Arnold Palmer’s sentimental journey

By Bill Case

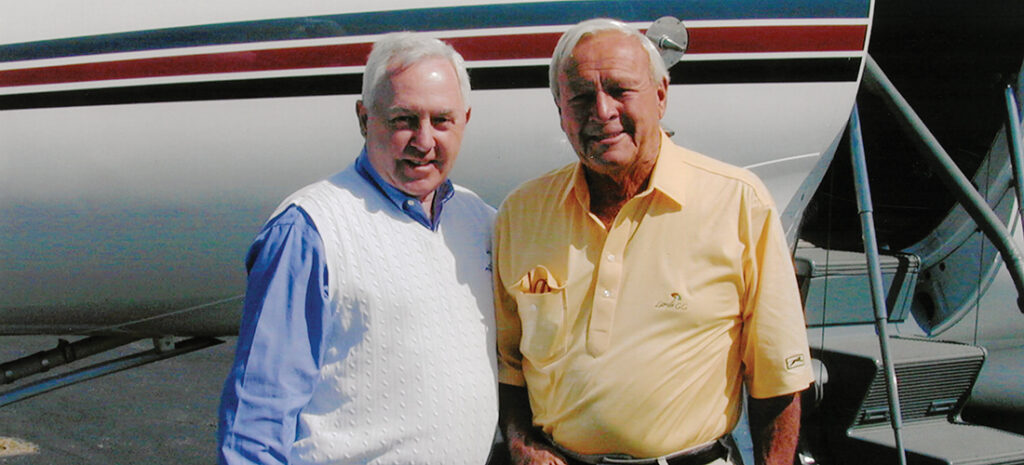

Feature Image: Stephen Boyd with the King (Photograph courtesy of Stephen Boyd)

There is no denying he was a magnificent player. Arnold Palmer’s glistening record of 62 PGA tour victories, including seven major championship titles, unquestionably ranks him in the highest echelon of golf’s greats. But it would be a stretch to place him at the top of that elite list. Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, Ben Hogan and Sam Snead all outperformed Palmer in terms of winning tournaments. And though there was a period when the Latrobe, Pennsylvania, native was the game’s best player, his dominance was relatively short-lived. Arnold won all seven of his major championships from 1958 to 1964.

But even if he was not the greatest golfer of all time, Palmer achieved unique success in the sport in other ways. From his emergence as a superstar in 1958 until his death in 2016, he reigned as the most beloved figure in the game; a man whose endorsement of a product, be it motor oil or an eponymously named beverage, ensured its success. Palmer’s enduring marketability brought him wealth far beyond that of any player preceding him. According to a Forbes magazine article some years ago, Palmer earned an estimated $875 million in endorsements, appearances, licensing agreements and golf course design fees. And golf prospered with him.

Timing was a factor. The televising of golf was gathering steam just as Palmer arrived. Blessed with loads of charisma, Arnold’s good looks, blue collar background and go-for-broke approach exuded a telegenic presence that appealed to men and women alike.

Thrilling come-from-behind triumphs in two 1960 majors, the Masters and U.S. Open, enhanced his mystique. The “charge” to victory at Cherry Hills Country Club was particularly sensational. Palmer lagged seven strokes back after 54 holes. Prior to the final round, sportswriter-confidant Bob Drum (later a Pinehurst resident) told Arnie he had no chance, that he was “out of it.” Defiantly, an enflamed Palmer drove the green on the opening hole, and with a deluge of early birdies, mounted a historic comeback to capture his only National Open.

Even before this triumph, his ever-expanding legion of adoring followers was mustering to form “Arnie’s Army.” Whether he won or lost, his troops whooped, hollered and cheered Palmer whenever he hitched his pants or tilted his head. And they never stopped.

Doc Giffin, Arnold’s longtime friend and personal assistant, succinctly explained Palmer’s magnetic appeal. “Arnold liked people, and people liked him because they knew he liked them.” His broad smile when photographed with fans was genuine; he never rejected an autograph request, painstakingly signing with a crystal-clear signature. “No shortcuts, no scribbling,” Palmer admonished many a fellow professional. “Look everyone in the eye and take the time to thank them.” This fastidiousness extended to fan mail, which he never threw away. With Doc’s assistance, the appreciative Palmer answered every letter.

