DEEP BACKGROUND

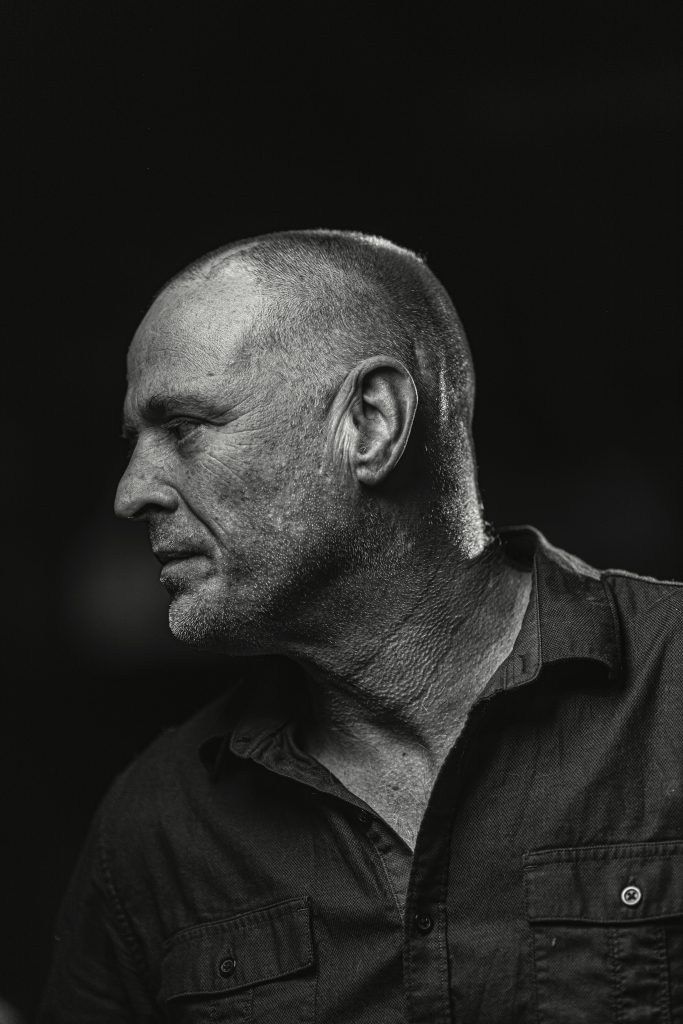

Deep Background

Battling the clock for art

By Jim Moriarty

Photographs by Tim Sayer

“I’m officially bionic,” says Derek Hastings. “I have to charge myself once a week.”

In early August Hastings underwent deep brain stimulation (DBS) implantation at Duke Raleigh Hospital. The surgery required placing two electrodes in his brain, attached to wires that run under the skin to a battery roughly the size of a Zippo lighter installed subcutaneously on his chest not far from his heart.

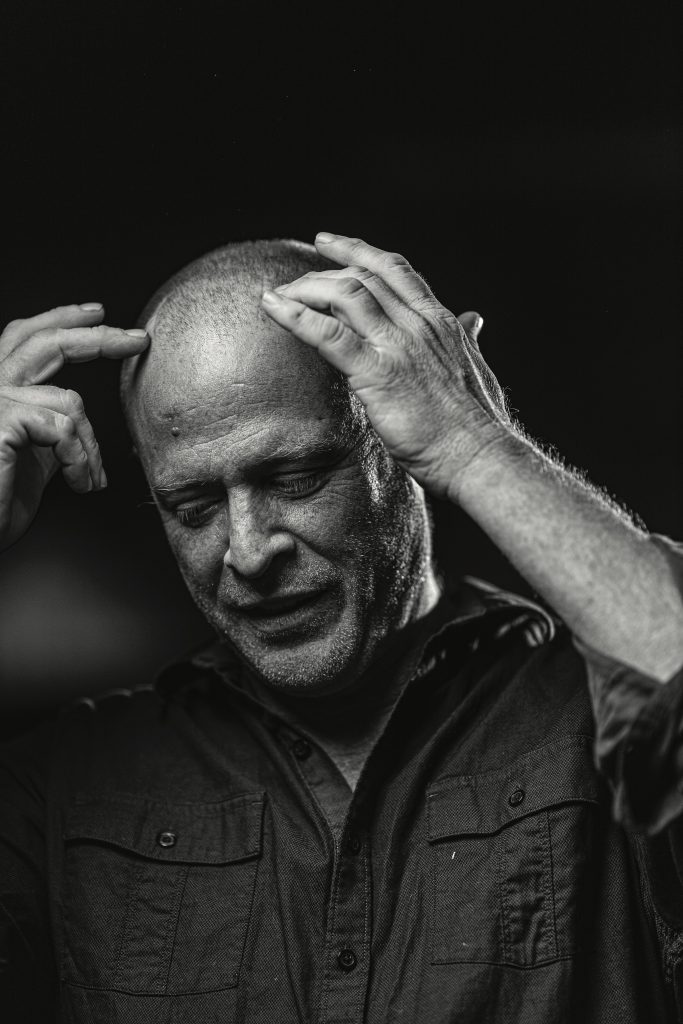

Hastings has Parkinson’s disease, and the surgery is designed, in combination with medication, to minimize his uncontrollable movements (dyskinesia) and tremors.

