drum, a man of substantial girth, broke a sweat rummaging through the bar in feverish efforts to locate the whiskey. Once he was ready to pour, the guest said, “Oh, and mix Coke with it.” The thought of despoiling fine Tennessee whiskey so offended Drum he suggested the man take his business elsewhere.

Barrett considered his generosity toward Press Row money well spent. He’d been in the newspaper trade himself, and the writers did provide the Pine Crest some favorable publicity. Mr. B.’s soon began appearing near the top of ubiquitous listings for “the best 19th holes in golf.”

Jones fit right in, moonlighting a golf column for The Pilot. Despite his bluster, he was a revered part of the scene, and it was a shock when Jones passed away in 1995 at age 40.

Bobby Barrett’s wife, Andy Hofmann, who has worked in reservations for 45 years, got teary-eyed recalling Jones’ passing. “Bill said he wasn’t feeling well at work on November 13th,” she says, “went home, and by the 15th he was in the hospital. He died December 5th.”

Jones’ successor behind the bar, Carl Wood (now the owner of Neville’s in Southern Pines), was at first unaware of the local luminary discount. He recalls two-time U.S. Amateur champion Harvie Ward sitting down at the bar with a friend and ordering a Bombay. “That will be $6, sir,” said Wood. A clearly mystified Harvie turned to his companion and observed, “I think he’s serious!”

The return of PGA Tour events to Pinehurst, beginning in 1973, brought increasing numbers of golf greats into the village. Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Payne Stewart, Bill Rogers, Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite are just a few of the champions who stayed, ate or drank at the Pine Crest. And their appearances led to memorable anecdotes.

Barrett made friends with the great, the not-so-great and the run-of-the-mill alike. Probably his best buddy in PGA circles was Pinehurst pro Lionel Callaway. Whenever there was a March snowstorm, Bob would call on Lionel to give golf lessons in the lobby, a tradition begun by Donald Ross, who likewise provided instructional tips to snowbound guests when he owned the inn.

Callaway’s greatest contribution to the Pine Crest is the celebrated chipping board. No golfer’s Pinehurst pilgrimage is complete without trying to knock a ball into the hole in the wooden board covering the old fireplace. Ben Crenshaw has the record for consecutive chips holed — 28. Not everyone is as accurate. The fireplace mantel has more dents than a car in a demolition derby. The glass protecting the painting of Donald Ross above the fireplace was smashed so often, it was ultimately bulletproofed.

Both of Barrett’s sons became skilled golfers. Bobby Barrett made the final field of the 1969 U.S. Amateur, competed at medal play that year at Oakmont Country Club, America’s most demanding championship test. Not to be outdone by his elder sibling, Peter Barrett would subsequently make a strong run at winning the Carolinas Open. He did win the 1974 Pinehurst Country Club championship, his 283 total edging Pinehurst mogul-to-be Marty McKenzie by one shot.

Both boys were advancing in their professional lives as well, though on different tracks. Bobby obtained professional degrees at Duke and UNC. He became a CPA catering to individuals and small businesses (including the Pine Crest). His office is located on Community Road just behind the inn. Bobby also obtained a law license but never practiced. “I never lost a case,” he deadpans.

Groomed by Bob to one day succeed him as the inn’s general manager, Peter attended hotel management school. Given his own golf chops, he related well to the younger pros, like Payne Stewart, who became a friend. It was he who created a slogan touting the inn’s no frills persona: “A third-rate hotel for first rate people.” It supplemented the inn’s other tagline, employed since the Emma Bliss era: “An Inn Like a Home!” The youngest Barrett also sold real estate.

In the course of Bob Barrett’s first 37 years of the inn’s ownership, a slew of PGA Tour events were contested at Pinehurst, but no professional major championships. So it was a thrill for the 84-year-old when the USGA brought the 1999 U.S. Open to Pinehurst. And not surprisingly, both the Pine Crest and a longtime employee became involved in the lore surrounding Payne Stewart’s epic victory. Payne ate dinner at the Pine Crest after an early round of the championship and affixed a hyper-enlarged signature on the wall of the ground floor men’s room. The passage of time has rendered the script undecipherable, but his outsized signature is replicated in the lobby.

Margaret Swindell, a mainstay behind the desk for decades (you’re a newbie until you’ve been employed at the Pine Crest for at least a decade), had a memorable encounter with Stewart prior to his final round. Swindell was working at her then-primary job with Pinehurst Country Club at the Learning Center when Payne approached her counter and requested a pair of scissors. He did not like the feel of his rain jacket and wanted the sleeves trimmed away.

Swindell and a co-worker held the jacket taut while Stewart snipped. She placed the detached sleeves in a drawer, thinking nothing more about the remnants until Stewart won the championship, and a ruckus was made afterward concerning his sleeveless rain jacket. Today, the sleeves and scissors are displayed at the World Golf Hall of Fame in an exhibit titled “Style and Substance: The Life and Legacy of Payne Stewart.”

Bob Barrett’s hope that moving South would lead to a long life came to pass. He died at age 89, two months after the 2005 U.S. Open at Pinehurst. John Dempsey, the longtime president of Sandhills Community College, gave the eulogy.

“Bob lit up every room he ever entered,” said Dempsey. “He was truly the community’s innkeeper.” Dempsey, who first met Barrett while guesting at the Pine Crest many decades ago, credits Bob for persuading him to apply for the position of SCC’s president, a job he would hold for 34 years.

Though already performing the bulk of managerial duties, Peter Barrett formally became the Pine Crest’s general manager following his father’s death. But additional leadership was required, and it came from Bob’s old friend.

Drew Gross was hired in 2011 as the Pine Crest’s resident manager. Gross had been involved in a diverse array of activities since his Diamondhead days: caddying on tour, event planning, cultivating relationships with airlines for National Car Rental, and operating a company that provided retired baseball players moneymaking opportunities. It was Gross who arranged for retired greats like Sparky Lyle, Lew Burdette, Tommy Davis and Warren Spahn to bivouac at the Pine Crest during the old ballplayers’ 1992 Pinehurst golf get-together.

Recognizing the inn’s history constitutes a major part of its appeal, Gross organized a gala centennial celebration of its founding on Nov. 1, 2013. Bagpipers played, dignitaries spoke, Hoagy Carmichael’s son, Randy, performed “Stardust,” and a bronze bust of Donald Ross was unveiled.

Free drinks at Mr. B’s are a thing of the past. Head bartender Annie Ulrich makes sure of that. The Long Island native came to the Pine Crest as a fill-in barkeep during the 2014 Open. Ulrich, whose husband, Gus, is a two-time North Carolina Open champion, loves her job. “Making one person happy is great,” she says. “But at any one time, I can make 20 people happy.” The narrow passage between the piano and the bar is now called “Annie Avenue.” Even as Mr. B’s flourishes, courses like Pine Needles, Mid Pines, Southern Pines, Talamore, Mid South, Tobacco Road, etc., continue to work with the inn booking tee times.

It is true that the Pine Crest celebrates its history — the three barstools at Mr. B’s bearing brass plaques dedicated to the long departed trio of Drum, Price and Taylor; the two Donald Ross sculptures and the painting of Ross over the fireplace; the many images of long-gone golf heroes; and the tiny monument to the succession of orange cats, Marmalade or Marmaduke depending on the feline’s gender, that patrolled the porch — but this is no museum. Stop by on a weekend night when music is playing, folks are dancing and guests are chipping, all in the snug, yet somehow uncrowded, lobby. It’s vibrant, intimate and fun.

There’s no place quite like it.