Palmer was the King, but no life is without its hardships. In 1997, then 68, Palmer was diagnosed with prostate cancer. On the same day in 1998 that he received a final dose of radiation, he learned that Winnie, his wife of 45 years, had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. He would call it the worst day of his life. Winnie died in 1999.

By the time Palmer played in the 2004 Masters tournament — his 50th appearance — he grudgingly acknowledged it was time to start saying goodbye. “I’m through. I’ve had it. I’m done, cooked, washed up, finished, whatever you want to say,” he said. “It’s time.” It would be his final appearance in a regular Tour event.

Palmer was not, however, the sort to do nothing. He spent considerable time and treasure in the fight against cancer, funding hospital facilities in Pennsylvania and Orlando, Florida. He thrust himself into his multifarious business ventures with renewed vigor, attending engagements throughout the country. To reach far-flung destinations, Palmer, an accomplished and passionate aviator, piloted his own plane — a Cessna Citation X.

And he still played frequently, almost daily, at Orlando’s Bay Hill Golf Club, rounds featuring good-natured teasing between the King and his playing partners. Most importantly, he found a new love, Californian Kathleen “Kit” Gawthorp. Winnie and Arnold had become friends with Kit and her first husband, Al Gawthorp Jr., when Arnold competed in tournaments at Pebble Beach. Palmer and Gawthorp would later become involved in Pebble’s ownership group. Kit and her husband would subsequently divorce, and following Winnie’s death, Arnold and Kit began seeing one another. The couple announced their engagement on Oct. 16, 2003.

“Kit loves to watch sports, she loves to be at home, and I think that’s really what my dad needs,” observed Arnold’s daughter Amy Saunders. “I think he needed someone who enjoys the things he enjoys, and I think that everybody embraced Kit.”

During Kit’s visit to Latrobe in early May 2004, Arnold suggested they fly south to Pinehurst for an overnight sojourn. Palmer revered Pinehurst and wanted to show it off. Spur-of-the-moment travel was not unusual for them. With co-pilot Pete Luster manning the right seat, Palmer could fly his Citation X to the Moore County Airport in just over an hour.

For arrangements at the Pinehurst end, Arnold turned to his jack-of-all-trades assistant Giffin. The former Pittsburgh Press writer and press secretary of the PGA Tour started working for Palmer in 1966 and would continue to do so until Palmer’s death in 2016. Described in Kingdom magazine (a Palmer enterprise), Doc’s wide-ranging responsibilities included dealing “with everyone: writers, broadcasters, paupers, pretenders, potentates and presidents, including Eisenhower, Clinton and George W. Bush, to name three.” When in Latrobe, the two men typically gathered around 5 p.m. at Palmer’s home for what Giffin puckishly referred to as a “debriefing” — the mutual imbibing of a cocktail or two.

Doc knew the person to call in Pinehurst was Stephen Boyd, the resort’s manager of media relations and special services. Boyd joined the resort’s employ in the mid-1990s, after departing a similar position with American Airlines. Giffin asked him if he could arrange to have Arnold and his fiancée met at the airport, and if he could make hotel and dining reservations for the couple.

“Of course,” replied Boyd. “When are they coming?”

“Tomorrow,” Doc said.

This was no problem for Boyd, who was used to last-minute requests. He asked which hotel the couple would prefer while in town and whether or not they wanted to play golf.

“I’ll let Arnold answer those questions.” Doc said. “He’s right here. I’ll put him on.”

Palmer told Boyd he had no intention of playing golf. “Arnold said he’d like to take Kit on a tour of Pinehurst,” recalls Boyd. “He wanted to share with her the things he had experienced here that meant so much to him.” He wanted to stay in the Manor Inn, a choice that surprised Boyd. At the time, the hotel was rather threadbare, lagging well behind the Carolina Hotel and the Holly Inn in the resort’s lodging offerings.