Halfway through the operation his neurosurgeon brought him out of anesthesia to test whether or not the electrodes were in the right spot. They asked Hastings to extend his arm. His hand shook violently. The surgeon turned on the device and instantly his hand stopped moving. It was like going from Class V rapids to a tidal pool. Pleased with the results, they put him back under and finished the procedure.

Was he nervous before the surgery? Damn right. Who wants someone tap dancing through their skull? But deep brain stimulation was, perhaps, the only way Hastings, at 54, was going to be able to recapture a modicum of what passes for normalcy in a life that was decidedly not normal.

For the last decade and more, you could find Hastings and, as Elliott Gould says in Ocean’s Eleven, “a crew as nuts as you,” pulling all-nighters in a string of warehouses in Southern Pines creating backdrops for The NFL Today show on CBS. With apologies to The Jetsons, covering live sporting events requires something akin to a steamer trunk full of Spacely sprockets and Cogswell cogs. If football is the ultimate team sport, televising it is the ultimate team undertaking. There are directors and audio engineers and replay operators and graphics coordinators and researchers and electrical engineers and camera operators and talking heads and on and on and on.

What Hastings, who’s had a hand in winning three Emmys (two at ABC, one at HBO), and his volunteer crew did was manufacture “feel.” The gritty artwork of their backgrounds gave the pre-game interviews a unifying and distinguishable look achieved because it was done by hand and not by computer. “It was like the glue sprinkled through the show, an aesthetic thread that would kind of tie it together,” says Hastings. “Subconsciously for most people.” It was also more expensive than a graphics app and, in a time when network TV doesn’t reign as supreme as it once did, something of a luxury.

Though “luxury” is hardly the word for the work. The deadline for the finished product was 10 a.m. on Saturday morning. Once Hastings got the subject matter and bullet points from New York, usually on a Wednesday, implementation was up to him. He had a three-day turnaround, soup to nuts. The core group of Moore County helpers included Patrick Phillips, his wife, Jen, Matt Greiner and Karen Snyder. They worked construction, painted sets and backdrops, built a dolly system with — if you can believe it — roller blade wheels, made sunrise runs to Bojangles, helped with bookkeeping, picked up overnighted packages of photos, and pretty much did everything and anything to help a friend out.

“I figured I could come in and help Derek with whatever he might not be able to do physically,” says Patrick Phillips. “If I saw that his alarm was going off for medications, I’d let him know. If he was starting to feel uncomfortable, or get bad, I’d try to make sure he’d eaten. Anything he needed, really. My mentality was, I wanted to give him more longevity.”

Hastings grew up in Miami, the son of two artists who, though divorced, both ended up living in Pinehurst. His father, Lynn Courtlandt Hastings, who passed away in the fall of 2014, was an interior designer, but his printworks are in the collections of both the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. His mother, Sandra, who also suffers from Parkinson’s, has won prizes for her ceramics in Arts Council of Moore County competitions at the Campbell House. “I really didn’t have a shot at doing a 9-to-5 banker’s job,” says Hastings.

In something of a misdirection, Hastings went north from south Florida to attend college at Michigan State University, where his major was a smorgasbord of theater, communications, English, film studies and art history. “Which meant unemployment,” he says. While he was at MSU, however, he latched onto half a dozen jobs with ABC as a runner for college football games. Post graduation, he did a stint as a lobbyist’s aide, then moved to L.A. to be an actor.

“I lived in a closet above Arnold Schwarzenegger’s restaurant,” he says, but quickly wound up back in Michigan, out of work and sleeping on a friend’s couch. He reached out to ABC and began going anywhere and everywhere they needed someone. Horse races in Kentucky. Time trials in Indianapolis. The odometer on his leased Mustang recorded miles from Maine to Miami.

“I found out that they had one position in New York that they hired every year from the pool of runners. At the time ABC sports was the global sports leader. They were everywhere. I’m like, I’m going to get that spot,” says Hastings. He did.

Bob Toms, an ABC exec, recognized Hastings’ artistic skills and took him under his wing. Hastings quickly achieved launch velocity. He got his first associate producer contract at 27, bumped up to producer in 1999 when he was honored for design and art direction for the opening graphics of the “Showdown at Sherwood” with David Duval and Tiger Woods, followed by more accolades for work on Super Bowl XXXIV between the St. Louis Rams and Tennessee Titans in 2000. Hastings left ABC to work for Tupelo Honey Productions until the 9/11 terrorist attacks brought its business to a sudden halt, launching him into the freelance world.

Six years later Hastings won another Emmy as a field producer for HBO Sports’ 24/7 Mayweather/De La Hoya. “I spent six weeks in Puerto Rico with Oscar, planning the days, what we were going to shoot,” says Hastings. “That was kind of the pinnacle of me doing that stuff.”