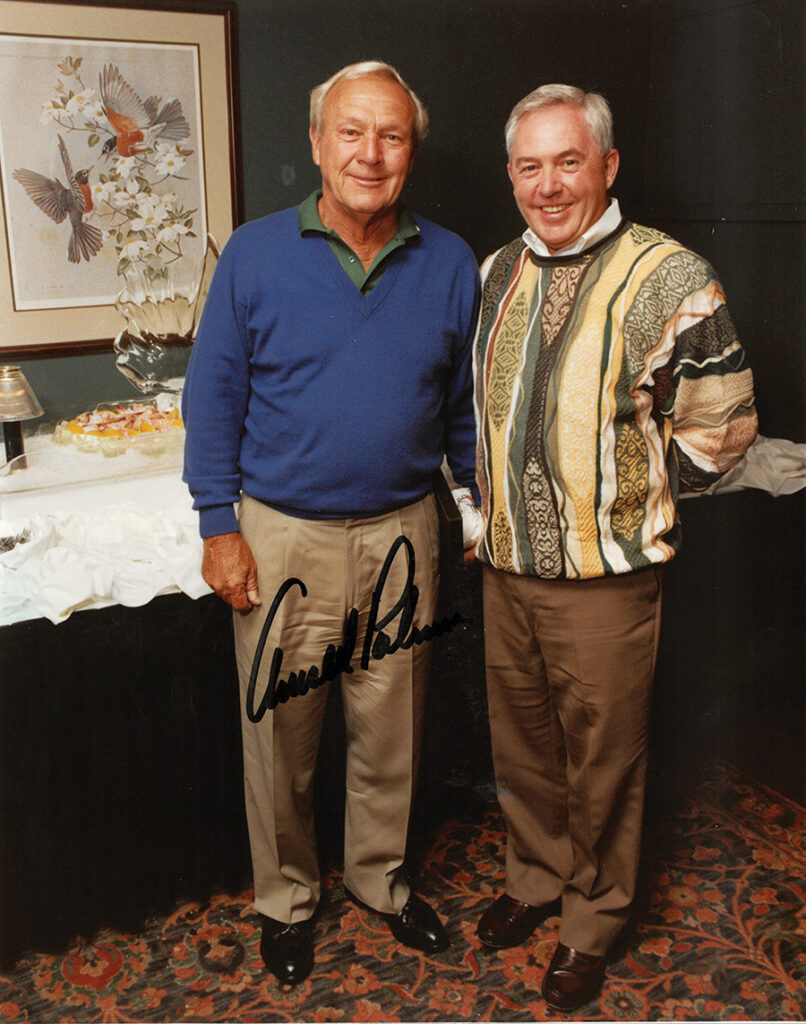

Arnold Palmer and Harvie Ward (Photograph courtesy of Tufts Archives)

(Photograph courtesy of Stephen Boyd)

Palmer had a sentimental reason for his selection. The Manor was where he, his father, Milfred “Deke” Palmer and his dad’s buddies bunked on their golf vacations in Pinehurst during the 1940s and early ’50s. Those visits became a lifelong source of fond memories for the King.

The first occurred when Palmer was 18, and he was immediately smitten. “I loved Pinehurst. I thought it was the most beautiful place I’d ever seen. It was heaven, really,” said Palmer. Pinehurst’s No. 2 course bowled him over, too. It was “the best golf course I had ever played,” he said. “And this was in December, and it snowed about 6 inches. We had to go home because it was snowing so heavily.”

When Bud Worsham, Arnold’s close friend from junior golf, urged his buddy to consider joining him on Wake Forest University’s golf team, the young Palmer was all ears. Worsham persuaded Wake’s athletic director to grant Palmer a full scholarship, employing the clinching argument “Arnold’s better than me!” The two would transform Wake’s golf team into a national powerhouse, with Palmer carrying off two NCAA individual titles.

With Pinehurst little more than an hour’s drive away, team excursions to play No. 2 were frequent. Arnold won his conference’s individual championship on the storied Donald Ross layout, though he was less fortunate in the annual North and South Amateur, where his best finish was a 5 and 4 semifinal loss to a UNC star named Harvie Ward.

When Worsham was killed in a car accident in October 1950, the devastated Palmer dropped out of school and joined the Coast Guard. Following a three-year stint, he returned to Wake Forest for an additional year. After leaving college for good, Palmer won the 1954 U.S. Amateur, turned pro later that year, and joined the PGA Tour.

The tour did not hold events in Pinehurst during the first 17 years of Palmer’s professional career but, when it returned to the resort in 1973, Palmer was invariably in the field. And, in September 1974, he was inducted into the new World Golf Hall of Fame in a ceremony behind No. 2’s fourth green.

Thirty years later, Palmer and his fiancée weren’t coming to Pinehurst for a ceremony — they just wanted to experience the town’s unique atmosphere. Boyd selected a suitable room at the Manor and ordered it stocked with Ketel One vodka and Rolling Rock beer, both Palmer’s favorites.

The next day Arnold, Kit and co-pilot Luster took off for the Moore County Airport. Kit relished flying with Arnold in the Citation X, even toying with the idea of obtaining a pilot’s license herself. She recalled a moment during one of their early flights together when Palmer pointed out the curvature of the Earth. “That was so neat,” Kit said. “The sun was setting, and it created a mystical picture.”

Boyd already enjoyed a favorable impression of the man. In 1994, while at American Airlines, Boyd was invited by Pinehurst CEO Pat Corso to attend a match between Palmer and Jack Nicklaus on course No. 2 for Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf. On the evening prior to the match, Boyd attended a reception where he marveled at how Palmer painstakingly greeted and chatted with each guest as if there was nothing he would rather do and no place he would rather be.

After Palmer’s Cessna touched down at Moore County Airport around 1 p.m., as they exited the plane, he asked Kit to take a picture of him posing with Boyd. Giffin had arranged for Palmer to have a Cadillac available (another Palmer endorsement) on the airport tarmac. “My car was in the airport parking lot,” says Boyd. “I told Arnold what I was driving, and that he should just follow me into Pinehurst.” But Palmer had other ideas. “Stephen, you get in with us and sit up with me. You can show us around,” directed the King.

As the luggage came off the plane, Boyd saw a set of golf clubs. “Mr. Palmer,” he said, “I thought you weren’t going to be playing golf on this trip.”

“I’m not,” replied Palmer with a broad smile, “but you don’t come to Pinehurst without your clubs.”

After first checking on the precarious state of the Carolina Golf Club, located near the airport, a course he had designed with associate Ed Seay in 1997, Palmer turned the Cadillac in the direction of Pinehurst and asked Boyd to provide an impromptu tour for Kit’s benefit. “I talked about the Tufts family, Frederick Law Olmsted, and the history of the village,” says Boyd. “I pointed out homes belonging to Annie Oakley, the Fownes family, Admiral Zumwalt, and others — just a quick historic overview.”

Palmer pulled up to the front door of the Manor by 2 p.m. He asked Boyd for a recommendation on a place to have a glass of wine. Stephen suggested the Pine Crest Inn, just a 200-yard walk from the Manor. “Of course,” responded the pleased Palmer, remembering the establishment. “That’ll be perfect.”

It was early in the afternoon, and the Pine Crest was empty of patrons except for Arnold and Kit, who sat at the bar. Andy Hofmann, wife of proprietor Bob Barrett, remembers their visit. The three chatted for a bit before Andy asked how Ed Seay was doing, knowing he was having health issues. Seay, Arnold’s course architecture partner, had stayed at the Pine Crest while designing Pinehurst Plantation, now Mid-South Country Club. The beefy former Marine had become a popular presence. Rather than answering Hofmann directly, Arnold looked to Kit to respond. “She shook her head,” says Andy. “I already knew Ed had cancer.”

Palmer took note of three stools at the bar displaying name tags of three renowned golf writers who had been entrenched regulars at the Pine Crest: Bob Drum, Dick Taylor and Charley Price. Palmer picked up his cellphone and called Giffin to inform him he was at the Pine Crest bar, sitting with Drum, Price and Taylor. “Doc knows those guys are long gone, and he thought I’d lost my mind,” Palmer told Boyd.