Though Hastings didn’t receive formal credit on ESPN’s award-winning 30 for 30 series production Run Ricky Run, he was instrumental in getting it made. The show’s writer and director, Sean Pamphilon, spent six years shooting the documentary on Miami Dolphins running back Ricky Williams. Pamphilon and Hastings are something of kindred spirits. “It was like we were rainbow fish who saw each other in this sea of sameness,” says Pamphilon. “He helped me do the sizzle reel for Run Ricky Run. We were both broke. We edited it in a trailer park near Santa Cruz, California. It was like The Odd Couple.”

They put together 20 minutes that was so compelling ESPN was hooked before it finished. Run Ricky Run remains the only one of the series shot in cinema verité. “I don’t get that deal if it’s not for Derek,” says Pamphilon.

After Lynn Hastings moved to Pinehurst from Miami in 1990, Derek was a regular visitor. He met and married Rachael Wirtz, who worked for his father. Now divorced, the couple have two daughters, Reade and Elizabeth. It was his daughters who took Hastings off the road in 2011.

“I told myself I wasn’t going to miss another Christmas with my kids,” says Hastings. “I bought this beat-up car and drove all the way back from California. Ended up living in Anthony Parks’ pool house for about nine months.”

There remained the minor hurdle of making a living in a small Southern town when your day job involved working on location with NFL athletes and franchises in 32 cities across the country. Like the players themselves, Hastings got there via the draft.

“We did stuff for NFL Network that kind of got my friend at CBS interested,” says Hastings. The friend at CBS is Drew Kaliski, who was named the producer of The NFL Today (among many other credits) in 2013. “We did all these backgrounds for the NFL Combine. We called it ‘First Draft.’ It was a series of short features on the top 50 players. We’d create these sets, and the players would come up, and I would direct them.” Kaliski thought Hastings could bring a similar feel to their Sunday show interviews.

Hastings’ link at the NFL Network, where he contributed freelance jobs from 2013-20, was Brian Lockhart, another one-time up–and–comer at ABC, who today is ESPN’s senior vice-president in charge of all original content. “My first time getting a chance to work with Derek was around 1997-98,” Lockhart says. “I would see the things he was doing, and I would be like, how does that guy do that? I remember being on his heels, trying to soak up all the knowledge he had. Derek was the first person in this business who said to me, ‘Man, you could be really good at this. Trust your instincts.’ He was so generous with his feedback and his encouragement. He was an inspiration then and remains an inspiration to this day.”

The first “studio” Hastings cobbled together in Southern Pines was an open space in a storage building. He worked by the headlights of his car. “I had to call AAA like three or four weeks in a row when my car battery died at 3:30 in the morning. Sometimes friends would come by and give me a jump,” says Hastings. “I think we did six or seven weeks in there.”

In the early going Hastings and members of the merry band built the backgrounds, broke them down, drove to the relevant city and put them back together again. Then, one week in season two, it snowed in Green Bay and a flight got canceled.

“I told my boss I thought I could get some camera gear quickly,” says Hastings, who now uses a broadcast-quality Canon C-300 and multiple lenses rented from a place in Cincinnati. “We built a couple of sets on the fly, shot them and got it up to New York, and they loved it.” No more trips to Green Bay, or anyplace else.

While the backgrounds were becoming more complex and the warehouse space more expansive, Hastings’ health was deteriorating. The tremors began nine years ago, and it was five years before his Parkinson’s was diagnosed. If not for the help of his crew, the work of the last few seasons would have been impossible. At the conclusion of last year’s Super Bowl, they shared a Champagne toast.

“This year felt a little different,” says Hastings. “It felt like closing time. We could just kind of see the writing on the wall.” CBS, recently acquired by Paramount Skydance, didn’t renew Hastings’ contract for a 12th season.

His mother’s Parkinson’s has descended into dementia, and Hastings is looking for a care facility for her near where he now lives in Wake Forest. In the meantime, he shuttles to and from Southern Pines to see her and his cohorts.

His brain surgery has no positive effect on the progression of his disease. It’s a quality-of-life issue and a lifeline, he hopes, tethered to the business he’s spent 26 years doing. He’s had the Super Bowl trophy in his hands at least 15 times. He’s had the run of the NFL Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, after dark. He brought his disc golf movie, Chains — along with some of the best disc golf players on the planet — to the Sunrise Theater. He was on the goal line at the Super Bowl in 2010, eye to eye with Anthony Hargrove, the subject of the NFL Network piece “Sinner to Saint” that he helped produce, as the defensive end celebrated. “I have so many things to be grateful for. This business has been amazing,” he says.

Field producing was always Hastings’ wheelhouse. “My kids are grown now. I can travel again,” he says. Deep brain stimulation, he hopes, was the boarding pass. The great unknowable is whether his professional connections and resume will be enough to overcome the stark reality of his Parkinson’s.

“I don’t know what’s next. I really don’t,” says Hastings.

“Myself and Derek, you can never count us out,” says Pamphilon. “I hope the surgery gives him the dexterity and the comfort that he needs to be able to do his job at the highest level, not just because of his capacity to earn but because it feeds your soul. When you have the ability to do something you know no one else can do, that will keep you going. That will bring the sun up for you.”