It was a beautiful spring day, and Boyd had arranged for the couple to have dinner around 5:30 p.m. on the outdoor patio at the Holly Inn. The Holly didn’t accept dining reservations on the patio — not even for a king — so Boyd stood in line for a table.

“I was watching for Arnold and Kit, who I assumed would walk up the hill from the Manor,” says Boyd. He caught sight of them right at 5:30, holding hands, as they rounded the corner of Cherokee Road with Palmer sporting his customary look — loafers without socks and a cashmere sweater, loosely tied around his neck.

Once the couple was seated, Boyd told them to have a wonderful evening and began stepping away. “Sit down!” Palmer ordered. “Have dinner with us.” Boyd stayed, but only for a drink.

Corso and his wife, Judy, happened to be dining on the patio that night as well. “What was remarkable is that everyone knew it was him, but no one chose to disturb them,” says Corso. Following dinner the couple continued their sightseeing. Among the stops was Taylortown, home of the resort’s African American caddies, several of whom — including the legendary Willie McRae — had carried Palmer’s bag over the decades.

Boyd joined them for breakfast the following morning at the Carolina Hotel, and afterward, the three sauntered slowly down the halls off the hotel lobby. Palmer inspected the historic photographs hanging on the walls as if they were treasured Rembrandts. Near the Cardinal Ballroom, one photo in particular caught his attention. “Come here, Kit,” he said. “That’s the guy.” He pointed to a picture of Arthur Lacey, the official involved in the most controversial rules dispute of Palmer’s career.

Lacey had been the captain for the Great Britain and Ireland side in the 1951 Ryder Cup at Pinehurst and became a resident of the village after marrying a local woman he met during the matches. In the 1958 Masters, he was the rules official at the 12th green when Palmer’s ball became partially imbedded. Lacey denied Palmer relief. Annoyed, Palmer made a double bogey with that ball but also played a second ball with which he made a par. Tournament chairman Bobby Jones overruled Lacey, concluding that the score on Arnold’s second ball was the one that should count. Jones’ ruling proved crucial to Palmer winning his first Masters. Nevertheless, debate swirled for decades.

On the patio of the Holly the evening before, Boyd had mentioned to Palmer that his old friend Harvie Ward was a Pinehurst resident. Not only had Ward been a golfing rival, he’d dated Winnie before she and Arnold married in 1955. Boyd passed along Ward’s contact information and Palmer did, indeed, reach out, visiting Ward at his home on Blue Road. It would be their final meeting. Ward died four months later.

After he and Kit left Pinehurst, Palmer sent a message to Boyd, telling him their visit “brought back a lot of old memories for me and reminded me how much Pinehurst has always meant to the Palmer family.”

Three months later, at the U.S. Senior Open at Bellerive Country Club in St. Louis, Boyd was assisting in the media center. The USGA assigned him to accompany Palmer’s group, keeping photographers at a proper distance and otherwise making sure that the King could get from point A to point B without too much difficulty.

It was uncomfortably warm in St. Louis, and the 74-year-old-Palmer and his aching back felt the heat’s effects. At one point, he began veering off to the right of center. Boyd asked him if he was OK. Palmer assured him everything was fine. He’d spotted an old friend in the gallery and wanted to say hello. That old friend was baseball great Stan Musial.

Palmer’s trips to Pinehurst weren’t at an end after 2004, and every time he visited, Boyd was his man on the ground. On one trip, at Boyd’s request, Palmer recorded a video expressing his heartfelt feelings about the No. 2 course. When the King returned to Pinehurst in June 2007, for his induction into the North Carolina Golf Hall of Fame, Boyd’s connection with him deepened further. Palmer’s thank-you message was profuse in its praise. “Thanks for all you did from touchdown to takeoff for Doc, Pete (co-pilot Lustek), and me,” he wrote.

“Arnold went out of his way to make me his friend, not just someone who met him at the airport,” says Boyd. “For that I will always be grateful.”

Before passing away in 2016, Palmer made one final pilgrimage to Pinehurst during the 2014 U.S. Open. Reiterating his affection for the town and No. 2, he vowed, “I’m going to come back and play it again before I give up the game.”

The King would have if he could have. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.